What’s Normal?: Disability and Privilege by Wilfredo Gomez

What’s Normal

?: Disability and Privilege by Wilfredo Gomez | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)

What’s Normal

?: Disability and Privilege by Wilfredo Gomez | special to NewBlackMan (in Exile)What is “normal” and where do we locate and identify “privilege?” The segment on privilege, responsibility, and celebrity airing on the July 21, 2013 episode of the Melissa Harris-Perry show highlighted several forms of privilege in America: heteronormative, male, celebrity, amongst others. A less mentioned form of privilege was raised as a metaphor, or perhaps, better yet, a proxy from which to gauge and situate notions of white privilege. The topic of able-bodied privilege was raised, which while poignant and thought provoking, was somewhat misleading in its representation of what is normal.

The conversation takes its framework from the introductory remarks from Harris-Perry where she humbly notes: …If you look behind you, my cameras probably can’t see it. To get on this stage you have to walk down three stairs. There is no way to get here without walking down three stairs. That means when I think about booking this show, I have never booked someone in a wheelchair to sit at this stage. The reason I can not is because my building is built in a way that makes it impossible for a person dealing with a disability to show up at my table, and that is privilege…

While the Americans with Disabilities Act is a central component to protecting the civil rights of those impacted by disabilities throughout the United States, it is precisely the unfolding of the conversation that normalizes ideas about disability. The fact that MSNBC viewers were not privy to the make-up of the studio does not obscure the fact that mobility issues and questions of access are not the sole experiences or representation of all disabled folk. The issues of access and wheel chair accessibility, however normative they appear in conversation, further blurs the lines as to where culture, socialization, privilege, and presence converge and depart. Harris-Perry is cognizant of the question of accommodation as it pertains to mobility and access. We should not assume that the issue of physical access is the only form of disability. There are people whose presence, bodies, dispositions, and disabilities are not readily visible, to the human eye or the camera. These disabilities are psychological, emotional, cognitive, neurological, and yes, even physical.

I raise this point to allude to the iterations and definitions of degree that shape, mold, and effectively modify, how we read, identify, empathize, and relate to disability—the visible and invisible tolls of disability. Not unlike questions of race, your perceived disability, in part, is about how others around you read your body. However, there is the question of intersecting identities of race, class, sexual orientation, religious affiliation and the like, and how they may or may not trump notions of being able-bodied or disabled in society.

I am a disabled Latino male with cerebral palsy. My limitations, issues of mobility, access, and strength do not overlook the fact that if I were a guest on the show and I were seated amongst the host and other panelists, the viewing audience would not know of my disability unless I acknowledged it on air. My intellectual abilities, educational attainment, and ability to articulate myself, sometimes leads people to question that disability, whether I am seated or standing.

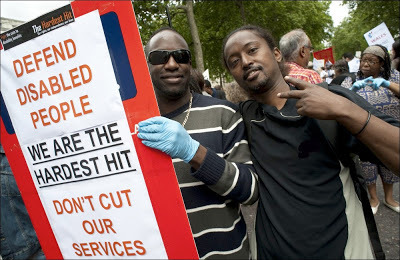

While I am not attempting to speak to a post-disabled America, a notion that disability is somehow masked, less noticeable, or readily ignored due to one’s intellect and independence, I acknowledge that my ability to walk at a rally in support of Trayvon Martin is an act of privilege. I also acknowledge that the ability to walk at said rally will come with its fair share of stares and assumptions about my body. Some of those stares and assumptions may very well come from those marching for justice on behalf of Trayvon. Having to deal with those stares and assumptions is not a manifestation of privilege.

I ask you in light of this, what does it mean to be disabled and embody privilege? What does it mean to belong to multiple minority groups (race and disability) in America? How might the lived realities of my Latinoness and disability inform and complicate one another? What of other experiences that complicates and contradict my own? Where can these conversations be had? And to the extent that a conversation on disability and its critical engagement can frame and augment a discussion of the Zimmerman case, we must be mindful of the ways in which black male bodies are viewed as consummately able, yet far too often perceived and portrayed as physically threatening.

That is to suggest, that the black male body is disabled in its ability to embody, radiate and/or illicit humanity, all the while being seemingly enabled to be a symbolic marker, a martyr, for (in)justice. How do we as a country disable and disarm language to talk about the inherent privileges we assume and take for granted? The fact that I have posed these questions are themselves a manifestation of privilege, so what is normal?

***

Wilfredo Gomez is an independent researcher and scholar who can reached via Twitter at @BazookaGomez84 or via email at gomez.wilfredo@gmail.com

Published on July 29, 2013 13:25

No comments have been added yet.

Mark Anthony Neal's Blog

- Mark Anthony Neal's profile

- 30 followers

Mark Anthony Neal isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.