R.I.P., my darlings

The omitted first five chapters of Cry of the Peacock have been reworked into a short story. See below for links to this FREE bonus material.

I believe it was Stephen King who said that writing never gets easier. This is both absolutely false and entirely true. As I gain experience and practice, as I allow my editors (and my readers, too) to teach me, I find that forming stories, the plotting and characterization, grows much easier. But there’s something about having been published and having faithful publishers, editors and readers, that makes one grow a little lazy. I no longer want to kill my darlings. I see no reason why my 185,000 word book must be 150,000 or fewer words. I do not like to kill my darlings. They are, after all, my darlings!

(Excuse me a moment while I weep.)

The truth is, making big cuts is a LOT of work. And while there is the incentive of making the work more concise, every cut has consequences. One omission creates a domino effect, chapters and scenes must be rewritten. Motivations change. Characters have to think of different things to say and different ways to say them.

It hurts cutting out those words. It really, really hurts.

Because I’ve been working on Cry of the Peacock the longest, I think it was the hardest to edit. Those darlings were family members, and to excise them was a little like sending a child off to college. Or worse…

But the fact is, because those words, those scenes and lines of dialogue had been there so long, I had decided they belonged even when they ceased to do so. Reworking of the story meant that other scenes were doing the work those old scenes had done, and were doing it in a more natural manner.

Still, some of what was cut out in those final edits was my finest writing. But then…they were my darlings, so of course I think so. For my own pleasure perhaps more than anyone else’s, I offer here a few of those deleted scenes. If you’ve read the book, you will see that they are no longer necessary. If you haven’t, I hope it intrigues you.

First however, an anecdotal note. Cry of the Peacock has been read by many, many beta readers in the form of Kentridge Hall. I liked that title, but in the end it changed with the renaming of the major characters—which, for the record, I did not want to do. It was necessary however, because a certain author, who I shall not name, got it into her head to name her characters Edward and Bella. Yes, that’s right. Once upon a time, Arabella Gray was Isabella Hampstead. And Ruskin Crawford was Edward. *sigh*

Have you ever considered renaming your children? No? There’s a reason for that.

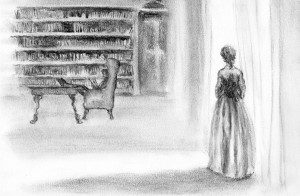

The first offering is what I call The First Library Scene, where Abbie, anxious for some more thought provoking reading than Lady Crawford has so far provided for her, discovers an abandoned library, where the old and lesser used books of the house are kept. She quickly discovers she’s not alone.

She stood before the door. Tapped lightly (very lightly) and turned the knob. The door swung open without a sound, and she was soon inside and searching the shelves with ravenous curiosity. Only the books were so old, the room so dark, she found it a challenge to distinguish the titles. She crossed to the windows and drew the curtains open, sending clouds of dust to dance across the rays of sunlight that now entered the room unhindered.

“Good grief! Was that really necessary?”

Abbie started and turned, and discovered James sitting in a far corner of the room, half concealed in the recesses of an immense wingback chair and blinking in the light. It seemed she’d awoken him.

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know anyone was here. I did knock.”

“The light reading is kept in the music room, you know.”

“I know where the light reading is, thank you,” she said, bristling. “But, as it happens, it isn’t light reading I want.”

He examined her a moment in silence. “Perhaps you want Aristophanes in Greek,” he said at last.

“Who’s to say I don’t? Not you.”

He arose from his chair. She did not like the faintly predatory look in his eye any better than the patronizing tone of his voice.

He approached, stopping just before her and looked at her very pointedly before raising his gaze to the shelves just above her head.

“Here we are,” he said and pulled down a well-worn leather volume. He opened it, scanned the pages for a moment, and then began to read.

She lives on apples and cheese

Yet she got herself appointed

Heiress to an estate

Way out there in Hamp—”

“That’s not what it says,” she objected and tried to take the book. But he held it away from her, and with an eyebrow raised, challenged her to prove it did not. At last he turned the volume so she could see it. It was, indeed, in indecipherable Greek.

“I expect you miss your sister very much,” he said, closing the book and replacing it on the shelf. “Pity she couldn’t come with you.”

“And would you have treated her with any less contempt than you have so far treated me?”

“Contempt? I wouldn’t call it contempt. Doubt, perhaps. Scepticism.”

“In my abilities?”

“I couldn’t care two figs about your abilities, Miss Gray. Perhaps a better word would be suspicion.”

“Suspicion? What can you possibly suspect me of, Mr. Crawford?”

He gave her a sideways glance and returned to his chair, putting his feet up on a nearby table and taking up the book which he may or may not have been reading, in the near darkness before he had fallen asleep.

“You seem not to have heard me, Mr. Crawford, so I’ll repeat the question.”

“I heard you. What do you think I would suspect you of, Miss Gray?”

“I haven’t the faintest clue.”

“Let me help you, then. Imagine, for a moment, someone in my position—”

“A rich, spoiled wastrel and a rogue? I suppose that’s easily enough done.”

His gaze narrowed for a moment. “Well-bred, well-educated and born to privilege is the way I would prefer to put it.”

“I’m sure you would.”

“And expected to preserve the traditions and accepted protocol of our set.”

“I don’t know what any of this has to do with me.”

“Imagine you,” he continued, “from a sphere decidedly lower, having no claims upon us that I can possibly imagine, and yet here you are! How did you manage it? What kind of avaricious schemer must you be?”

“I was invited to come, Mr. Crawford, in case you’d forgotten.”

“Yes, yes, the invitation was issued,” he said and waved it away. “But you sought it, won it somehow. Admit it. Owing to your skill, I suppose, you wheedled your way in. Congratulations on a job well done, but don’t make the mistake of thinking yourself one of us just because you have learned to look and act the part. Go back to your people, Miss Gray. Lay aside your contemptible ambition and go back where you belong, before you find yourself in deeper water than you can swim.”

“Am I a threat to you somehow?”

“A threat?”

“Yes. I cannot account for your contempt unless you somehow consider me a threat in some unimaginable way. Do you, Mr. Crawford?”

“Not in the least! I’m simply trying to mitigate the damage you are sure to cause when your schemes fall through and all you have left is your embarrassment, of which the family, if you insist on pursuing your aims, must share.”

“You don’t know what my aims are. Or you’ve decided them for me, in which case, perhaps I should thank you, as I hardly know them myself just yet. I thought we would have a shared interest in those I have dared to form, but I can see that I was wrong.”

“A shared interest? In what possible way?” he asked and laughed condescendingly.

“And you speak of embarrassment, Mr. Crawford. It seems a trifle hypocritical to me to be speaking of the embarrassment I must no doubt cause your family, when you are the one in the habit of daily shaming them.”

“You know me so well!”

“I know enough. Your reputation is no secret. I’ve seen with my own eyes how your kind make a game of life and death. You have your fun and leave the mess for someone else to clean up. Ruined women, fatherless children, hearts broken and lives and dreams dashed. And why? Because you can? Because somehow you have the right to make spoils of other people’s lives? Because you have the money and station to protect you where another man, and any woman, would have to step up to their responsibilities? All I want from your family, Mr. Crawford, is the protection they offered to provide. And you would cast me off? Why? For no other reason than that I am inconvenient to you? You are inconvenient, Mr. Crawford, not to me, but to those whose happinesses you trifle with.”

James did not answer her, but the look in his eye was almost fierce.

“Is everything all right here?” Ruskin said as he entered the room. “I thought I heard voices,” he said to Abbie as she turned to face him. “Is something the matter?”

“James and I were just having a little difference of opinion.”

“Between brother and sister,” James added.

Ruskin cast James a warning look, then turned once more to Abbie. “Where is your companion?”

Suddenly she was conscious that she had not behaved quite correctly. She had evaded her maid, to be discovered in close conversation, alone, with James. She did not even know that the library was a room in which she was welcome to visit. She hadn’t been forbidden from it, but Ruskin’s manner when she had been discovered here before was not entirely inviting, at least as far as the room was concerned.”

“I was just looking for something to read.”

“There isn’t much here, I should think, that you would find of interest.”

“No, that’s what James said,” she answered with the slightest hint of irritation.

“What I mean is,” he added, “there isn’t much here to interest anyone. James’ abandoned attempts at scholastic achievement are kept here. Books we no longer use for managing the estate. Census records, tax and tithe records, family records, that kind of thing. Of course you’re welcome to any of it. I would just be surprised if you found anything here worth reading.”

“She seemed rather taken with Aristophanes.”

“Certainly not with your translation of it,” she interjected. “Perhaps I’ll just go see what the music room has to offer.” She turned to go.

“You needn’t, you know,” Ruskin said, stopping her.

She turned back again.

“At least, it is not unthinkable that you should have your own room to read in. If you want it that is.”

She looked at him, unbelieving.

“It’s a small thing, Miss Gray, that we might do to make you more comfortable. You should have a room of your own, safe from interruption,” he added with a meaning glance in James’ direction, “and all the reading you should wish.”

“Do you mean it?” she asked him.

“The idea pleases you?”

“Good Lord!” James said and raised his book once more.

“It pleases me very much,” she answered. “Though I hope it won’t be an inconvenience.”

“None whatever.”

James laughed out loud and threw his book aside. “You’re always so insufferably polite, Russ.”

“You think I should be more like you, do you?”

“I’m sure Miss Gray values honesty. You should tell her you had hoped to have this room as your own.”

“Is this true?” she asked him.

“Once, perhaps.”

“And no longer? Why? Not because of me?”

“No,” Ruskin said. “You are my consolation.”

“Steady on, old man. Don’t put the cart before the horse.”

The look Ruskin turned upon his brother now was almost murderous.

“What I meant,” he said, and then, relaxing his features as he turned them upon Abbie, “was that it would be a comfort to know it was going to a good cause. I had once thought to have it for my study. I like the idea of your having it much better. It will take some doing, I’m afraid, to put it in any kind of presentable state. You will be patient?”

“Yes, of course.”

“Good,” he said and looked quite pleased, which, in turn, pleased her very much. How kind he was next to James’ insolence! “I’ll leave you then,” he said, “so that we might begin right away.” He bowed, then called after him, and without looking: “James!”

James cut an exaggerated bow in his brother’s direction, but Ruskin had already gone. He started after him, but then stopped at the door. “I do not know how you do it, Miss Gray, but perhaps it would be worth the time to study your methods.”

“What can you mean?”

“You came in here for a book. You leave with a library. Monarchs could learn a thing or two from you, I should think. If you’ll excuse me,” and with a smug smile, he turned to go.

“As you have so adroitly pointed out,” she said stopping him.

He did not turn around.

“. . . I place high regard in the virtue of honesty, so, let’s be honest with each other, shall we?”

He turned then, and bowed his head. “By all means, Miss Gray.”

“I know now what you think of me and why. I should perhaps take it as an example of what others will no doubt think as well. I was wrong to believe I could overcome such prejudices. Likely it will make no difference, but perhaps you should know that it was only as a last resort that I finally agreed to accept your family’s very generous invitation. I am now in a position to be envied by some and despised by others. However, I come to you reluctant, expecting nothing, hoping for nothing but the protection your family was so good as to offer me. It is not my intention to repay that kindness by disgracing myself or causing embarrassment or disappointment to those who have been so good as to think kindly of me. But I am not without hope that I can live up to expectation, however far beyond my own it may be. It’s true I was not born into this world, and so have no right to it, but neither am I so removed from it as you suppose. Do not forget that my mother was once a neighbour of your own—”

“What?” he asked, actually demanded, and looked, for the moment, stunned.

“Of course you knew that.”

“I—” But he said nothing more, and so Abbie went on before she lost her nerve entirely.

“My mother, as it may very well surprise you, was in no way proud of her connections. She walked away from her family, happily left her former life behind her. She never spoke of her history or gave us any reason to believe she regretted her choice. So while you are no doubt suspicious of me, you must believe me when I say that I have my own misgivings in respect to what my future here may hold. You’ve made it sufficiently evident that you do not welcome me here, and I take it very seriously as a warning of obstacles to come. Had I anywhere else to go, any place safer, any place more likely to ensure my protection, regardless of my own personal ambitions, you may rest assured—”

He held a hand up to stop her. “You’ve said quite enough, ma’am,” and he turned and left the room. But not without nearly bumping into Sarah. He avoided her, without a word, and was gone.

Omitted illustration, by the incomparable artist, and fellow author, B. Lloyd.

The second offering takes place as Abbie and James are returning from touring the estate. Originally it had been my intention to have Abbie revisit her old home at Oak Lodge. The necessity for this scene grew questionable over time, though it still seems to me something she might very much have liked to do, had she been granted the opportunity. You’ll be able to see how I had to rework James’ finding of Mariana’s photograph. I almost like this better. Alas… Sacrifices had to be made, and in the end, I believe Cry of the Peacock is a far better book than Kentridge Hall ever was.

They had reached the copse of trees which divided the Holdaway estate from Whiteheath, before James spoke again. Oak Lodge had just come into view, and Abbie was looking at it longingly. And was conscious of doing so.

“Would you like to stop?” he asked her.

She hesitated a moment, not unsure of her answer, but of her companion. “Yes,” she said. “Very much.”

They descended the hill, where the cottage was nestled quite comfortably in the little hollow of land. They arrived at the door and dismounted, yet Abbie hesitated at the front door a moment.

“You don’t mind?” she asked him.

“I don’t mind,” he said and tried the door. It was fastened tight.

Abbie produced the key, concealed within a potted plant, and entered the cottage.

* * *

James, his curiosity high, alternately examined the quaint interior and her reunion with it. Her things, packed and crated and boxed, remained where they had been left.

“I thought Sir Nicholas was going to see that it was all put in storage,” she said to him.

“It’s safe enough here.”

“Until there are new tenants.”

“I’ve heard no talk of letting it again.”

“So it will just sit?”

James shrugged and watched her as she looked around, afraid, or so it seemed, to touch anything at first. And then, tentatively, as if none of it were hers after all, or had ever been, she drew her fingers across the surface of a nearby table, draped in a dust cloth, then a stack of pictures covered similarly. Her hand lingered, then pulled the cloth away, revealing the portrait of a woman not unlike Abbie.

“Your mother?”

“Yes.”

“I see where you get it, then.” He shouldn’t have said it. It was snide remark, nothing more than a thought spoken aloud, but he was a fool for thinking it at all.

“Get what?” she asked.

He chose not to answer her, but she, as women are so often wont to do, would not leave it alone. “What is it you discern from the portrait, Mr. Crawford?” she asked him, an air of disdain creeping into her own voice now. She was quite the defensive little thing, wasn’t she? “Perhaps it’s apparent from my mother’s image, how out of place in your world I must by birth and circumstance be.”

She was speaking sarcastically, of course, for it was no mean painting, this, but one commissioned by an apparently skilled artist. The frame alone was likely worth a small fortune. Save for the humbleness of the cottage itself, which was veritably a palace next to that which they had just left, the evidences of her family’s former wealth were everywhere to be seen. The few visible furnishings were of the finest construction. The unsealed crates, which here and there sat open, contained an enviable collection of leather-bound and gilt edged books. The household appointments, from the papers and curtains and upholsteries, showed a taste that was highly cultivated. Such does not happen by chance.

“Because of my family’s embarrassment, am I utterly to be despised?” she said now.

“I never said, nor did I mean to imply, anything of the sort. You cannot help your history, of course. It’s your plans for the future that concern me.”

“That’s what you saw in the portrait? My plans?”

He simply shook his head and turned away.

“Do you mean to explain yourself, Mr. Crawford?”

“No. As a matter of fact, I don’t.” If she had been playing coy, the flirt, the inveterate charmer, she would have taken his meaning already and used it to her purpose. She had not, and he found it curious.

He turned again to watch as she fingered the books that lay in a nearby crate. “Perhaps it was my appreciation for Greek prose, then?” she said and took up one of the books, veritably thrusting it at him. It was Aristophanes, indeed, though an English translation. Which would explain how she knew what The Frogs did not say.

“You know, I think that must have been it,” he said, and could not resist a mirthful smile. She’d made her point, it seemed. And cleverly at that. He laughed then and her look of defensive irritation faded. She smiled, shook her head, and, at last—thank heaven!—let the matter go.

Oh the irony! For it seemed, after all, it was an easier thing for her to do than for him. Abbie continued on with her tour of the house, while he stayed behind. He would allow her her privacy. It was her home, after all. But that meant he was left alone with the portrait, and he found, to his dismay, he could not quite keep his attention from it. The image watched him as he lingered behind, observed him as he examined the home Abbie’s mother had chosen over that in which she had been born to reside. He felt a little like an intruder, and the only way to relieve the feeling that she watched him was to watch her in turn. He was occupied thus when Abbie returned.

She greeted him with a questioning look, but said nothing as she stood at the room’s entrance.

“You take after her,” he said. “That was what I meant before.”

She looked at him a moment, creased her brow and crossed the room to place yet another book and a few photographs inside one of the crates, and then to cover them with protective straw.

“My brother . . .” he began but stopped. Again, some things were better left unsaid, but it seemed she still suspected that his meaning yet disguised an insult.

“Yes, Mr. Crawford? Your brother . . . ?”

“He warned me—”

“Warned you?” She was on the defensive again. He certainly wasn’t doing a very good job of redeeming himself, if that’s what he meant to do. He wasn’t sure he did, after all.

“Yes,” he answered, and tried again. “He said you were uncommonly fair—a stunner, I think, was the word used–” He did not go on, regretted saying anything at all, and rubbed his head in his discomfiture.

She appeared surprised, shocked even, but quickly rallied with a dismissive laugh. “I don’t believe Ruskin said any such thing.”

“Again, you misunderstand me, Miss Gray. It wasn’t Ru—”

“Here!” she said, interrupting him, she retrieved one of the newly placed items from the crate and presented it to him. “My sister doesn’t look so much like our mother as I do, but she is, I believe, what is generally considered very beautiful. There isn’t much comparison.”

He blinked, but his gaze did not leave the photograph. He still felt an idiot for saying anything. “You may be right,” he said in an attempt to lighten the mood, and then glanced to gauge her reaction. It was not what he expected. “I didn’t mean it quite like that. You needn’t cry. Please don’t.”

“It isn’t that at all.” She offered a helpless shrug of her shoulders. “I miss her.”

It was time to go, but he didn’t know what to say. She turned away from him.

“I’ll be outside when you’re ready,” he said and left the house, to sit on a bench in the little garden, and to consider the unexpected results of one afternoon’s sojourn. And to contemplate the little photograph that was still in his hand. That of a fair faced angel. Abbie’s sister. He had somehow forgotten there were two.

Great day, what had he been thinking? That he was going to harm this girl? Make her regret she’d come? Cause her greater misery than she’d so far suffered? He rubbed his face and looked across the Downs. Her land as much as his. He blew a breath of self-chastisement, and patiently continued his wait.

He too was in need of a little quiet contemplation.

If you are interested in more deleted scenes, I’ve reworked the first five, now omitted, chapters of the book into a short story, available at the moment on Amazon and AmazonUK. (It should be free on these websites. If not, try downloading it from here instead.)