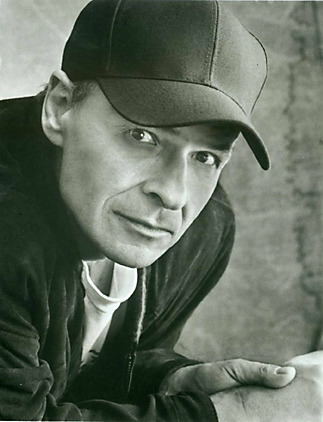

Interview with Tim O’Brien: “It’s the sound of conclusion”

By Sonya Larson

It’s been two decades since Tim O’Brien’s new work of “fictional memoir” was first published, and since then The Things They Carried has risen to an unparalleled classic of Vietnam literature. Few other works have explored the war and its implications so hauntingly—as one soldier’s experience, as a necessity of story-telling, as truth compromised by violence.

The Things They Carried won France’s prestigious Prix du Meilleur Livre Etranger and the Chicago Tribune Heartland Prize; it was also a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Now, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt is re-releasing The Things They Carried on its twentieth anniversary. Beyond the Margins spoke to O’Brien from his Los Angeles hotel room as he tours the country to promote his book once again. He’ll be in Cambridge tonight, March 25th, 7:00pm, at the First Parish Church Meetinghouse, courtesy of Harvard Bookstore.

Congratulations on the re-release of the book [The Things They Carried]. Does it seem like it’s been twenty years since you wrote it?

Thank you. In some ways it does, yes. In other ways, it feels like yesterday. A little combination of both.

Where were you writing it at the time? What were you doing?

I was in Boston. I was living in Cambridge, actually, and I finished the book in Boxford, which is a town outside of Boston.

The form of the book itself broke convention in many ways. Of course it deftly explores the line between fiction and memoir. Were you at all concerned that readers might not understand or dislike what you were doing?

No, I really wasn’t concerned. I thought those who would get it would get it, and those who wouldn’t would be very literal-minded, and probably wouldn’t like any book that has any complication or ambiguity to it. So, I guess I didn’t really worry about that at all. I worried about trying to make the best book I could make.

What came first– the idea for the story, or for the form? Or were they one and the same?

That’s a good question; I’m not sure I have an answer. These things intertwine and overlap, and there was really no point where I made a decision regarding the book’s form. Or anything else, really. It occurred in the course of the writing. Something would happen with a sentence or a paragraph or a plot twist, and it would ring a bell. You tuck those things away as a writer. So the form of a book congealed over the first year or year and a half of writing it. I knew early on that I wanted to write a book that was fiction, full of invention and made-up incidents, but also a book that would feel to readers as if it may well be real, almost as if it had the sound of memoir. I knew that from the beginning. But finding a way of doing it took almost a year and a half of writing it.

At what point did the book start to gel in that way that you envisioned it?

I suppose the crucial chapter was the chapter called “How to Tell a True War Story,” which is at the center of the book. That chapter directly addresses those questions, almost in an essay form. It explores issues of what’s true, degrees of truth, varieties in which truth comes, and how it evolves. What’s true one day may be untrue the next. And that’s life. Someone can say, “I love you” one day and say “I don’t love you” the next, and both days be telling the truth, because the truth has changed.

In a situation that’s so full of uncertainty and ambiguity and horror– such as a war– there’s that feel of fluidity to truth. The old truths, such as “Thou shalt not kill,” become untrue. You’d better kill, or they’ll court-martial you. You have to. It’s patriotic and good to kill. And what one assumes your whole life to be true– that you shouldn’t be doing this stuff—is suddenly sanctioned, and noble, and sublime and all rest. And that can turn your mind upside-down.

What’s true and what’s not true? Questions like that: what’s true about yourself. Are you a good person? You think so. Until a moment at war when something terrible happens and you pull the trigger. You begin to reassess the truth about yourself. And the book as a whole is a kind of investigation of that, and stories revolve around that very issue that you brought up. And that’s what I mean by the form of the book coming out of the about-ness of the stories. And in different ways each of the chapters of the book deals with a facet of this very issue, what we call truth in its elusive and fluid nature.

I’ve always thought that the form works particularly well because the book deals with Vietnam, a war fraught with questions of what is true, and who has authority to confer truth. It’s almost as if the only way to portray that war truthfully is to do so in this form.

I think that’s true. And it’s the same if you go through a bad marriage, or a love affair that’s gone badly, or a childhood with an alcoholic father, no money in the house and absent parents. There are all kinds of ways in which one could write a similar book that would not have been taken place in a setting of war. It’s the same stuff, which in the end comes percolating out. I guess in a situation of crisis very fundamental questions are asked about identity, such as, is there a god? What’s true in this world of ours? Things that had been taken for granted and assumed for so long are suddenly undercut in ways that send you spinning.

I think that’s partly why the book has endured, that it strikes people. It’s not just a story about war. Readers take it very personally in their own lives. I’ve received letters from people with terminal illnesses, for example, who feel as if their absolutes– their bedrock that they had counted on for so long– was then sucked out from under them, who also feel the burden of things they have carried through illness or divorce, their imprisonment or whatever is in their background. But I think that’s part of the book’s longevity. It’s partly a story about what happens to men in a war, but more deeply it touches people to actually look at their own lives and childhoods. The reason that book ends not in the war, but with little Linda dying of brain cancer, is that that chapter is meant to move away from war to the lives of all of us.

Does this book stand out to you as one of your favorites personally?

I wouldn’t say it’s my favorite. I have four or five that I like best in different ways—they’re like children, in a way. I love them in different ways and for different reasons. But I think Cacciato [Going After Cacciato] is just as good a book, I think Tomcat in Love is just as good, and I think In the Lake of the Woods is too. But in the end that’s my opinion. Every author has a group of books that they feel is of equal merit, but that doesn’t mean readers feel that way.

Which story or stories in The Things They Carried means the most to you, or that you believe in the most, if there is one?

Well, again that’s hard. They’re like children—it’s so hard to say. I wouldn’t have left anything in the book—I would have taken it out—if I felt it wasn’t worth the reader’s time to read it, and if my heart wasn’t moved by it. Even the smaller stories that are not much talked about—they’re necessary to the fabric of the book. It wouldn’t feel cohesive without them. It would be like looking at a person’s face, and you’d have the eyes and the mouth, but you wouldn’t have any jaw. The eyes and the mouth would look funny, no matter how beautiful the eyes were. Just a lot of neck, and it would all look very peculiar, like a Cheshire cat. I can’t say I have favorites.

Do you remember a particular story or stories that were left on the cutting room floor, so to speak?

Not chapters or stories. I left paragraphs, sentences. If you were to pick them off the floor and glue them together, they would probably be four or five time longer than the story. But it wasn’t a particular story or a chapter. Or even a scene. What was cut was much of language that wasn’t good enough.

How did you know that the book was finished?

Sort of like a song. You feel a crescendo or finality that’s indisputable. It’s the sound of conclusion. The way you can tell from someone’s voice when they’ve said good-bye for the last time. They’ve said good-bye twelve times before, but you know from the sound of the voice that that good-bye is the final one. And I don’t mean that in a mystical way or a mysterious way; I think there really is a sound of conclusion when one feels that that’s it. And the line that ends The Things They Carried, “trying to save Timmy’s life with a story,” it has the sound of everything that I wanted the reader to feel.

Are you excited about coming to Boston next week? How long did you live here?

I lived there for about twenty years—I lived in Cambridge technically. I’m in L.A. now, midway through the book tour, but I’m really looking forward to coming to Boston. I really feel like I have a home there.

I read that your publisher is re-issuing the book in hardcover and softcover, e-book and Kindle. It’s the greatest effort that’s been put behind a backlisted book since, well, forever, in this new digital age. Is it overwhelming? What’s that like?

It’s really nice. I mean the book has sold so well over the years; it’s read at so many high schools and colleges that I’m not sure of the magnitude [of change] this will make. It’s been there forever and I hope it will stay there. But what’s nice is that the publisher is really going all out—the publisher didn’t have to do this. They could have printed it and sold it and it would have done perfectly fine. But it’s a kind of homecoming—the book was originally published by Houghton Mifflin in hardcover, and then the license went to Broadway for paperback, which is a division of Random House. After the license expired I brought it back to Houghton Mifflin, so in that sense it feels as if the book is back home.

In preparing for this interview I asked a number of people what questions they might want to ask you, and a number of people contacted me who are currently high school teachers. A couple of them said, I am teaching this book this very week in my class! How do you feel about knowing that so many high schools are teaching this book now?

I have a lot of feelings. I’m really glad—that’s one feeling. I’m delighted. Partly because the book is about writing itself and about story-telling. It’s not just about war. A lot of the book is about what stories are for, and what they do for us. How they carry the ghosts of people around and their memories. They’re about our fathers and mothers and hometowns and boyfriends and girlfriends and wives and children. When you tell a story those people are not physically with you, but they’re with you in a different kind of way. The way they’re with you in a dream, or in a daydream, or in just a quick recollection of your father’s face over a dinner table. The body’s not with you but there’s something there.

In high school, students respond to that, and they write you a letter. They say it reminds me of this, and gives me a sense of peace, or whatever they may say– it makes you feel good. It’s also nice that adults are reading the book. It’s one of those very rare occasions when you feel that you’re reaching not just a specialized audience, but you’re reaching a very diverse audience that takes the book in different ways and has different meanings to people beyond what you would expect.

How has becoming a father affected your writing? Do you find yourself drawn to different themes?

In a lot of ways it’s made it a lot harder! I love my boys a lot and I want to give them all the time I can. If one of the boys comes into my office and wants to play, I play. Whereas before, if someone came in, I’d say, Get lost, I’m writing.

But that’s good. I could never write another word, and I could devote all my energy to my two little boys and I would be a very content guy, because I love them so much, and I would give up anything for them. Including what I have valued most, which is writing. But at the same time, I get good stuff coming out of it. Anecdotes about their lives go into my writing. Words that come out of their mouth are fresh and strange, and combinations of words are very peculiar. And that’s what writing is: a combination of words. So it’s made it hard in some ways to write, but also, I wouldn’t give it up for anything.

Several years ago I saw you speak at the Wisconsin Book Festival. Someone in the audience stood up and asked you for your best writing advice, and I still remember clear as day what you said. You said, “Don’t write bejeweled sentences.” Do you still believe in that?

I do. I don’t think good prose is decoration. It’s like getting a pretty girl and seeing her put all her rouge on, and false eyelashes, and all that stuff that’s chemical and not human. And I feel that way about prose that feels artificially ornate. It’s not that I’m against a good adjective or a good adverb. I’m for it. But I’m only for it if it’s functional and necessary to the sentence. I don’t like decorations hanging off of stories like on a Christmas tree. I think it’s that that I was objecting to.

Did you write at all while you were a soldier in Vietnam?

I did a little. I can’t say a lot, but probably thirty pages handwritten on notepaper. I did it enough to kind of open the door for when I came back to America and began writing seriously. So if I hadn’t begun over there it would have been very hard to start. But at the end of a day, when other guys were horsing around, or waiting for dark to come, they would sort of talk and laugh, and I would sit at the foxhole and I might write a page or two about what had happened that day or the day before.

I wanted to ask about recent literary works that have emerged in the last few years, works written by soldiers stationed in Iraq and Afghanistan. Have you read any of these books? What is your sense of how those works compare to those written by soldiers stationed in Vietnam?

I have read a number of books and magazine articles by veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. I’ve read some really, really good ones, and– as there were in Vietnam– there are some really, really bad ones. By and large really great writing from all wars comes a good time afterwards, when a person has had the time to let material develop and form itself, so that it’s not rhetorical. So that it’s not so heavily autobiographical. The great works to come out of World War II, the great American works to come out of it, took years and years. The Naked and the Dead, Slaughterhouse Five, and Catch-22. They didn’t come the year after the war was over, and I don’t think you can expect that with any war.

It’s a bit like writing about cancer; there needs to be time. You need to find a way to transcend the tendency to put in every little detail. Just because it felt so important, it may not be important to the reader. And time is needed for imagination to come into play and to work with the material, to shape a story that may not be wholly in the real world, but only partly. I’ve read some really fine things that have come out of Iraq, and I’m sure even better things will come out in the years ahead.

Do you feel that there is a different concern in these pieces, given that there hasn’t been an official draft for these wars?

Yeah, there’s a different kind of person who finds himself or herself in Iraq. A person who voluntarily joins the military. And that kind of person is a different person than someone who’s dragged in kicking and screaming as I was, who wants no part, who hates bullets and guns, and doesn’t like sleeping in the dirt. That kind of person is probably going to bring a different mentality and a different temperament; just a wholly differently mindset to war. I’m curious to discover what, in the years ahead, an all-volunteer army will show us. What kind of books will come out of people who intentionally go into the armed forces.

A lot of people question whether this country will ever even be able to have a draft again, given the public backlash during Vietnam. And books like yours, I think, have reinforced the sense that a lot of people may not want to go, and that it’s okay that a lot of people may not want to go. Do you have thoughts about that– that your book has contributed to a national psyche that is resistant to a draft?

Boy, that’s a great question, though I don’t know the answer to it. If there is an answer, I’m not the guy who has it. In the end, I’m just a story-teller, and I don’t mean that in any deprecating sense; I think it’s a grand thing to be. But I’m no sociologist or historian. I’m a person who’s trying to write stories that will get into people’s hearts and their stomachs. And get people to participate in moral crisis and moral outrage and moral hurt. Not just read about it abstractly in a newspaper or see a five-second clip on television.

A book has a way of immersing you in a time and a place and the physical stuff around you. And if you’re lying in bed and you’re reading the book, you’re kind of in it, or at least I am, if the book’s any good. That’s such a different experience from reading non-fiction. The way you feel with a work of fiction if it gets to you, and if you like it, you’ll feel you’re kind of in the book and you’re rooting for the character– you’re almost identifying with that character– and that’s my way of hoping that I can make people feel something that they haven’t felt before.

I’ve tried to pinpoint what exactly it is about your work that seems to be—I don’t know any other way to say it—seems to be written from the inside out, in a way that I don’t often see in other works, fiction or nonfiction. There’s a kind of soulfulness and a sense of urgency that I think is rare. Which authors writing now do you think have those kinds of qualities, that you search for in your own writing, and that you look to put down in your stories?

Again, that’s a good question. I think it depends on where you are in your life, and it depends as much on the reader as it does on the writer himself or herself. I think it wouldn’t be fair, for example, to say to a writer, “You’ve got to write another The Things They Carried.” It would be like asking me to write another Ulysses. One book is itself, and it’s going to remain itself, and I think most writers ought to try to find their own means of looking at their own worlds. How do I tell a story about what happened to me, or what do I worry about out in the world? That’s such a personal passion, a personal concern for the world around you, and then you try to find your own individual ways of dealing with the material, of shaping it, of entertaining people with a story about it, and of wrestling with the underlying human struggles and so on.

Books that are being written today that appeal to me are very rarely books about war. They have to do with the world we’re living in now. Testimony about 9/11—there are some wonderful books about that. And there have been some wonderful works of non-fiction about the era of terrorism and uncertainty as to America’s place in the world. They’re fresh, those books. They’re good. But they have very little relation to the way that I write. Yet they’re wonderful books.

You often appear at the Joiner Center workshop in Boston, and I know you’ve taught at Bread Loaf and other places. Do you feel it’s important to be a mentor to new writers? Do you feel it helps your own work?

I do a little teaching, and it feels important in a number of ways. For one thing, you can get people to read. My students read a lot—things they wouldn’t ordinarily read, probably. And if nothing else, it widens their horizons and it exposes them to different ways of telling stories, and it may change, if only marginally, their standards of excellence. What’s good, what’s bad. What sounds good, what sounds bad.

I teach grammar in my writing courses—I make them learn it. So many come ill-prepared! And I don’t mean that all your characters have to speak grammatically, but I think you have to know it. The same way a mathematician has to know how to add before he can do astrophysics. And in order to do certain characters you have to know grammar. If you want to have some highly-educated English professor as your main character, I’m not going to believe he’s highly educated if he makes errors.

I try to talk about grace and rhythm of sentences and pacing, and the kind of music that underlies prose, that varies radically of course, the way that jazz varies from classical. But I try to talk about rhythm and its importance to a sentence, and not just how it’s important to a sentence, but how it’s important to the story as a whole. It gives a feel to the tenor of a story, to its sadness or its mystery, or its love, or whatever it is—the sentences. All the things like plot and character, they all ride on sentences, on language. They have to—there’s nothing else to ride on except those twenty-six letters in our alphabet. You’ve got nothing else, period. That and punctuation marks.

So I try to make students aware of that. It’s easily forgotten. They try to talk about plot and theme and character, but to get at any of that stuff you have to write sentences. You have to use those twenty-six letters. And I try to make them acutely aware of that, because it will give them the experience to get at the material they want to get at.

Yeah, it does seem like an under-taught topic.

It is. It’s so hard to teach.

You’re trying to teach someone how to have a musical ear.

Sometimes it’s like starting from scratch. A lot of my students– even though they’re MFA students and they’re thirty years old– their grounding in language is not always very good. They don’t pay much attention to it. And I don’t think you can write a very good book if you don’t pay attention to your own sentences.

Do you read any literary magazines regularly?

I do. I read whatever comes across my desk; if someone sends me a magazine I’ll read it. I don’t subscribe to much of anything, except the newspaper, because I get sent so much stuff—books for blurbs and that sort of thing. So I’ve got stacks and stacks and stacks of stuff to read. But if someone sends me a story and asks me to read it, I’ll read it.

Are there any journals in particular that you feel are publishing quality fiction?

There are so many; that’s part of the problem. There’s a wealth of great stories and great magazines. I judged the O. Henry prize two years ago, and I was reading stories from The Paris Review and Tin House and places I’d never heard of. The stories were really good; it was hard to choose a winner. I also read mass national magazines like The New Yorker and so on.

There aren’t as many outlets as there was when I began writing. So many magazines have closed or have stopped publishing fiction. But I’ve seen enough stories come across my desk that are really good that I’m not too worried about it. Somehow they find an outlet, on the Internet or whatever. It will finally get to me if it’s any good.

A number of readers think of you as a “Vietnam writer.” I know that in a number of your books Vietnam is only a backdrop, if it’s there at all. Does that bother you at all, having that label?

I can’t say it does. I have written about Vietnam and it’s important to me, and yet I hear from enough people with no interest at all in Vietnam and still like my work. It’s a little like getting Toni Morrison on the line and saying, “Does it bother you being labeled as a black writer?” And she’d probably say, “Well, I’m black, and it’s been my subject matter my whole career, and I hope I’ve reached beyond it.” And she has. Or like Conrad, who has reached beyond the ocean. And Faulkner had Mississippi. I have Vietnam.

And yet all of us in different ways have used it as a launching pad or a starting place, but in the end I don’t think Faulkner was writing just for Mississippians, and I’m certainly not writing just for people who went through the war in Vietnam. It’s more a vessel that contains the human heart in times of crisis and anguish and joy and everything else that’s kind of a vehicle. It’s not really the subject matter, per se. But I can’t say it bothers me much, no.

What were the books that were most instructive to you as a writer?

It depended on my stage of life. When I was younger, it was The Hardy Boys and Wonder Books, and fairy tales. And then it became the moderns—Hemingway and Faulkner and Dos Passos, Fitzgerald. And I’ve gone through stages—my Nabokov stage has been a building block, not just in my writing alone but in the person I am. I’ve learned to appreciate things I probably wouldn’t have appreciated when I was seventeen, or twenty-two, or whatever the age. That’s how life works. It’s an accretion, and things supplement one another, they become something different. So it’s really a lifetime’s worth of reading that’s stored up inside me.

What are you working on now, if I may ask?

I’m writing a book being an older father, and the squeeze on the soul that that brings to you when you start thinking, “What are things going to be like ten years from now? Will I still be around? Will I still be able to play basketball?” All those ‘what if’ questions. You have this four-year-old kid who loves you and may not have you. The horror, that there’s this kid you love so much, and yet your utter helplessness in the face of biology. I’m writing about love, not of the romantic sort, but for these little boys who one day will go out on their first date, and I’m going to want to go along with a shotgun. But then you have to let go. That sort of thing. The age-old story that could be a Hallmark card, or it could be really good.

What career might you have had if you hadn’t become a writer?

Boy, I don’t know. It’s hard to imagine. I think from the time I was a little boy—maybe eight or nine years old– I dreamed about being a writer, and wanted it. Even though in college I didn’t major in English; it seemed too wild and impossible a dream. And I suppose I thought that being from small-town Minnesota that writers come from big cities. I was just a cow town kid. But I never, in any serious way, thought about what else I would do. You have to remember that when I graduated from college—well, some kids knew what they wanted to do, but I didn’t. And then the draft came along and I was in Vietnam and began writing and haven’t stopped. So there was never really an occasion to say, Well, what am I going to do? I was just already doing it.

Sonya Larson is Program Manager at Grub Street.

This post first ran on Beyond the Margins on March 25, 2010.

Chris Abouzeid's Blog

- Chris Abouzeid's profile

- 21 followers