The South Carolina Nullification

South Carolina’s response to perceived onerous federal taxation led to one of the first major sectional conflicts in U.S. history and helped sow the seeds of civil war.

In 1828, a new tariff law was enacted that raised taxes on foreign imports to unprecedented levels. The law’s supporters were mostly northerners who believed that higher taxes on imports would protect northern industrial goods from European competition.

However, the law disproportionately harmed the South because that region relied more on foreign imports than the North. In addition, high tariffs could prompt foreign trading partners to retaliate with high tariffs of their own, which could disproportionately harm the South because southerners relied more on exporting their goods than northern manufacturers.

In reality, the tariff was not raised to protect U.S. industry. It was a political ploy to help Andrew Jackson get elected president. Exorbitant taxes were placed on goods manufactured in New England, which was the home of current President John Quincy Adams. When Adams signed the bill into law, he was accused of favoring New Englanders over southerners, and his prospects for reelection in the upcoming presidential election became slim.

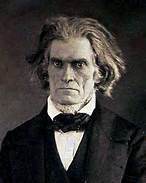

Southerners condemned this new law, calling it the “Tariff of Abominations.” An anonymous pamphlet called “The South Carolina Exposition and Protest” was distributed that declared the tariff was “unconstitutional, oppressive and unjust.” According to the pamphlet, “The United States is not a union of the people, but a league or compact between sovereign states, any of which has the right to judge when the compact is broken and to pronounce any law null and void which violates its conditions.” The tract’s author was later revealed to be Vice President John C. Calhoun of South Carolina.

John C. Calhoun of South Carolina

Calhoun’s theory of nullification was not an original idea. The original nullification document was the Declaration of Independence, in which Thomas Jefferson proclaimed that the states were independent of Great Britain and therefore no longer subject to her laws. Jefferson and James Madison also encouraged state resistance to federal authority in the Virginia and Kentucky Resolves of 1798. In addition, many northerners also supported nullification, especially abolitionists who urged people to ignore laws that upheld and enforced slavery.

Many founders believed that since the federal government derived its power from the states’ consent, the states had the inherent right to defy federal laws considered harmful to their existence. Much state resistance to federal power stemmed from the War for Independence, which was a war of secession from Great Britain. American fears of a tyrannical central government prompted many to declare greater loyalty to their state than the federal authority. To southerners, an unfairly high tariff constituted federal tyranny.

As planned, Andrew Jackson was elected president shortly after John Quincy Adams approved the high tariff. Southerners supported Jackson in the hope that as a fellow southerner, he would be sympathetic to their interests. When prospects of the desired sympathy turned bleak, cries grew louder for nullification, and Vice President Calhoun declared support for the nullifiers.

Tensions between Calhoun and Jackson climaxed at the annual Jefferson’s Birthday Dinner in 1830. Proposing a toast, Jackson declared, “Our Union! It must be preserved!” Calhoun countered by declaring, “The Union! Next to our liberty, the most dear!” The following year, Calhoun delivered a speech:

“Stripped of all its covering, the naked question is, whether ours is a federal or consolidated government; a constitutional or absolute one; a government resting solidly on the basis of the sovereignty of the states, or on the unrestrained will of a majority; a form of government, as in all other unlimited ones, in which injustice, violence, and force must ultimately prevail.”

Calhoun ultimately became the first vice president to resign when the South Carolina legislature elected him to the U.S. Senate. Calhoun encouraged his fellow South Carolinians to oppose federal enforcement of the tariff.

In an effort to ease the bitterness, a new tariff law was enacted in 1832. Although this generally lowered the tariff rates, the decreases were not enough to appease South Carolina. On November 24, a state convention passed an “Ordinance of Nullification” which declared the tariff “null, void and no law.”

President Jackson furiously declared that no state could nullify a federal law and he initiated the Force Act, which empowered him to mobilize the U.S. military to collect tariffs if necessary. Jackson ordered General Winfield Scott to prepare to lead 50,000 troops into the state, and he ordered a naval squadron at Norfolk to prepare to go to Charleston. South Carolina officials condemned “King Andrew” and mobilized 10,000 state militia to repel a potential invasion. Meanwhile, politicians led by Calhoun and Henry Clay scrambled to find a compromise to avert war.

Congressmen eventually agreed upon a new law known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833. This gradually reduced taxes on imports over 10 years in exchange for South Carolina revoking the Ordinance of Nullification. After all parties agreed to the terms, South Carolinians symbolically voted to nullify Jackson’s Force Act. It was a final act of defiance, even though the Force Act was never implemented.

Both sides claimed victory in the tariff standoff. Some saw this as a defeat for the theory of nullification, and others saw it as a southern victory because tariffs were ultimately lowered. Many southern states began citing this incident as an example that states were empowered to secede, and the flames of secession began growing hotter. While the compromise temporarily pacified both sides, the tariff would be one of key issues that would divide the North and South for the next 30 years and lead to civil war.