The author and the playwright

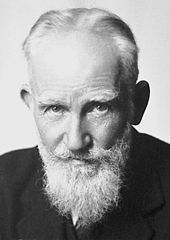

I began my writing life as a scriptwriter. There are advantages to starting out this way. The scriptwriter creates his or her characters entirely through dialogue and, unless he wants to seriously annoy his actors (or he is Bernard Shaw), he will avoid describing his characters’ characteristics, physical or otherwise, or how a line should be delivered, in the stage directions.

Bernard Shaw, not known for his economy, though a remarkable playwright and man

What’s more the scriptwriter understands economy: she/he knows that every word in a play has to earn its keep so he/she is less likely to over-explain the characters or their background, or tell the audience or viewer what to think (unless he is Bernard Shaw). And since drama is a collaborative affair the script the writer delivers may well undergo such radical change through the actors’ (and others’) interpretation that the finished product is almost unrecognisable. Moreover again, as the continuing legacy of our ‘classic’ playwrights such as Shakespeare, Ibsen, Chekhov etc have proven, there is more than one way to pay Hamlet, or Nora, or Uncle Vanya.

Anton Chekov, master of mockery

The author on the other hand has complete control over his work, if not how it is interpreted. When I turned to writing books rather than scripts, which I did only comparatively recently, I came up against the challenge of Description. In a play all you have to say to describe your setting is something like ‘A bedsitting room: two doors, one L one R, sofa DR, two chairs, table C, window UC, and a general feeling of chaos’; but in books the writer is expected to paint pictures in words, eloquently and evocatively – a problem I found irksome not only because I’m not very adept at writing description but because I kind of expected the reader to supply their own pictures from their imagination, as they would for instance in a radio play; which turned out to be not totally satisfactory, or so I was told.

But the thing I found most difficult of all - other than the old old problems of ‘he said, she said’ etc – was the rhythm of a dialogue scene. In a script if you want a pause you can simply write ‘pause’, or perhaps ‘silence’, or even at a pinch ‘beat’, or – if you’re Harold Pinter – ‘…’; all of which mean different things.

In a book you’ve got to find another way. You can say ‘there is a pause’, or even ‘there is a silence’, and ‘he/she doesn’t reply’, but you can’t keep doing that all the time. Early on in my book there’s a scene where the erudite, wealthy and urbane George Matcham (Nelson’s brother in law) pays a visit to his cousin Mary Pitt to put to her the proposal that she emigrate to New South Wales. In order to indicate a lull in the conversation, after I’d exhausted all the ‘pauses’ and ‘silences’ I had Mary staring into the middle distance, or George crossing his legs, or tugging at his waistcoat, or leaning forward on his chair. When I read the scene back I realised he’d crossed his legs so often he’d turned – as a friend of mine (not a writer) eloquently described – into a pretzel. And he’d lent forward so much he’d have tumbled right off the chair. I think that one scene took me as long to write as an entire full-length play.

There’s no question which is the easier thing to write. There are some authors who can churn them out in a few weeks, but generally speaking you’re talking of months, or even years, to produce a book; whereas some playwrights – notably Noel Coward and Alan Ayckbourn – allegedly have written plays over a weekend.

Alan Ayckbourn

Noel Coward

So why is it that there while there seems to be no shortage of really readable new books being published that there are so few really watchable new plays?