POSTERITY

While doing research for writing western historical novels I often read memoirs or autobiographies of the period. Not only are they informative but they also set the tone and bring me back in time. Yet they pose a query in my mind. Why were they written? What possesses someone to write a memoir or an autobiography, to tell their story? Has someone asked them to, as seems to be the case in Teddy Blue Abbott’s We Pointed Them North’? Is it a need to share their experiences and a belief that others may profit from knowing their life story? Is it an arrogant nature that believes everyone will be interested in what they have to say? No more, I should think, than what is written from any other author. Perhaps they are working through something, cleansing their mind? Or is it just putting down one’s life for posterity? Clearing their name, setting the record straight, laying down for posterity exactly who they were and what happened?

While doing research for writing western historical novels I often read memoirs or autobiographies of the period. Not only are they informative but they also set the tone and bring me back in time. Yet they pose a query in my mind. Why were they written? What possesses someone to write a memoir or an autobiography, to tell their story? Has someone asked them to, as seems to be the case in Teddy Blue Abbott’s We Pointed Them North’? Is it a need to share their experiences and a belief that others may profit from knowing their life story? Is it an arrogant nature that believes everyone will be interested in what they have to say? No more, I should think, than what is written from any other author. Perhaps they are working through something, cleansing their mind? Or is it just putting down one’s life for posterity? Clearing their name, setting the record straight, laying down for posterity exactly who they were and what happened?

Before anyone out there points out that my last months’ diary was a memoir, I’m well aware of that. I’m not analyzing why I filled empty white pages with a diary, nor do I want to go into the psychobabble of some people’s needs to work out their problems through writing. Who we are comes out in our writing no matter what we write. Whatever story we tell, that story is a part of us. But some people do write for a specific purpose. They write for posterity.

Helen Huntington Smith starts her preface to We Pointed Them North, which she co-wrote with Abbott, by saying, “This is a book of reminiscences by an old-time cowboy…” and “With the idea in mind of preserving a record, I have kept close to Mr. Abbott’s exact words.”(italics mine) Mr. Abbott was doing nothing more than recollecting his life story, which Ms. Huntington Smith was taking down, much as one might retell parts of your life to grandchildren. Since Ms. Huntington Smith had approached Abbott on another matter, it would be difficult to argue that the ‘old-time cowboy’ had any ulterior motives to having his story published—other than, understandably perhaps, financial.

Whether or not there were pure monetary reasons behind Pat Garrett’s The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid is, however, arguable. He certainly didn’t make much money from the book during his lifetime, and it wasn’t until reprints in the 1950s that it reached a wider audience. Garrett tells The Kid’s life story in order to build up to his part in The Kid’s death. In 1882, laying claim to having killed the most notorious outlaw of the day would certainly gain you both admiration and publicity, and Garrett does seem to manipulate the reader towards his own end. While he states openly that he is “incited to this labor…by an impulse to correct the thousand false statements which have appeared….” he certainly makes an attempt to stack the cards in his favor; an unbiased account this ain’t. First he builds up The Kid as a decent young man—even a ‘mama’s boy’—who goes wrong, so that it gives the reader the impression of being fair. Yet on the other hand, he makes no restraints on using language meant to inform the public of what a monster The Kid turned out to be. Phrases such as “Deeds of Daring and Blood, His name a Terror” would certainly make the average reader believe we were well rid of Billy the Kid, and the man who shot him was just short of sainthood. Furthermore, expressions such as “A faithful and interesting narrative” or “verified history of The Kid’s exploits” lend veracity to the text. As my colleague Paul Colt pointed out to me, “…it is the ‘Authentic’ life of Billy The Kid as opposed to what other life of Billy the Kid? The nineteenth century printed word had the cachet of fact. It clearly worked for Garrett.”

Colt visited the question of whether Garrett actually killed The Kid in an earlier post on this site, Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett — The Shadow of Doubt. Basically, in a memoir he published in 1933 titled The Death of Billy The Kid, Garrett’s deputy, John Poe, has disputed the sheriff’s claim of having killed The Kid. It’s interesting that he would have waited over forty years to debate Garrett’s assertion. But did Garrett foresee this argument? Was this book his testament to his own life, to what he saw as his one great accomplishment? It certainly doesn’t appear that, like Teddy Blue Abbott, he might have been writing for the grandkids.

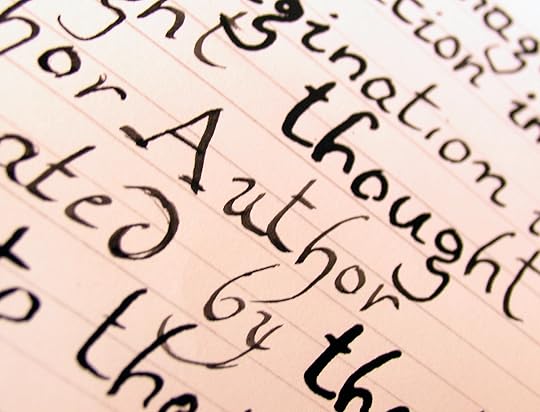

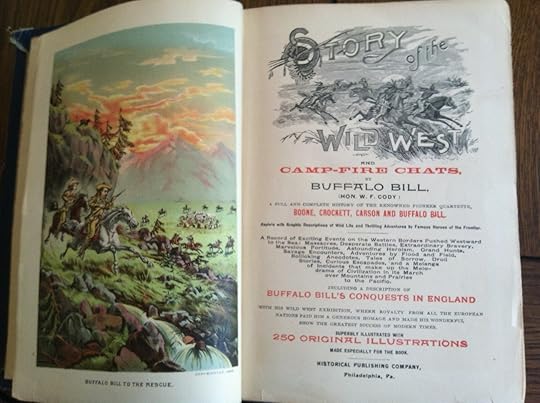

Manipulative language also plays a part in  William F. Cody’s The Story of the Wild West and Campfire Chats, published in 1888. Cody’s story of the Wild West is basically his own autobiography along with three shorter biographies of Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and Kit Carson. Still only forty-three years old when he wrote the book, the title alone might prompt the reader to accuse Cody of hubris. His authoritative position is further enhanced by the use of ‘The Hon. William F. Cody,’ a title he was barely entitled to after being Justice of the Peace for a mere two months. In addition, the use of the rank of Col. towards the end of the book is pure invention; Cody was a scout in the Army although he did serve briefly during the Civil War, but he certainly never made it to Colonel.

William F. Cody’s The Story of the Wild West and Campfire Chats, published in 1888. Cody’s story of the Wild West is basically his own autobiography along with three shorter biographies of Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and Kit Carson. Still only forty-three years old when he wrote the book, the title alone might prompt the reader to accuse Cody of hubris. His authoritative position is further enhanced by the use of ‘The Hon. William F. Cody,’ a title he was barely entitled to after being Justice of the Peace for a mere two months. In addition, the use of the rank of Col. towards the end of the book is pure invention; Cody was a scout in the Army although he did serve briefly during the Civil War, but he certainly never made it to Colonel.

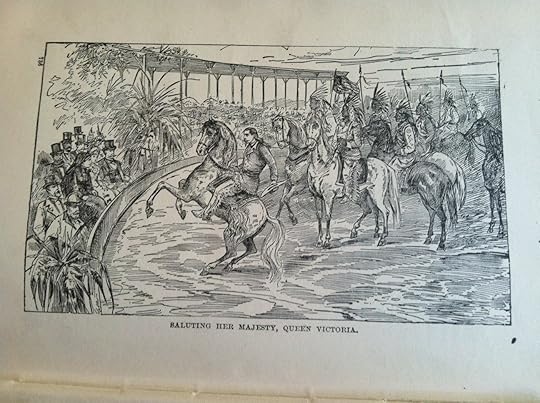

Since the copy by the frontispiece was written to  incite prospective readers to believe that within was the ‘The Full and Complete History of the Renowned Pioneer Quartet’ with “…massacres, desperate battles, extraordinary bravery, marvelous fortitude…’ and so on and so forth including ‘Buffalo Bill’s Conquests in England,’ I was certainly expecting about the most pompous and arrogant memoir ever written. So imagine my surprise when I came upon writing which is almost purely straightforward and unemotive. Not only that, but Cody is capable of admitting to various indiscreet incidences and mistakes he had made in the course of his life, such as encouraging the development of a town called Rome in KS on the basis that the railroad would make it a primary junction. It didn’t; the railway developed Hays instead. In addition, there are delightful moments of the hero’s modesty such as during his first trip east when he declares he had to get used to people recognising him. It was quite apparent that Cody had no part in the cover copy; possibly, he even added the Colonel

incite prospective readers to believe that within was the ‘The Full and Complete History of the Renowned Pioneer Quartet’ with “…massacres, desperate battles, extraordinary bravery, marvelous fortitude…’ and so on and so forth including ‘Buffalo Bill’s Conquests in England,’ I was certainly expecting about the most pompous and arrogant memoir ever written. So imagine my surprise when I came upon writing which is almost purely straightforward and unemotive. Not only that, but Cody is capable of admitting to various indiscreet incidences and mistakes he had made in the course of his life, such as encouraging the development of a town called Rome in KS on the basis that the railroad would make it a primary junction. It didn’t; the railway developed Hays instead. In addition, there are delightful moments of the hero’s modesty such as during his first trip east when he declares he had to get used to people recognising him. It was quite apparent that Cody had no part in the cover copy; possibly, he even added the Colonel  under duress of his publishers. But age forty-three for an autobiography? Even in the 1880s this was rather young.

under duress of his publishers. But age forty-three for an autobiography? Even in the 1880s this was rather young.

Money might well have been one reason. The tour to Europe cannot have been cheap despite the thousands who attended performances. Cody also takes a distinct pride in recounting his adventures and even ends the book with a letter of praise from General W.T. Sherman. And that, for me, summed it up. He was writing for Posterity.

Posterity means different things to different people. Its definition is “future generations.” Yet, unless you are particularly famous, the likelihood of you writing specifically for the knowledge of future generations is not great. So why write an autobiography or a memoir? Is it just a darned good story you’d like to recount or was there some further reason that prompted you to set this specific tale to paper. And were you completely honest in the telling? Or were there things best left unsaid that went untold.

***********************************************************************

Sources:

We Pointed Them North, E.C. “Teddy Blue” Abbott with Helen Huntington Smith, University of OK Press, Norman, 1939

The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid, Pat Garrett, MacMay22, digital, 2009

Story of the Wild West and Campfire Chats, Buffalo Bill (Hon. W. F. Cody), Historical Publishing Co., Philadelphia, Pa., 1888

My thanks to Paul Colt for his input on Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid. Paul’s latest book, Boots and Saddles: A Call to Glory, will be published by Five Star on Dec.18. Paul’s book dealing with Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid, A Question of Bounty, will also be published by Five Star.