The Shot Heard ‘Round the World – Lexington and Concord and the Start of the American Revolution

Please help me in welcoming Dr. Stanley Carpenter. Below is his article about the battle that started not only the American Revolutionary War, but my book, the Battle of Lexington-Concord. Yes, I’m hopelessly plugging my book. But just bear with me please. Violet, my protagonist, not only witnesses the shootout at the Old North Bridge, but eventually grabs her own musket and participates. So this article is one that I’m very grateful to add to my blog, but also to read over and understand just where some myths come from, and how some mysteries of that war will never be solved. So without further ado . . . here is a snapshot of the Battle of Lexington-Concord by Dr. Carpenter!

The Shot Heard ‘Round the World – Lexington and Concord and the Start of the American Revolution

Prof. Stanley D.M. Carpenter, US Naval War College

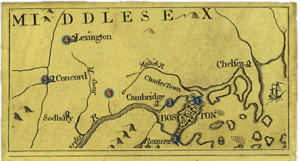

Faced with the threat of potential violence from the increasingly hostile local population, Major-General Thomas Gage, Crown Commander-in-Chief in North America, having received reliable intelligence that the local Massachusetts Bay militia groups known as “training bands” had gathered and stored arms, powder, and other weaponry in Concord, Massachusetts (northeast of Boston), ordered Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Smith to march 700 troops from Boston on the morning of 19 April 1775 to capture or destroy the military supplies.

At 0300, Smith sent Major John Pitcairn ahead at a quick march with six companies of Light Infantry, which arrived at Lexington Commons about sunrise. Set in motion by instructions received 14 April 1775 from Secretary of State for the Americas, the Earl of Dartmouth, to disarm rebels and arrest leaders after a series of largely bloodless clashes called the “Powder Alarms,” Gage resolved to take positive action. But, from agents in London, the colonists already knew of the orders and, alerted the night before of the British movements by fast riders, the militia started to gather.

As the first three companies of Light Infantry arrived on Lexington Commons and formed up (with the main body still down the road towards Cambridge) seventy-seven Lexington militiaman commanded by Captain John Parker exited Buckman Tavern and lined up on the Commons. Legend has it that Parker exclaimed to his men: “Stand your ground: don’t fire unless fired upon, but if they mean to have a war, let it begin here.” Either Pitcairn or another officer rode forward and ordered the colonials to disperse, shouting “lay down your arms, you damned rebels.” Although Parker then ordered his men to stand down, none laid down their arms. Both Pitcairn and Parker ordered their men to hold their fire, but a single shot set in motion the ensuing chaos. Various theories abound, including a shot from the second floor of Buckman Tavern or from behind a hedge or from a mounted British officer, possible Pitcairn. Sporadic firing erupted from both sides. As the British troops advanced with bayonets, the militiamen fled. One soldier of the 10th Regiment of Foot suffered a slight would, but eight militiamen died in the melee with a further ten wounded.

Hearing the gunfire, Smith hurriedly rode forward. With the beating of Assembly, he re-organized his column and marched northwest towards Concord. As the regulars approached Concord, roughly 250 militiamen formed up to block the passage; realizing the numbers disparity, the militia under Colonel James Barrett abandoned the town and retreated to the Old North Bridge a mile from Concord as militia from more westerly towns started to arrive.

In town, the Grenadiers of the 10th Regiment secured the South Bridge while the Light Infantry occupied North Bridge as the troops began a thorough search for arms. Amazingly, the regulars found three 24-pounder cannon buried at Ephraim Jones’ Tavern. The soldiers smashed the gun carriages and tossed 550 pounds of lead musket balls into a millpond. Troops paid for the food and drinks from the locals even while they were being misdirected as to the location of additional arms and powder. Tragically, a fire set to burn additional gun carriages set afire the town Meeting House and the soldiers formed a bucket brigade. Seeing the smoke, Barrett’s men hurried back towards Concord and established a position near the North Bridge as militiamen from Acton, Concord, Bedford and Lincoln arrived.

Severely outnumbered, the troops holding the North Bridge fell back with militia in pursuit. Captain Laurie formed the two Light Companies into ranks to defend the bridge, but sporadic firing broke out from both sides as officers and non-commissioned officers sought to restore order and discipline.

On the militia side, Barrett regained control and moved his men 300 yards back up the hillside as Smith assembled two companies of Grenadiers to reinforce Captain Laurie. Meanwhile those soldiers that had searched Barrett’s farm returned and the firing ceased. The soldiers, watched carefully by the militia, completed the search, ate lunch, and formed up for the march back to Boston with their mission completed. But, as the formation moved across the Bridge, Reading militiamen opened fire. With ammunition low and many officers, including Lieutenant-Colonel Smith (wounded in the thigh) felled by the musketry, the march back became a nightmare for the relatively inexperienced British soldiers. Many casualties occurred as the militiamen in a running battle, fired from behind stone fences and trees, thus originating the mythology of colonials firing from behind rocks and trees at marching formations on the road. This type of action occurred only once in the ensuing war – at the march back from Concord.

By early afternoon, a 1,000-man relief column under General, the Earl of Percy arrived with several Regimental Battalion Companies. They encountered Smith’s Grenadiers and Lights, who appeared disorganized, ragged and dazed. Percy opened fire with artillery that dispersed the militia. He set up a hasty field hospital at the Munroe tavern to treat the wounded and after a brief pause, began the march back to Boston. The “run and gun” engagement continued once the artillery ceased fire. With flankers out to disrupt snipers and wagons carrying wounded in the center of the column, the march to Boston encountered a number of small skirmishers. With far greater numbers, the rebels lined the route of march to snipe at the retiring British troops. As the column reached Menotomy, house to house street fighting broke out as soldiers flushed out snipers posted in homes and commercial buildings.

By evening the battered British force reached the safety of Boston, but with heavy casualties. As many as 15,000 colonial militia had taken part in the engagements with forty-nine killed, thirty-nine wounded and five missing, presumed dead. On the Crown side, seventy-nine British soldiers died with 174 wounded and over fifty missing, presumed dead. The actions at Lexington and Concord sparked off an active and violent rebellion that only ended with the surrender at Yorktown, Virginia of Lieutenant-General Charles, Earl Cornwallis in October, 1781 to the Combined Franco-American armies. The actions at Lexington and Concord on 19 April 1775 prompted George Washington to exclaim that the “once happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched in blood or inhabited by slaves. Sad alternative! But can a virtuous man hesitate in his choice.”