Take the hype out of Hyperloop

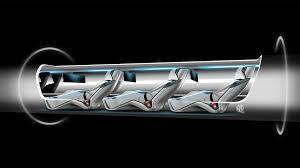

The Hyperloop

It amazes me to read the reactions to the recent proposal by Elon Musk to create a hyperloop – essentially a vacuum tube running from San Francisco to LA, and maybe later one running across the country. Choruses of “it can’t be done” resonate across the media with deafening unanimity.

I ask the question “why can’t it be done?”

I don’t mean why in terms of “how many curves does the track need,” or “what are the issues regarding heat buildup?” for those are the technicalities of innovation that human beings are very good at resolving.

My concern is, why can’t it be done by a nation that was founded on “can-do?” Why do people and the media leap on a good idea and pillory it in the town square?

I think always about Google Earth and Google Street View: The enormous effort of not only indexing the streets and neighborhoods of much of the world, but also actually photographing them in person, and then stitching all the photographs together, and then making them searchable and findable, and then making the results visible on any type of computer for free, and then making it available all over again in 3D. Imagine if any one of our many layers of government had tried to undertake such a project. It would have been buried under mountains of feasibility studies, consultants, diverted funds, earmarked bills, protests, obstruction, cost overruns, strikes, incompatibilities, defects, incompetence and graft. Yet a single company undertook to do this. And they went out and did it. And they succeeded. On their own dime.

The future has always belonged to pioneers and visionaries. Sir Richard Branson named his company Virgin because he went into businesses where he had no experience. He just went and did it. Sometimes he failed. Other times he succeeded enormously. More humbly, but equally significant, the inventor of the 3M Post-It note worked, on company time, to noodle with an idea that was an original project failure: a glue that wouldn’t stick.

Invention comes from experimentation. Innovation comes from drive and vision. Naysayers stand on the sidelines and laugh, yet they’re always ready to come to the party once success has been attained. How many of the people that we observe daily, texting messages to their coworkers or family members, would have greeted with a shudder of revulsion the prospect of carrying a mobile device containing a camera, that can be tracked by big business and government through a series of relay towers? Yet there they are.

The vision of Elon Musk is akin to the works of John F. Kennedy, when he challenged America to put a human on the moon by the end of the decade. It is akin to the ideas of Steve Jobs, or of Nobutoshi Kihara, the Japanese inventor who had the audacity to put a music player (the Sony Walkman) into a person’s pocket. With PayPal, Elon Musk changed the way people do business and transfer money. Mark Zuckerberg changed the way people relate to each other. Did these people ask for permission to do this? No. Did they ask whether it could or should be done? No, they just went ahead and did it.

The great value of Musk’s Hyperloop vision is it gets people talking. In this age of open source idea-sharing, someone else will come along and raise his idea to a new level. The ultimate hyperloop transport may look and operate nothing like Musk’s current vision, the same way a passenger jet has little resemblance to the Wright Brother’s flying machine.

What is sad is that the number of vocal nasayers seems to be greater than the number of enthusiasts. Too many people are more interested in protecting the status quo, where their vested interests currently lie, than to explore new options, which may have great and lucrative ramifications in the near future.

A company can only ever be moving forward or moving backward. You advance or you die. This notion applies to countries and civilizations also. When resistance to innovation overpowers personal motivation, the nation dies. And other hungrier nations leap in to fill the void.

I for one would like to see the media, and its corporate masters refrain from their soft mockery of visionary inventors, scientists and geeks, and instead question where the world (or at least their corner of it) will be in 50 years if these people are not given the credibility that they deserve. Because the status quo is not in a rock-solid state. It it like glass – a liquid that drips slowly down by the inexorable pull of gravity and of reality.