The Ordinary Weather (Part 1)

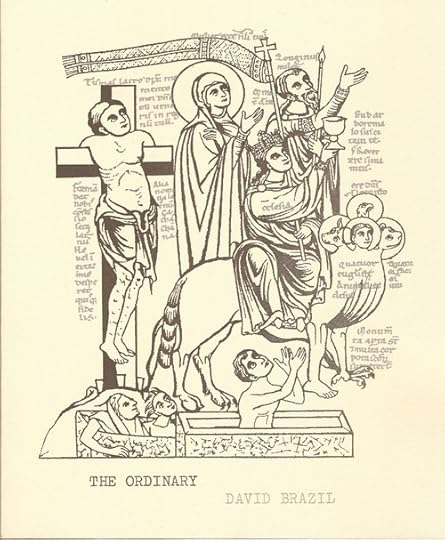

I’ll be periodically posting pieces of the following. If you haven’t picked up a copy of David Brazil’s The Ordinary, it’s available here.

- - -

It’s three months since my father and grandmother died in a tornado, and I’m reading David Brazil’s The Ordinary. That formulation—it’s three mo.’s since and—has become the implicit qualifier of every sentence now, so that, with even the most banal things, the entire life is tempered by that fact, which precedes even pleasure, as debris (now I think) must precede all form. Dad was a junker and, if he’d liked books of poems, I think he’d have liked David’s book, the material conditions of which might be called a heuristics of junking, typified in the central poem here, “Economy.” I want to talk about both—this loss and this book—I want to hold my grief up alongside my reading, because of (if nothing else) the sheer unwieldiness of it, the profanity of pleasure (reading itself, even) in the wake of that loss. I sense a growing impatience in me with the dailinesses, like poems, that would before have passed the time—a petulance in the face of days, a test of each thing down to the last minutae against the heft of grief. So there’s an unreasonableness in my reading that I hope David will forgive me for, that I can’t quite mute.

9-8-13 - In a dream two nights ago, Brazil’s and my friend and publisher, Michael Cross, and Thom Donovan had come to visit Julia and me in Texas. I was walking with the two of them down some farm road when a cluster of funnel clouds formed over a house in the distance. When they touched down they looked like arms, a torso, head and all, and they ripped at the house while we watched unharmed. Later on in the dream, I missed our flight to some very important reading.

In real life the storm had in fact been that precise: it landed on my grandmother’s house where she was with my parents, but their house, just across the driveway, survived mostly unharmed, while all it left of the first house was porches. They could have survived had they happened to be in any of the cars or in the other house when it hit. And they couldn’t have known this. Fucking arbitrariness of the event, precise, but arbitrary.

7-28-13 – Reading “Kairos” - In the first section of David’s book, “Kairos,” the poem’s instance is roughly a month’s time: each poem is dated, about a poem per day. I understand Kairos to mean, roughly, both ‘event’ and ‘weather.’ But the poem’s a facsimile of the draft of the poem, so here event is blurred. There’s an ‘after’ that—notes, strikethrough’s, packing tape piecing together the worked-over sections, etc. The time of after-the-poem’s-time, after the event. My model here is Ponge’s Making of the Pre, and I know I spoke to David about this when I published a chapbook of part of “Economy.” But I know that eventually the whole book’s a question (for me) of “Am I doing the right things with my time?” (CIII).

So, reading “Kairos,” I want to posit another way to ask that question: What’s the weather?

What’s the weather when it marks our time?

And I like an allowance for Hiesenberg, so I remember his formulation, “nature as exposed to our method of questioning,” and immediately qualify:

What’s (our relation to) the weather?

Am I doing the right things in relation to what I understand as the weather?

: & if I read past the evidence of drafting, if I ignore it and attempt to read some ‘final’ form of the poem, as incident, then what?

: & if I stand back to survey the ‘whole’ work (as a picture of work, of time, of weather)—am I doing the right things in my reading?

: & if I attempt to reconstruct (silly?)—to read all the debris of the event, put them back in place, even, in some kind of relief effort?

(At the debris site the relief workers spent weeks sifting through the wreckage, climbing through brush and digging in the mud to retrieve anything they thought might be significant. We loved them for this, but what it looked like, at the end of the day, was someone approaching you with a frisbee full of pocket change they’d found with a metal detector (this is literally what it looked like). My dad would have, had he survived able-bodied, been right there alongside them—The Man on the Dump—because he’d spent his life collecting the remnants of life (from estate sales, storage wars) and never selling them, hanging onto them for what we often wondered. He’d read all the debris.)

I don’t draw this relation because it’s acceptable, as metaphor, but because I feel myself at a loss, after loss, to read otherwise than to give in to a preoccupation of grief. So I don’t mean to craft some theory of the storm of writing or reading, the disaster of it, but maybe to test it by holding it up next to the world, to real weather. A test, maybe, of whether there is in the debris of this writing a knowledge of that other debris, and of the impossible nature of the question of “right things” (when I wonder about reading and writing in the first place now, as right things).

Can’t not ask, can’t answer: What’s the weather as exposed to our method of questioning? This is not a problem of the mediated, but of the irremediable (i.e. the answer won’t change anything).

8-4-13 – Irremediable: distracted, preoccupied nature of reading (even before this). Cf. Blanchot on reader as greatest threat to reading: can’t be read as a doctrine or corrective b/c can’t not be true. Reading is always preoccupied. Even an ascetic practice begins with a world from which to withdraw, an unclear head.

C.J. Martin's Blog

- C.J. Martin's profile

- 11 followers