The era of instititutionalization

My interest in how society treats its mentally ill and challenged has endured for decades. Publication of Abandoned Asylums of New England: A

Photographic Journey, by John Gray, gave me a chance to reflect again. A highly recommended book, published by the Museum of disABILITY History. Here is my review, which ran in the June 9, 2013, Sunday Providence Journal.

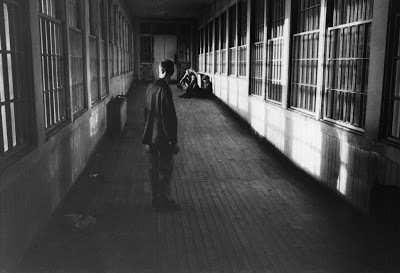

One of the remarkable things about "Abandoned Asylums of New England: A

Photographic Journey" by John Gray is that it makes such a powerful

statement about how society treated some of its most vulnerable members

without using a single image of a person.

Actually, there are

representations of a few people in this extraordinary contribution to

the literature of disability: in a cartoon, an old postcard, a few

vintage photos, and magazine illustrations taped to walls. But that's

it. By focusing on the abandoned buildings where untold thousands of the

mentally ill and mentally challenged (and other vulnerable people)

spent their lives, often neglected and abused, Gray has paid dramatic

testament to forgotten humanity in a way face shots and candids could

not. He has made us see something more haunting: the ghosts of people

who deserved better.

A 1970 Providence Journal investigation, 'The Outlines of a Public

Disgrace,' chronicled warehousing of patients at the now-closed

Institute of Mental Health in Cranston.

Years in the making, Gray's book is

literally an inside look at 12 institutions around the region that now

crumble to dust, or have been razed into oblivion. Their names bespeak

their era, which belongs to the 19th and 20th centuries: Danvers State

Lunatic Hospital; Belchertown State School for the Feeble-Minded; the

Massachusetts Hospital for Dipsomaniacs and Inebriates; the Lakeville

State Sanatorium, for victims of tuberculosis; and eight more.

We

see broken windows, collapsing stairs, peeling paint, a piano with

broken ivories, an open drawer in an old morgue, a dusty laboratory

table with empty vials and jars, mattress-less beds, doors off their

hinges, catacomb-like utility tunnels, a tattered Cabbage Patch doll in a

funhouse-esque corridor, iron lungs, a wooden wheelchair, the skeletons

of birds, and rooms: day rooms, bathrooms, auditoria, solaria, these

places once alive with people. And we see many exteriors: the brick and

stone walls, the Gothic spires, these massive and towering edifices that

contained what were then called lunatics, feeble-mindeds and

consumptives.

Remarkably, too, Gray has found beauty amid the

ghosts that surely roam these grounds. A consummate artist of the lens,

he has given us page after page of black-and-white and color photos that

are rendered masterfully, with exquisite lighting and textures - the

exteriors especially. His twilight shot of the old Danvers hospital

skyline (which, coincidentally, I used to pass every day on my way to

high school), is breathtaking, as are many others. That such beauty

could have countenanced such ugliness is an inescapable irony.

Gray

did not include photos of the two Rhode Island institutions that closed

years ago as treatment shifted to community programs: Exeter's Ladd

Center, and the handful of buildings that are the last vestiges of

Cranston's Institute of Mental Health. But having covered those

institutions years ago for The Providence Journal (indeed, I lived

inside each of them for several days for front-line reporting), I can

assure you that Gray's work speaks for Rhode Island's story, too. And I

would note that it was the power of The Journal's many photos, along

with articles, that helped build public support for more humane options.

Books

like Gray's impress on us the importance of never forgetting.

"Abandoned Asylums" is also a reminder that while community care is an

improvement over institutions such as Ladd and the IMH, society still

has a distance to go in overcoming tired old "retarded" and "lunatic"

stereotypes. It still falls short of the mark in providing better care

for some of our most fragile people, not a few of whom today wrongly

inhabit another institutional system: prison.

G. Wayne Miller

wrote and co-produced "ON THE LAKE: Life and Love in a Distant Place," a

PBS-broadcast documentary film about tuberculosis sanitariums. Visit

him at gwaynemiller.com.

Photographic Journey, by John Gray, gave me a chance to reflect again. A highly recommended book, published by the Museum of disABILITY History. Here is my review, which ran in the June 9, 2013, Sunday Providence Journal.

One of the remarkable things about "Abandoned Asylums of New England: A

Photographic Journey" by John Gray is that it makes such a powerful

statement about how society treated some of its most vulnerable members

without using a single image of a person.

Actually, there are

representations of a few people in this extraordinary contribution to

the literature of disability: in a cartoon, an old postcard, a few

vintage photos, and magazine illustrations taped to walls. But that's

it. By focusing on the abandoned buildings where untold thousands of the

mentally ill and mentally challenged (and other vulnerable people)

spent their lives, often neglected and abused, Gray has paid dramatic

testament to forgotten humanity in a way face shots and candids could

not. He has made us see something more haunting: the ghosts of people

who deserved better.

A 1970 Providence Journal investigation, 'The Outlines of a Public

Disgrace,' chronicled warehousing of patients at the now-closed

Institute of Mental Health in Cranston.

Years in the making, Gray's book is

literally an inside look at 12 institutions around the region that now

crumble to dust, or have been razed into oblivion. Their names bespeak

their era, which belongs to the 19th and 20th centuries: Danvers State

Lunatic Hospital; Belchertown State School for the Feeble-Minded; the

Massachusetts Hospital for Dipsomaniacs and Inebriates; the Lakeville

State Sanatorium, for victims of tuberculosis; and eight more.

We

see broken windows, collapsing stairs, peeling paint, a piano with

broken ivories, an open drawer in an old morgue, a dusty laboratory

table with empty vials and jars, mattress-less beds, doors off their

hinges, catacomb-like utility tunnels, a tattered Cabbage Patch doll in a

funhouse-esque corridor, iron lungs, a wooden wheelchair, the skeletons

of birds, and rooms: day rooms, bathrooms, auditoria, solaria, these

places once alive with people. And we see many exteriors: the brick and

stone walls, the Gothic spires, these massive and towering edifices that

contained what were then called lunatics, feeble-mindeds and

consumptives.

Remarkably, too, Gray has found beauty amid the

ghosts that surely roam these grounds. A consummate artist of the lens,

he has given us page after page of black-and-white and color photos that

are rendered masterfully, with exquisite lighting and textures - the

exteriors especially. His twilight shot of the old Danvers hospital

skyline (which, coincidentally, I used to pass every day on my way to

high school), is breathtaking, as are many others. That such beauty

could have countenanced such ugliness is an inescapable irony.

Gray

did not include photos of the two Rhode Island institutions that closed

years ago as treatment shifted to community programs: Exeter's Ladd

Center, and the handful of buildings that are the last vestiges of

Cranston's Institute of Mental Health. But having covered those

institutions years ago for The Providence Journal (indeed, I lived

inside each of them for several days for front-line reporting), I can

assure you that Gray's work speaks for Rhode Island's story, too. And I

would note that it was the power of The Journal's many photos, along

with articles, that helped build public support for more humane options.

Books

like Gray's impress on us the importance of never forgetting.

"Abandoned Asylums" is also a reminder that while community care is an

improvement over institutions such as Ladd and the IMH, society still

has a distance to go in overcoming tired old "retarded" and "lunatic"

stereotypes. It still falls short of the mark in providing better care

for some of our most fragile people, not a few of whom today wrongly

inhabit another institutional system: prison.

G. Wayne Miller

wrote and co-produced "ON THE LAKE: Life and Love in a Distant Place," a

PBS-broadcast documentary film about tuberculosis sanitariums. Visit

him at gwaynemiller.com.

Published on June 10, 2013 04:38

No comments have been added yet.