What writers can learn from filthy roleplayers

It’s been thirty years – holy crap, thirty years – since I found a copy of Basic D&D in the local gift shop. I’d seen ads for it in the back of X-Men comics and wanted to find out what it was, so I bought it with my birthday money and spent the next week trying to figure it out.

Now, after a hundred campaigns, a thousand sessions and about a million words in various sourcebooks, I still don’t know whether I’ve truly figured roleplaying games out. But I’ve enjoyed trying, and that’s the main thing.

Thirty years is also about how long I’ve been writing fiction, all the way back to my first SF story written at age 12 – and, setting the stage for my entire career, handed into my teacher long after it was due. So for me those two pursuits have run in parallel almost my whole life. My writing informs my gaming, mostly in how I approach plotting and in the language I use when GMing; listen to me run a game and you hear the same turns of phrase that pepper my fiction. But gaming has also informed my writing, because there’s a lot that writers can learn from playing and running games.

What you can’t learn from gaming, just to be clear, is how to write well – decades of gaming fiction have proven that. While there are rare writers who bring style and craft to gaming fiction, like Greg Stolze or Don Bassingthwaite, the vast majority of it is workmanlike at best and utterly dreadful at worst. Hell, Gary Gygax invented the whole damn hobby, but look at his Gord the Rogue books – or better yet, don’t, because they’re terrible. Really fucking terrible. Like a whole new level of terrible 1d6 layers below the regular terrible of other game novels and patrolled by wandering 3d8 awfuls all armed with +3 glaive-guisarmes of suck.

What you can’t learn from gaming, just to be clear, is how to write well – decades of gaming fiction have proven that. While there are rare writers who bring style and craft to gaming fiction, like Greg Stolze or Don Bassingthwaite, the vast majority of it is workmanlike at best and utterly dreadful at worst. Hell, Gary Gygax invented the whole damn hobby, but look at his Gord the Rogue books – or better yet, don’t, because they’re terrible. Really fucking terrible. Like a whole new level of terrible 1d6 layers below the regular terrible of other game novels and patrolled by wandering 3d8 awfuls all armed with +3 glaive-guisarmes of suck.

Well. Maybe not that much. But lord, they’re not good.

But what you can learn from roleplaying games – especially the new breed of drama-focused indie games (but also from plain ol’ D&D and its kin) - is how to tell a coherent, engaging story, along with a few tools that can carry across to telling stories in prose. And tonight, prompted by a suggestion by my mate Dan a while ago, I want to look at some of those things.

Distinctive characters…

One of the great challenges of gaming is reconciling the creative and aesthetic visions of everyone involved, and nowhere is that more apparent than when the players create their characters. But that process also ensures that each of the player characters comes from a different place and sensibility, making them distinct and unique, portrayed with different voices and styles – and equipped with distinct, different abilities. Run a session of a game, any game at all, and you’ll see those disparate ideas come together and find an equilibrium, one where each character is immediately identifiable and has a different set of tools for shaping play. This doesn’t mean you should outsource the creation of your novel’s characters to other people, of course; instead, focus on creating characters that aren’t all cut from the same mold, that have different priorities and purposes in their conception, their interactions with the story and what they can achieve.

…with meaningful abilities

The other good thing about character creation in RPGs is that it delineates what a character can actually do. In some games this is very rigidly and ‘realistically’ defined, outlining exactly how much a character can lift/learn/stab; in others it’s more narrative and handwavey, broadly outlining an archetype or describing the strength of their relationships. No matter the approach, though, all games find a way to define the things that are important in play and then shape the characters so that they interact with those things. This means that players produce characters that can attempt to solve conflicts in different ways and that those ways can all be useful and meaningful in some way. That’s an excellent set of priorities for fiction writing – make sure that the different things characters do all have some impact on the story, even if not in every scene, and that they align with the themes and motifs that you’re trying to define as important in the narrative.

Pacing

Oh god, there is nothing so important and vital I have learned from gaming as pacing, and I have learned it the hardest way possible – by boring the shit out of my players. Whether it’s four-hour combat scenes where hit points are slowly ground away, shopping scenes where some players weigh up the merits of equipment while others drink all the beer in the house, conflicts that are rushed through so people can catch the last train home or just playing out situations that no-one gives a shit about, I’ve made every pacing mistake there is to make. And I’m glad, because I have passed through the fire and burned away my flaws (and possibly my eyebrows). There is a rhythm and flow to pacing, to compressing the dull-but-necessary bits and expanding out the thrilling bits while making sure they stay thrilling, and nothing teaches this to you like your small audience showing its displeasure or engagement by paying attention or falling asleep. And all of that translates directly to prose writing.

Scene framing

This is a vital pacing tool, but it’s also important enough to the narrative to warrant a special mention. ‘Scene framing’ is the simple act of setting a scene for play – deciding on the environment, situation and stakes and then determining the characters’ involvement. Depending on the game, it can be a naturalistic outcome of events – ‘you open the door and there are six demons playing poker’ – or a cut to a new situation ‘it’s two weeks after your wife left you and you come home to find the cat on fire’. Good, assertive scene framing is important because it a) sets up a scene for immediate conflict, b) trims away all the narrative fat from before the scene to focus on the core, which is good for pacing, and c) gives every character in the scene a hook or purpose for being there, which can come from the player or from the GM. Using these principles to set scenes makes for engaging play – and for engaging reading when you carry the same approach over to fiction.

Engaging conflicts

I know I keep saying this, but drama is all about conflict, and RPGs are great at conflict. Admittedly, most of them focus on one kind of conflict, which is the punching/shooting/swording etc kind. RPGs started life as a spin-off from wargames, and that legacy is why many games have a 60-page chapter of combat rules and four paragraphs on how to talk to people to get what you want. But all kinds of conflicts come up in games, and many games have systems or frameworks for exploring them in an enjoyable way. More importantly, RPGs are about pushing conflicts to find some kind of concrete outcome, from killing the troll to convincing the sheriff of your innocence, and it’s wanting to find what that outcome will be that keeps players engaged rather than seeing the whole thing as a speedbump – and the same goes for fiction readers. Some indie games go so far as to set explicit stakes before gaming through a conflict, which is something worth considering for your fiction – but then again, the naturalistic approach of ‘person left standing at the end decides what happens next’ can also make for strong writing. What really matters is that the conflict is meaningful to the characters and the outcome is in doubt; that’s what keeps people reading.

Exploring consequences

And what are the outcomes of the conflict? How do they shape the story that follows? Actions have consequences, and pretty much every RPG is based around following the track of those consequences. A linear dungeon crawl still works its way through a chain of consequences, be it ‘we beat the dragon, took its treasure and spent it on booze and a helm of alignment change‘ or ‘we all got killed by goblins and now the village is on fire’. A twisty, intricate urban horror fantasy might juggle a dozen subplots, but the overall progression of the game will still hinge on how the outcome of one plot has a knock-on effect on another and then feeds into a third, a fourth, a tenth. A dull conflict is one whose outcomes don’t go anyway, like a ‘trash mob’ fight in an MMO; a good conflict is one where the consequences shape play a dozen sessions later, even if only in a minor way. And it pretty much goes without saying that this same principle applies to fiction; that the seeds sown by the very first situation are reaped (along with many others) at the end of your book.

–

Huh. Usually I manage to include more (allegedly) humourous asides in these posts. Guess I have my serious pants on tonight.

There are other tools that can come across from gaming – world-building is a big part of game design, and a lot of that translates well to doing the same in prose – but these are the big ones for me. More pertinently, these are ones that come out in actual play, rather than the planning stages, and ones that get honed and refined the more actual game playing or GMing you do.

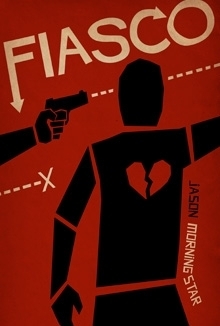

And because of that, these are tools and skills that you learn by doing – the best, the only way to pick up the strengths of gaming and bring them to prose writing is to get in there and play or run a game (and preferably a lot more than one). If you’ve not tried roleplaying but you’d like to give it a try and see what you learn, there are a number of fantastic games out there that can demonstrate all the things I’ve been talking about – check out Dungeon World, Fiasco, Smallville (yes, really), the various World of Darkness games, Don’t Rest Your Head, Fate Core or Fate Accelerated, Mutant City Blues or straight-up Dungeons & Dragons (4th edition is my favourite). All of these are great games that showcase some or all of the concepts I’ve been talking about.

And because of that, these are tools and skills that you learn by doing – the best, the only way to pick up the strengths of gaming and bring them to prose writing is to get in there and play or run a game (and preferably a lot more than one). If you’ve not tried roleplaying but you’d like to give it a try and see what you learn, there are a number of fantastic games out there that can demonstrate all the things I’ve been talking about – check out Dungeon World, Fiasco, Smallville (yes, really), the various World of Darkness games, Don’t Rest Your Head, Fate Core or Fate Accelerated, Mutant City Blues or straight-up Dungeons & Dragons (4th edition is my favourite). All of these are great games that showcase some or all of the concepts I’ve been talking about.

Hell, if you live in Melbourne and you want to give ‘em a try, leave a comment. I can always do with more players.

(And if you’re interested in reading more about my gaming adventures and ideas, check out my gaming Tumblr Save vs Facemelt and the ongoing story of my D&D campaign Exile Empire over at Obsidian Portal.)