A healing journey

Nothing ever goes away until it has taught us what we need to learn

~ Pema Chodron

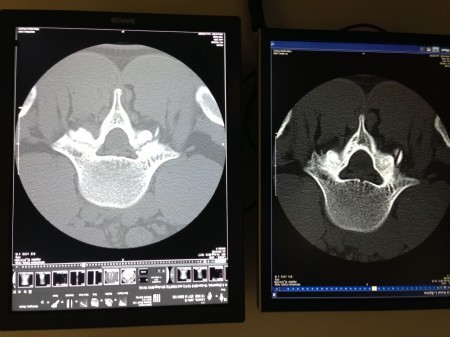

We looked at the X-rays together, my son Jack and I.

“This is last August,” the orthopedist said, pointing to the image on the left, showing two clear fractures in Jack’s L-5 vertebrae, fractures that, after 6 months, were showing no signs of healing on one side and only a minimal feathering of bone growth on the other.

“And this is now,” he said, indicating the scan from last week. “Completely healed.

“I can tell you,” he said turning to Jack and raising his hand for a high five, “this hardly ever happens.”

I remember my very first glimpse of my younger son: the dark, cool room; the ultrasound wand sliding through the goop on my swollen stomach; my husband peering over me to get a look at the shadowy little curlicue of a person floating deep within my belly. It was, I am suddenly realizing, twenty-one years ago this summer – my son’s entire lifetime ago, and yet still fresh and vivid in my mind’s eye. The technician asked if we wanted to know the sex of our baby. Steve and I looked at each other, but he waited for me to say yes.

“It’s a boy,” she said, sliding the cursor over, showing us. I can admit it now: one brief tear slid out of one eye, for the daughter we would never have. And then, in that same moment, we began to imagine our future as the parents of two sons, a family of four. By the time we’d walked back to our car, Jack had a name.

A couple of weeks ago, on the 4th of July, I sat in my brother’s living room watching his little boy do his six-year-old version of a hip-hop dance. Gabriel knows the words to “Stronger,” (though, thankfully, not what most of the lyrics mean) and he has some nasty moves. “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, stand a little taaaaa–ller,” he sang along with Kelly Clarkson, dropping down to the floor, swinging his legs around, thrilled to have an audience.

It’s an old saying, probably true. “What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.” Character is built by adversity. And yet, as my exuberant nephew and his younger sister danced with abandon, all I could think was how beautiful they are in their perfect, tender innocence. And how hard it will be for all of us who love these two children to stand by and watch when, inevitably, life starts roughing them up a bit.

Perhaps it’s human nature: we want to protect our offspring from pain and struggle for just as long as possible. We want their lessons to be painless, the road to be smooth, the waters calm, the sky clear. When the challenges begin, we want to do everything in our power to take the sting out, to ease our children’s way.

How many times did I field calls of distress? “I left my math homework at home”; “I forgot my lunch”; “I lost my sweatshirt”; “Mr. D. was mean to me in class.” My natural inclination, always, was to rush to the rescue — to jump in the car with the forgotten homework, to deliver the lunch, to replace the missing sweatshirt, to make the phone call that would make things better.

Did I do my boys any favors by helping them avoid some of the bumps and bruises of childhood? I’m not sure. Perhaps I made things too easy for them, delayed their understanding that every action has a consequence, that people aren’t always kind, that sweatshirts don’t grow on trees.

On the other hand, perhaps there’s something to be said for knowing, when you’re young and impulsive and distracted and forgetful, that there’s a safety net in place, ready to catch you if you fall.

Eventually, though, life delivers its hard lessons anyway. Kids do stupid things and then have to pay the price for their mistakes. Bad stuff happens, and they must summon enough resilience and moxie to pick up the pieces, dust themselves off, carry on. Our children reach, and fall short. They try, and fail. They hope, and have their hopes dashed.

And somehow we parents must learn to step back and allow them to absorb the hard knocks of growing up. Slowly, and with more than a little heartache, we figure out what our job really is: not to prepare the world to meet our children, but to prepare our children to meet the world — in its splendor, but also in its dark places.

Letting go means putting our trust in the rightness of their journeys and our faith in their resilience. It means remembering that there are larger forces at work in our children’s lives, carrying them to the places they need to go.

Watching my athletic, active, competitive son live with chronic pain over the last eighteen months has taught me a lot about letting go. It was hard to see him suffer. It was just as hard to accept my own helplessness in the face of that suffering. I could make him dinner when he was home, give him some Reiki touch, love him, encourage him. We could pay the medical bills, the physical therapy bills, help out with expenses when he couldn’t work. But whether he recovered or not wasn’t up to us.

Jack has spent much of the last year, while his friends were off at college, on the floor, stretching his hamstrings – the only way to bring the broken vertebrae into proper alignment so they could have a chance to mend. At one point, discouraged and wondering if he would ever again be able to move through a day without pain, he pointed out that at least if he had a broken arm in a cast, people would be able to see his injury. They wouldn’t expect him to lift heavy boxes or carry groceries or shoot hoops. Jack looked fine. He was worried that, to rest of the world, he also looked lazy.

In fact, there was a lot of invisible work going on, and not just in the hamstrings and L5 vertebrae. Much as I might have wished my son to have traveled a different path, much as my heart hurt right along with him during the hardest times, I’ve also come to see this: what he learned this year are lessons that only a dark night of the soul can teach.

He learned that he can do hard things. He learned that pain is often invisible. He learned that empathy begins with the understanding that there is always more going on than meets the eye. He learned that even when dreams shatter and plans go awry, life continues. He learned (a lot) about anatomy. He learned that the rocky road he’s on has its own beauty, its own logic and shifting landscape, its own rightness for him.

Last week, when he was home, Jack spent hours outside in the driveway shooting baskets. He played before breakfast in the morning and under the lights before he went to bed – happy, sweaty, grateful. Nothing like a year of not moving to make every dunk or rebound cause for celebration. He is twenty, and I’m pretty sure he will never again take feeling fine for granted. In the meantime, his plans have changed. In the fall, he’s going to Atlanta, to major in exercise science and nutrition in a pre-chiropractic program at Life University. “I like the idea of helping people,” he says. “When someone comes to me in pain, I’ll know how they feel.”

How little I knew twenty-one summers ago, as I gazed at that first hazy gray picture of my younger son, floating in amniotic fluid. All I could do then, as he grew deep inside me, was say “yes” to him, to the mystery of this unknown being, to my innocent faith that things would all work out. They have. They do. In ways I never could have anticipated, never would have chosen, wouldn’t change.

What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger, stand a little taller. Yes. And this, too, from poet David Whyte:

To be human

is to become visible

while carrying

what is hidden

as a gift to others.

(And thanks to Jack for giving me permission to share his X-ray.)

The post A healing journey appeared first on Katrina Kenison.