Changing the emperor’s name: why do we want to rename some cancers?

Crossposted at .

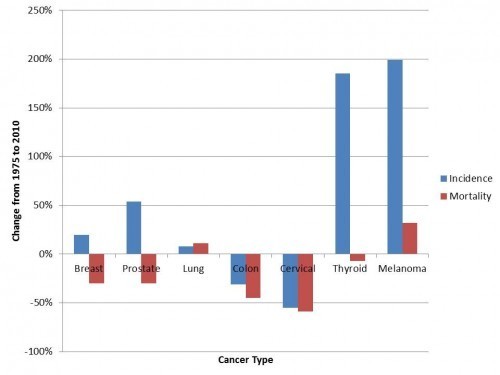

Some types of cancer, as we have known for a while, are overtreated and overdiagnosed. There was a good post at the Well blog on the topic yesterday. For the real skinny on the matter, though, head over to the Incidental Economist, who helpfully classifies cancers into three types: those for which diagnosis (detection) has increased, and mortality decreased – but due to improved treatments, not the screening tests themselves (example: breast cancer); those for which detection has increased, thus catching cancers earlier, decreasing incidence and thus mortality (example: colon cancer) – and, finally, those for which screening has increased the number of “cancers” caught, but with no benefit for mortality, because we’re just pushing the definition of cancer earlier and earlier to catch so-called “cancers” that didn’t need to be caught anyway (example: thyroid cancer).

Cancer incidence and mortality. Courtesy Aaron Carroll and the Incidental Economist.

“So-called”: for some cancers, the emperor of maladies needs to have a name change to something less scary. At least, that’s the thought put forward by some experts in the Times piece. For some cancers, the thought’s been kicked around for a while. (To take another example, the NIH State of the Science report in 2011, on localized prostate cancer, floated the idea of calling low-risk prostate cancer…something else.)

Here’s where science comes in, though, with its persnickety insistence on specifying questions and causalities. What do we think the name cancer is doing, and what are we trying to achieve by renaming low-risk cancers?

Is “cancer,” or the name “cancer”:

increasing anxiety on the part of patients, causing them to expect more invasive treatments?

increasing anxiety on the part of patients, making it more uncomfortable for them to participate in conservative (less invasive) monitoring programs?

increasing anxiety on the part of family members or partners?

Or, perhaps, sensitizing providers to the perceived wishes of patients, real or not, for aggressive treatments?

Similarly, what are we trying to do with changing the name? A cultural change to help decrease overuse? A means to decrease patient anxiety? A signal to providers to adopt different approaches?

We can’t say “all of the above,” because different strategies require different emphases. Let’s design those studies, science-types, and find out what gives! Then perhaps, eventually, the emperor will be a commoner again.