The DC Comics Offices 1930s-1950s Part 5 (final)

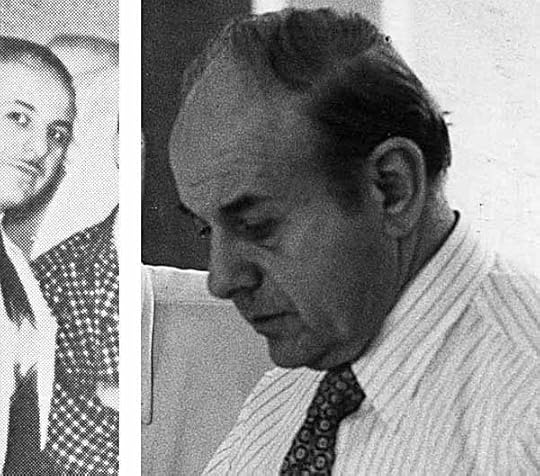

Jack Adler at the Photochrome Engraving Plant at 487 Broadway, 1943, and Jack Adler in the 1970s, photos © DC Comics, Inc.

Jack Adler at the Photochrome Engraving Plant at 487 Broadway, 1943, and Jack Adler in the 1970s, photos © DC Comics, Inc.

Wrapping up this tale of the DC offices, we continue further into the 1950s. Sol Harrison and Jack Adler, the same age, were friends in high school, both learning the engraving business from a teacher named Jack Fabrikant. They often worked together, sometimes separately, at various engraving companies around Manhattan and frequently on early comics. In 1943, when Sol took a job as Art Director, and then shortly after as Production Manager for All-American Publications, Jack was still working at Photochrome Engraving. When All-American was bought by National Comics and moved to 480 Lexington Avenue, Sol began creating color guides for all the covers for the company, but the rest of the coloring process was still being handled largely by the engravers. In a 1970s interview in THE AMAZING WORLD OF DC COMICS #10, Sol remembered, “We had the problem that we’d always have to tell the engraver what we wanted. The explanation (for any changes or problems) had to go through three hands before it was finally done.” Jack Adler said, “(Sol) felt it would be to the advantage of National (Comics) if we came over and did the (cover) separations there, and got an allowance from the engravers for it, and then you’d have (a) type of separations that were different from everybody else’s.” Sol added, “I called Jack, Jerry Serpe and Tommy Nicholosi and set up our own color separation department. We color separated all our covers and advertising.” Jack placed the date of this, when he came to National Comics, as January, 1951, when he was 34.

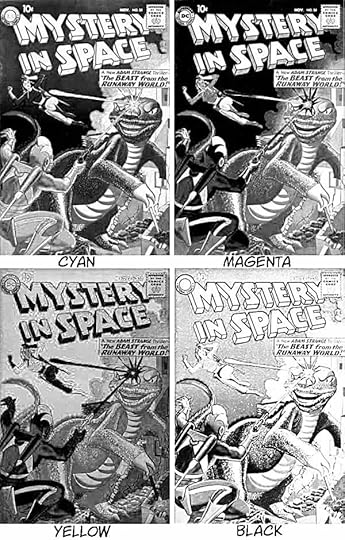

MYSTERY IN SPACE #55, CHALLENGERS OF THE UNKNOWN #6, © DC Comics, Inc.

MYSTERY IN SPACE #55, CHALLENGERS OF THE UNKNOWN #6, © DC Comics, Inc.

The kind of cover separations that Jack Adler and his crew were able to create by doing it themselves did, indeed, set many of the National Comics covers apart from and ahead of their competition. However, these types of covers with fully rendered shading and gray tones don’t start showing up until around 1957. What Jack might have been doing as early as 1951 is less clear.

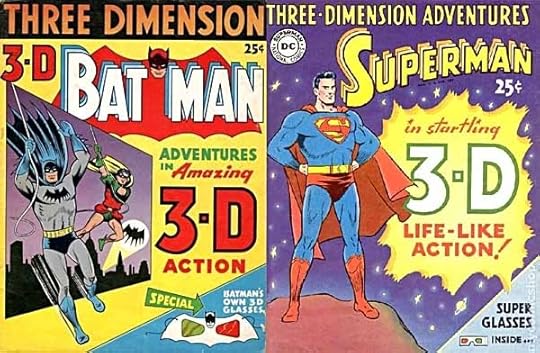

Batman and Superman 3-D Comics, 1953, © DC Comics, Inc.

He did work on the first 3-D comics at National, though, in fact he created the 3-D process used to make them, and those came out in 1953. Jack went on to become Sol’s assistant production manager when Eddie Eisenberg left the company (Irwin Donenfeld mentions in a 2001 interview he had to lay Eisenberg off, without giving the date or the reason), and in the 1970s, Jack became the Production Manager himself.

MYSTERY IN SPACE 55 cover, separated into color plates (an approximation using Photoshop on a scan of the printed cover), © DC Comics, Inc.

Jack’s artistic talent was unmistakeable, especially when you remember that each of the four color plates (Magenta, Cyan, Yellow and Black) on his covers had to be painted separately in gray watercolors. Jack knew from his long experience as an engraver how it would come out! Jack Adler was the man who hired me in 1977, and I learned a lot from him in the few years we worked together. He left staff in 1981.

Of the others in the new coloring department, I’ve found out nothing about Tommy Nicholosi. Jerry Serpe was still coloring lots of comic book pages when I was on staff from 1977-87, creating color guides for the separators at Chemical Color in Bridgeport, CT to follow in creating the actual color plates. Jerry was 38 in 1957 when he was helping create the new standard for comics coloring. He died in 2008. I’ve found no photos of him.

Clearly by the 1950s, color was getting more attention from the company, as opposed to the early days of comics when they let the engravers make most of the color decisions, and the addition of Jack Adler and his cohorts greatly enhanced that.

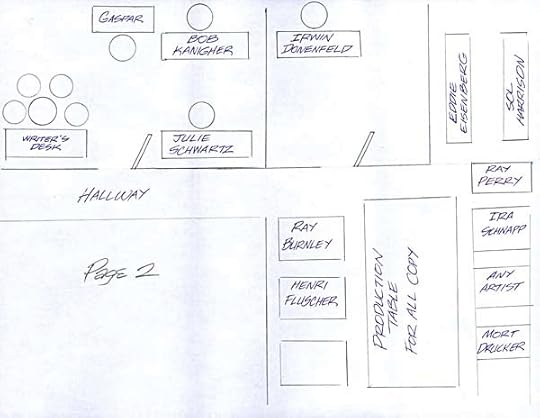

Floor plan of part of the National Comics offices at 480 Lexington, © Gaspar Saladino.

As to where the new color department might have fit into Gaspar’s floor plan, I can only speculate. It seems unlikely they would have filled the open desks in the production room, which were needed for artists. Perhaps Irwin Donenfeld moved to Whitney Ellsworth’s office after Whit left the New York staff in 1953, and the colorists sat there. It seems likely that Jack Adler would have taken Eddie Eisenberg’s spot at some point.

The personnel in the production department went through changes as the 1950s continued. Elderly Raymond Perry left,, as did young Mort Drucker to pursue his freelance career. One new hire was Morris Waldinger, who I believe joined the company around 1954, when he was about 25 years old. I worked with Morris, or Moe as we called him, for a year or two before he was laid off during the DC Implosion in 1979, but never found out much about him or what he did later. Alex Jay has discovered he died in 2006. I have no pictures of Morris.

Joe Letterese, early 1950s in the Atlas Comics bullpen, photo from FOOM #17, © Marvel Comics, Inc. and Joe in a photo by Jack Adler, 1970s, courtesy of Mike Catron.

In 1956 Atlas Comics was forced to drastically cut staff after losing their distributor. One of their production men, Joe Letterese, soon found his way to the National Comics production department, where he spent the rest of his career. He and Morris were buddies, and spent lots of time talking and joking together. I worked with Joe until he retired in the early 1980s. Another casualty of the Marvel cutbacks was Stan Starkman, who may have also spent time in the DC bullpen in the 1960s, don’t know when he started or how long he was there. Rumored to have briefly been in the National production room was famed illustrator Maurice Sendak, though I’ve found no proof of that.

While most of the National comics continued to list Whitney Ellsworth as editor through the early 1950s, Zena Brody’s name did appear as editor on a few issues of SECRET HEARTS beginning in 1955, and is considered to be the editor of the romance comics into 1957. In a 2001 article in “The Comics!”, Robert Kanigher says, “She eventually left to marry her childhood sweetheart, a doctor from Mt. Sinai Hospital.” In his 2001 interview, Irwin Donenfeld says, “Zena Brody was the first editor of our romance books and she died. It was a horrible thing. She was young and a really beautiful woman. She had a brain hemorrhage and died. She was only in her 20s or 30s.” This is a troubling dichotomy. I suppose both of these stories could be true, if the marriage happened, and then the hemorrhage, but we’ve found no evidence of either. In any case, Whitney Ellsworth’s name went back on the indicias as editor for a while.

In his article, Kanigher says, “Whit asked me to perform the same (editorial) instruction for Ruth Brant, from Fargo, North Dakota. She inherited the same group of writers that Zena did. She was very conscientious and a very good romance editor.” This sounds plausible, though Ellsworth was long gone from the staff by that time, and Brant’s name never appeared in a comic as far as I can tell. Robin Snyder tracked her down, but only after her death in 2011. She was born in 1921, so would have been 36 in 1957 if she took over for Zena Brody then. Robin reports her married name as Ruth Brant-Croal and that she graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Barnard College in New York. Robin says she left New York to return to North Dakota around 1959.

Phyllis Reed by Jack Adler, 1950s, courtesy of Mike Catron.

The next editor of record on the romance books is Phyllis Reed, probably 40 years old in 1958. Her name appears on indicias from March, 1958 to July, 1963 cover-dates, so perhaps Ruth Brant’s tenure was shorter than Kanigher remembered. He does have a lot to say about Phyllis, though. In his 2001 article, he writes: “I accidentally met Phyllis Reed, DC switchboard operator, at the Museum of Modern Art. We toured the exhibitions, arguing. Phyllis was pro-Jackson Pollack, and I was con. We had coffee and a sandwich on the steps of the garden.

“Phyllis asked me whether it was possible for her to learn to write romance, to augment her salary as a switchboard operator.”…”The steps leading to the garden of the Museum became our daily ‘Classroom.’ I taught Phyllis the importance of visual openings, character, passion, conflict and unexpected endings, if possible. She was a quick study. She was working on her first script using a carbon of one of mine as the example.

“I read Phyllis’ first script. It was unusable. I had to shred it. It was simple for me to write a new script in its place. How could I pay her? I couldn’t voucher a switchboard operator. But I could voucher her husband. I hadn’t the heart to tell her that every time she brought in a script, I junked it and wrote a replacement, sending the check to John Reed. We continued in this practice for several years through dozens of romance, western and war stories.”

Having transcribed all this, I have to say most of it sounds highly unlikely to me. I can see Kanigher taking on Phyllis as a student, and perhaps helping her by rewriting her work at first, but several years? And completely replacing her work with his own? Who would accept that? Second, the idea that he couldn’t pay her directly doesn’t sound likely either. Practically the entire staff of the company did some kind of freelance work on the side to augment their salaries, it’s the way things were done then, and still so in the decade I was on staff. Any company employee with ability could do the same.

Of Phyllis Reed becoming editor, Kanigher writes: “I argued with the Top Brass and finally convinced them that Phyllis would make a solid editor, replacing Ruth. She served in that position for several years before taking early retirement.”

All I can say is, take what you will from Kanigher’s essay. Me, I’m keeping in mind what a great storyteller the man was. Phyllis died in 2005.

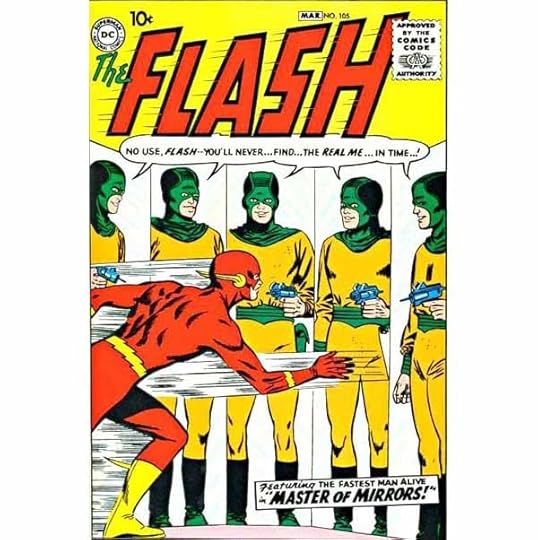

FLASH #105, 1959, © DC Comics, Inc.

Here’s the issue that heralded the immediate future for National Comics, the Silver Age of Super-heroes, led by editor Julius Schwartz. It’s the first of a monthly revival after successful tryouts in SHOWCASE. Note also the large Comics Code seal of approval, the industry reaction to witch-hunts and mass burnings after the excessive gore and blatant sexuality of some comics in the early 1950s, and the over-reaction to them. At National, sales were down from the glory years of the early 1940s, but they were trying to compensate by publishing lots more titles, including some they bought from Prize and Quality when those companies folded. In 1959 the editorial lineup was:

Mort Weisinger, editor: ACTION, ADVENTURE, JIMMY OLSEN, LOIS LANE, SHOWCASE, SUPERBOY, SUPERMAN.

Jack Schiff, with George Kashdan and Murray Boltinoff, editors: BATMAN, BLACKHAWK, CHALLENGERS OF THE UNKNOWN, DETECTIVE, HOUSE OF MYSTERY, HOUSE OF SECRETS, MY GREATEST ADVENTURE, TALES OF THE UNEXPECTED, TOMAHAWK and WORLD’S FINEST.

Larry Nadle, editor: ADVENTURES OF BOB HOPE, A DATE WITH JUDY, FLIPPITY AND FLOP, FOX AND CROW, PVT. DOBERMAN, REAL SCREEN COMICS, SGT. BILKO, SUGAR AND SPIKE, THREE MOUSEKETEERS.

Julius Schwartz, editor: ADVENTURES OF REX THE WONDER DOG, ALL-STAR WESTERN, THE FLASH, HOPALONG CASSIDY, MYSTERY IN SPACE, STRANGE ADVENTURES, WESTERN.

Phyllis Reed, editor: FALLING IN LOVE, GIRLS’ LOVE STORIES, GIRLS’ ROMANCES, HEART THROBS, SECRET HEARTS.

Robert Kanigher, editor: ALL AMERICAN MEN OF WAR, BRAVE AND BOLD, G.I. COMBAT, OUR ARMY AT WAR, OUR FIGHTING FORCES, STAR-SPANGLED WAR STORIES, WONDER WOMAN.

The business had long outgrown their office space, and National Comics would move to 575 Lexington by 1960, soon taking on the name National Periodical Publications, Inc.

480 Lexington Avenue today, photos © Alan Kupperberg, 2013.

480 Lexington itself was feeling its age. The Grand Central Palace stopped being used for trade shows in the mid-1950s, giving way to more modern venues like the New York Coliseum, which opened in 1956. The building which housed the Donenfeld publishing empire for about 28 years was demolished in 1963, and a new, much larger building now occupies the site. The address of 480 Lexington survives, however, and will long be remembered by comics fans who pay attention to such things.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND SOURCES

This article began as a much simpler look at the DC offices in the 1950s, but as I gathered information it kept growing, becoming the most time-consuming blog article I’ve yet undertaken. I couldn’t have done it without the help of these people:

ALEX JAY, researcher extraordinaire, and sounding board for my own research. Visit his own website for more of his research and design articles.

GASPAR SALADINO, for his floorplan and memories. His daughter LISA WEINREB for a great photo of her dad.

PAUL LEVITZ, author of new DC histories published by Taschen, and of much help with photos and advice.

KEN NADLE, son of editor Larry Nadle, for photos.

MIKE CATRON, for permission to use the Jack Adler photos in his DVD “A Salute to Jack Adler.”

ALAN KUPPERBERG, for being my photographer on the street in Manhattan.

NEAL ADAMS for photo advice.

JACK C. HARRIS, MICHAEL T. GILBERT, ROBIN SNYDER and MARSHA MILLER for research help.

Here are some of the sources cited or referred to in the writing of the article, I highly recommend them for further reading:

“The Golden Age of DC Comics,” by Paul Levitz, published by Taschen, 2013.

ALTER EGO #7 (Julius Schwartz interview), ALTER EGO #26 (Irwin Donenfeld Interview), ALTER EGO #72 (Ken Nadle article about Larry and Martin Nadle), ALL-STAR COMPANION VOL. 1, all edited by Roy Thomas and published by TwoMorrows. Online excerpts from other issues were also consulted. Most or all of these are available as downloads on the TwoMorrows website.

THE AMAZING WORLD OF DC COMICS #10 (Interviews with Sol Harrison and Jack Adler by Carl Gafford), graciously sent to me by someone whose name I’ve misplaced.

COMIC BOOK MARKETPLACE #88, December, 2001, Gemstone Magazines (reprint of the 1957 article from “Newsdealer” by Lloyd Jacquet)

THE COMICS! Vol. 12 #6, June, 2001, published by Robin Snyder (Robert Kanigher article on National romance comics)

The DC Timeline Website by Bob A. Hughes, compiled from many sources, listed there in his Bibliography.

And many other sites, articles and resources found through Google too numerous to mention.

If you enjoyed this article, you might want to continue with Visiting DC Comics in the 1960s and The DC Comics Production Department, 1979 as well as other articles on my COMICS CREATION and LOGO LINKS pages.

Comments and corrections are always welcome, though I can’t guarantee I’ll act on them. Thanks for reading!

Todd Klein's Blog

- Todd Klein's profile

- 28 followers