They can count, too

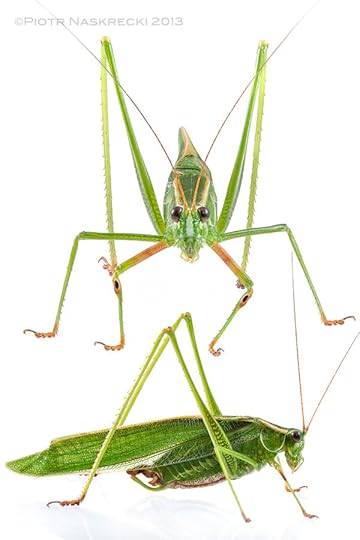

A male Treetop bush katydid (S. fasciata) from Woburn, MA.

In March of 1882 a little known journal that had been founded only two years prior was about to go under – nobody wanted to read it, and its owner was tired of putting any more money into it. But an enthusiastic entomologist named Samuel H. Scudder, who at that time, after many years of doing various unpaid jobs, was finally holding the prestigious position of an Assistant Librarian at Harvard University, had recognized the potential of that publication and decided to save it. He edited the journal until 1886, ensuring that it would gain prominence and a much greater readership. Thanks to his enthusiasm the journal had survived, and later became somewhat influential in the academic circles.

But in addition to his penchant for saving obscure publications from oblivion, Scudder was one of the most prolific and influential American zoologists. His list of papers and books includes 791 titles (!), and many of them deal with my favorite group, the Orthoptera. Because of his contribution to the taxonomy of orthopterans, 24 species of grasshoppers and katydids carry his name (scudderi), as does one genus, the elegant Scudderia, also known as the Bush katydid.

A female Fork-tailed bush katydid (S. furcata) ovipositing between the two layers of a leaf’s epidermis.

I always knew that one species of Scudderia was common in my backyard, the Fork-tailed katydid (S. furcata), and its short, high-pitched clicking calls can be heard almost every night from the deck of the house. But a few nights ago I noticed a different call coming from the garden, and was pleased to find a new neighbor – the Treetop bush katydid (S. fasciata). Bush katydids are graceful, delicate creatures that feed on leaves and flowers of a variety of plants, and in our garden they seem to be particularly fond of bee balm flowers and a few other ornamentals. They spend their entire lives either high in the canopy or in tall bushes, and never descend to the ground. Female bush katydids lay eggs on the vegetation, but do it in a truly masterful way. Rather than laying eggs on the surface of leaves or bark, which many arboreal katydids do, they perform the almost impossible feat of splitting the leaf in two – along its thin edge! – and insert the eggs between the two layers of the epidermis. Obviously, in order to fit there, the eggs must be really thin, and in fact they are so thin as to be virtually translucent when they are initially deposited. They harden and darken as they age, but remain remarkably two-dimensional. Well hidden inside the leaf’s tissue, eggs of Scudderia are probably at a much lower risk from parasitoid wasps, which often wipe out most of katydid egg clutches.

[image error]

The counting katydid, Scudderia pistillata – males of this species add one syllable to each subsequent “click”, and the male with the highest number of syllables has the highest chance of attracting a female. This individual is from Sanbornville, NH.

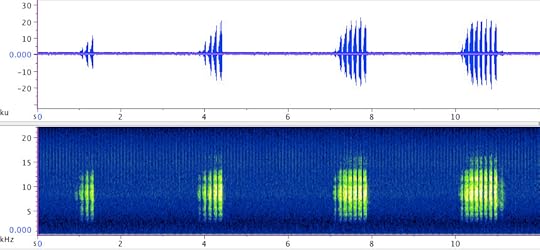

Bush katydids have also one very interesting feature – they apparently can count. Males of the Broad-winged bush katydid (S. pistillata) produce several types of call, but only one is designed to attract females. It usually starts with a typical single phrase, with only a few syllables (to the human ear these sound like a slow “chirp”), but each subsequent phrase adds one more syllable. It has been shown that females preferentially mate with males who produce the highest number syllables at the end of a calling bout. This is probably because longer phrases require more energy to produce, and thus are an honest indication of the male’s health and the ability to invest in his offspring.

Bush katydids are hardy creatures, and I sometimes find them well into late October. Their pretty nymphs are also some of the first katydids to appear in the late spring. They can be identified by their color patter, which often has vivid emerald and orange accents, and by the presence of a small “cone” on the top of their head (this “cone” disappears in adult katydids).

This is how it’s done: the female first chews off the edge of the leaf, and then uses her mouthparts to carefully guide her ovipositor in between the two layers of the epidermis.

Not surprisingly, the beautiful Scudderia is one of my favorite genera of North American katydids, and its members are deserving bearers of the name of one of America’s greatest naturalists. Oh, and the journal that Samuel Scudder saved from oblivion? It was Science.

[image error]

Nymphs of Scudderia can be recognized by their bright, emerald green coloration and the presence of a small “cone” on the head.

The song of S. pistillata – notice how the number of syllables increases in each subsequent phrase. Click here to hear it. (Based on a recording from the Singing Insects of North America.)

Filed under: Behavior, Katydids

Piotr Naskrecki's Blog

- Piotr Naskrecki's profile

- 9 followers