On Revision: Retrofitting a Spine

Just for discussion purposes, let’s pretend you’re one of those writers who doesn’t start with an outline. Maybe you’re even one of those writers who doesn’t have a plot in mind when s/he starts writing, just begins and hopes that the plot will appear beneath her like a magic carpet.

Eventually, you finish something that might be called a novel. EXCELLENT. Congratulations.

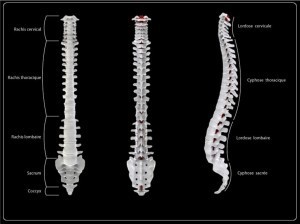

However…. When you read it over — and perhaps this is even after several revisions, and perhaps with the kind editorial comments of a trusted reader or two — you recognize that something is missing. Just to be old-fashioned, let’s call it structure. Bones. Whatever. Yes, you’ve written something moving and lovely and it’s a work you care about. But still. When you look at it, you are reminded of a jellyfish.

In considering jellyfish, you observe that although invertebrates have had lots of success in many ways, they are still to be found mostly in mud or water or living in your food.

Is this what you want for your novel? The existence of a slug or a mollusk or a… sponge?

No. Your novel’s place in the animal kingdom is graceful gazelle or gliding eagle or killer whale. Jaguar, maybe. Even kitten. But not helminth.

Fortunately, having had some experience with this, I’m here to tell you that it’s never too late to give your story a backbone.

What follows is my 12 step program for elevating your novel’s spot in the evolutionary tree.

1. Acknowledge that you are not, in fact, powerless over this problem. That’s right — you are your own higher power.

2. Lay out your entire work in front of you. This could be using pixels on a screen or using paper on a flat surface. (Remember, if you lay it out on a table, you may have to deal with bits dripping off the sides.)

3. Poke it gently in search of the areas of greatest life and responsiveness. Make note of these. Also make note of the areas of LEAST life. Consider making two lists, one titled Working/Compelling/Alive and one titled Not Working/Uninspired/Possibly Dead. (There may, of course, be large chunks that you consider neither dead nor alive.)

4. Identify your plot points. You’ve heard of these, right? Look at your story and pull out as many of these as you can find. Here’s an example from a story you might know.

Little Red Riding Hood (LRRH) is the beloved granddaughter of a woman who lives alone in a cabin in the woods.

LRRH’s grandmother has fallen ill.

LRRH’s mother sends her off to bring some wine and cake to her ill grandmother.

LRRH’s mother warns her of the dangers of the woods and advises her to stick to the path and go right to grandma’s.

Etc.

6. Take your plot points and develop these into a simple outline.

For example:

Opening:

–Intro LRRH and mother

–Ill grandmother, off in the woods alone

–LRRH beloved by everyone, but esp by Grandma

–LRRH’s mother somewhat ambivalent about sending LRRH off by herself – maybe it’s the first time she’s gone alone, maybe the mother is very worried about the grandmother but cannot go herself, etc.

–LRRH’s mother deals with her anxiety by giving LRRH lots of instruction

LRRH sets out:

–Pleased that her mother trusts her to go alone

–fully intending to follow mother’s instructions

ETC.

7. Read through your manuscript. Either by physically/electronically cutting and pasting or by using post-its, highlighters or other favorite tools, assign your text to the appropriate place in the outline. If you have text that doesn’t fit into the outline, leave it out for now.

8. All sections that fit somewhere in the outline and fall into the “Alive” column are staying. These are your first vertebrae. All the sections that don’t fit into the outline and have been categorized as “Dead” are cut.

9. Sections that are “Alive” but don’t fit into the outline should be set aside – you can come back to these later and determine what their function is (e.g. character development, scene-setting vs. just a beautiful bit of prose). Maybe they’ll be a place for them, or maybe there won’t.

10. Read over sections that are “Dead” or otherwise not alive but fit neatly into the outline. What’s missing? Make notes on your outline with ideas about how to fix these. If they seem unfixable, get rid of them and make a note that you’ll have to write new scenes there to keep your plot moving along.

11. Areas where there is a plot point or an important piece of information identified in your outline but no text with it will need to be… written. These are your missing vertebrae.

12. With outline and text in hand, use your own musculoskeletal system to sit yourself down in the chair and get to work.

Any other ideas out there for adding a little bit of spine to a project?

Chris Abouzeid's Blog

- Chris Abouzeid's profile

- 21 followers