Andrew Jackson and the Central Bank

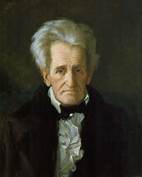

Andrew Jackson, 7th U.S. president

Can you imagine a president taking on the Federal Reserve System today? That’s what Andrew Jackson did in 1832, and it changed America forever.

The Hydra-Headed Monster

In the early 19th century, the forerunner to the Federal Reserve was the Second Bank of the United States. President Andrew Jackson despised the Bank, ostensibly because it held too much power over the economy, but truly because it was controlled by his political enemies. So Jackson set out to destroy the Bank.

The Bank had been created in a desperate attempt to stop the high debt and inflation caused by the War of 1812. However, the Bank only made matters worse by printing its own currency and extending generous (and sometimes fraudulent) loans to political friends. The loans helped cause an economic boom that crashed with the Panic of 1819, the first depression in American history. The depression soon ended, but many never forgot the Bank’s role in the crisis.

In the 1820s, the Democratic Party was formed, supposedly to represent working class voters, many of whom resented institutions that catered to the rich such as the Bank. Jackson became the first Democratic president in 1829, and he joined in on the class warfare by calling the Bank “a hydra-headed monster… it impaired the morals of our people, corrupted our statesmen, and threatened our liberty. It bought up members of Congress by the Dozen… and sought to destroy our republican institutions.”

Many perceived Jackson’s opposition to the Bank as an effort to keep government limited, to restore a sound financial system, and to free the “common man” from control by “monied elites.” However, Jackson was not opposed to central banking in general, rather he was opposed to the Bank because it was controlled by his political enemies, among them Bank President Nicholas Biddle.

Biddle and the National Republicans

Biddle routinely used lending practices for political gain, including using Bank funds to publish newspaper attacks on opponents. Biddle openly favored the National Republicans (later to become the Whig Party), many of whom benefited financially from Biddle’s favor. Prominent National Republicans were Congressmen Daniel Webster (who was on the Bank’s payroll as a legal counsel) and Henry Clay (Jackson’s opponent in the 1832 presidential election).

Demonstrating general support for central banking, Jackson offered a compromise in which the Bank would remain in operation in exchange for diminishing its power. However, Clay and Webster advised Biddle to reject the compromise because the Bank had enough support from Congress to continue operating without having to decrease its power.

To secure the Bank’s position, Clay convinced Biddle to petition Congress for re-charter in 1832, four years before the Bank’s 20-year charter was set to expire. Clay guessed that Jackson would not dare risk losing reelection by vetoing the Bank’s charter. Clay guessed wrong.

The Alarming Veto

In a strong and unprecedented veto, Jackson cited several reasons for refusing to re-charter the Bank:

It was a dangerously centralized financial power

It held an unconstitutional monopoly on finance that only helped the rich get richer

It made the economy vulnerable to foreign and special interests

It held too much influence over federal politicians

It favored the North (where most financial centers were located) over the South and West

Jackson also declared that an investigation had revealed that the Bank attempted to influence elections through fraud. He stated, “If (government) would confine itself to equal protection… it would be an unqualified blessing. (Re-chartering the Bank) seems to be a wide and unnecessary departure from these just principles.” Congress could not muster a two-thirds majority to override Jackson’s veto.

The veto was highly controversial because it was the first to use political, not just constitutional, reasons for its application. This set a precedent for future presidents to follow, which gradually expanded the power of the Executive branch of government.

“King Andrew”

National Republicans were outraged. Biddle called the veto a “manifesto of anarchy,” and Webster called it a “political tool.” Other Bank supporters denounced “King Andrew’s” tyrannical use of veto power. Meanwhile, the Bank directly contributed $100,000 to Clay’s presidential campaign and indirectly controlled thousands of potential voters through political favors.

Jackson’s opponents distributed his veto message in an effort to discredit him. However, they underestimated public resentment toward the Bank, and Jackson easily defeated Clay in the 1832 election. Upon winning a second term, Jackson pressed his advantage by ordering the withdrawal of federal funds from the Bank’s vaults. Jackson fired two Treasury secretaries before finding someone—Roger B. Taney—who carried out his order. Taney was later appointed Chief Justice of the U.S. as a reward for his loyalty.

Removing federal funds essentially killed the Bank by depriving it of the capital needed to extend loans and favors, which was its primary advantage over competitors. Jackson ordered the deposit of federal funds into state banks friendly to the Democratic Party, which were derisively called “pet banks.” The Bank of the United States sputtered along until its charter expired in 1836. Jackson’s victory was complete.

The Censure

Realizing that it was no longer the most powerful branch of government, Congress responded by censuring Jackson for assuming “upon himself authority and power not conferred by the Constitution and laws.” Shortly before Jackson left office in 1837, a more sympathetic Congress removed Jackson’s censure from the record.

Jackson’s victory over the Bank decentralized the economy and led to greater economic prosperity and individual freedom through the 1840s and 1850s. However, his devotion to patronage (i.e., granting jobs to political allies) doubled the size of the federal government during his term, which centralized political power in Washington at the people’s expense. This chipped into the prosperity and freedom generated by the end of central banking.

In the end, the central bank returned in the form of the Federal Reserve, and the size of government has increased to record levels, partly thanks to Jackson’s precedent. So individual liberty ultimately lost on both counts.