The Mysterious and the Not-So-Mysterious

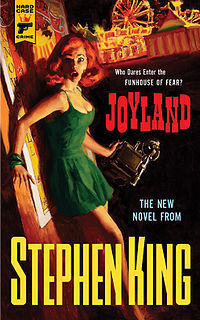

Joyland by Stephen King

I read my first Stephen King novel when I was in the seventh grade: The Wastelands, one of the installments in his Dark Tower series. It was the first book I’d ever read that wasn’t assigned by a teacher, and I tore through it in a matter of days. Sure, the writing was so-so–even as an adolescent I could tell this about King–but there were monsters and death and time warps and guns and explosions and demons, everything a discontented 13-year-old could hope for. To put it simply: it was fucking fun.

I read my first Stephen King novel when I was in the seventh grade: The Wastelands, one of the installments in his Dark Tower series. It was the first book I’d ever read that wasn’t assigned by a teacher, and I tore through it in a matter of days. Sure, the writing was so-so–even as an adolescent I could tell this about King–but there were monsters and death and time warps and guns and explosions and demons, everything a discontented 13-year-old could hope for. To put it simply: it was fucking fun.

Since then, I’ve read maybe two-thirds of King’s catalogue, and while his books and novellas tend to be either amazing (The Green Mile, Rita Hayworth and the Shawshank Redemption) or stomach-wrenchingly terrible (Duma Key, The Girl Who Loved Tom Gordon) with very little grey area, that sense of fun, that at the very least the author is enjoying himself and his craft, is prevalent in all his work.

King continues this playfulness in Joyland, published by Hard Case Crime, a pulp crime throwback outfit created by Charles Ardai and Max Phillips. The company’s roster includes some three dozen or so seasoned writers, most of them with some experience in the crime and thriller genres, and each book cover is illustrated in the pulp tradition, usually featuring some busty femme fatale peering furtively at the viewer. It’s kind of brilliant really, resuscitating such a literary tradition, especially considering how increasingly fractured our attention spans are becoming, as well as the corresponding attention given to on-the-go digital literacies. In this sense, King is a perfect fit for HCC. His contribution here is a jaunty supernatural mystery whose appeal is in its insistence that the reader simply enjoy the ride without taking it too seriously.

The story is told to us by Devin Jones, a college student who, after being shunned by his sorta-girlfriend, takes a job at a shabby North Carolina amusement park called, yes, Joyland. As Devin acclimates to his quirky new environment, all the while pining for the girl (and, consequently, a chance to lose his virginity), King introduces us to the carny world with encyclopedic bravado; it’s easy at times to get distracted by all the terminology he so eagerly throws at us–park-goers are called “rubes,” the Ferris wheel is a “chump-hoister,” etc.–but perhaps this is to be expected from the man Harold Bloom once derided as “an immensely inadequate writer on a sentence-by-sentence, paragraph-by-paragraph, book-by-book basis.” The characters are predictably stock, like Ms. Shoplaw, owner of the boarding house where Devin rents a room, who is conveniently well-versed in the park’s history; or like Lane Hardy, a derby-hatted carny prone to antiquated jive talk reminiscent of Cagney, but nowhere near as cool.

But of course, it all works, albeit in that backwards pulp kind of way. Devin is a likable narrator, and most of the other characters too, partially because our dealings with them are so brief; at 283 pages, Joyland is roughly a quarter the average length of King’s books, meaning that there is much less time for the story’s weaknesses to wear on us. But mostly it’s because they do only what is necessary to move the plot along at a reasonable pace, asking very little of the reader in return. There’s a very practical reassurance here; they aren’t interested in whether or not we like them, only that we keep turning the pages.

As the story continues, we find that there is more to the park than we first expected. Or perhaps we did expect it. Isn’t that the basis for a such a story? Are we surprised to know that a young woman was once murdered by her boyfriend in the Horror House? Does it shock us to know that Fortuna, the Joyland fortune teller, might actually have psychic abilities? And are we at all jolted by the notion that Devin’s friendship with a terminally ill boy and his “foxy” mother could be the key to solving the mystery of the ghost that has allegedly been haunting Joyland?

As the story continues, we find that there is more to the park than we first expected. Or perhaps we did expect it. Isn’t that the basis for a such a story? Are we surprised to know that a young woman was once murdered by her boyfriend in the Horror House? Does it shock us to know that Fortuna, the Joyland fortune teller, might actually have psychic abilities? And are we at all jolted by the notion that Devin’s friendship with a terminally ill boy and his “foxy” mother could be the key to solving the mystery of the ghost that has allegedly been haunting Joyland?

Hardly. That’s what King’s books are all about. And really, that’s sort of what the pulp genre is all about: it’s a chump-hoister in itself, a ride that promises only the fleeting thrill of putting some distance between you and the world for a short period of time. I don’t disagree with Bloom’s contention that Western literature has been increasingly debased, but I find it problematic to assume that “popular” fiction, written for sheer enjoyment, is inherently bad (my guess is that Bloom would cringe should names like Delillo and Roth and Pynchon suddenly start selling by the cartful at Wal-Mart). Fun is a good thing, and reading, I think, at the end of the day should be fun. Joyland is no work of art, but it actively aspires not to be, at least not in the way that folks like Bloom might define it, and by that measure it is immensely successful. Just sit back and enjoy the ride.