On choice architectures

Yesterday Andrew Vanden Bossche posted a great article called The Tyranny of Choice in response to the formal questions about narrative that were in my post A Letter to Leigh.

In the article, Andrew argues that every system by its very nature is a statement, not a dialogue. After all, if we artificially control the boundaries of the system, then every system imposes a worldview. (This is the same argument made about how the original SimCity espoused liberal politics through its simulation).

There are not some games that subvert player agency, and others that grant it. Rather, all games, by nature of being games, by nature of being systems, inherently restrict player agency in the exact same ways. The difference between the games with this “aesthetic of unplayability” (as Koster calls it) and any other game is nil. Other games are merely better at hiding their true nature.

…I question whether there is a difference at all between this games that subvert and refuse player agency and those that encourage and celebrate it. I wonder whether player agency, as we know it, this quality we assume games just naturally have, is actually an illusion. Koster implies that games are capable of create dialogue with their systems; I believe games can only make statements.

This led to a great little discussion with Andrew and also with Andrew Doull, which I have captured as a Storify post here.

It led me to think a bit about architectures of choice. As Andrew Vanden Bossche put it, “if a ‘fake’ choice is as meaningful as a ‘real’ one, is there a difference?”

These are all matters of degree, of course. A work is built out of many moments of interaction (and lack of interaction). A given moment may have immense freight of meaning carried by qualities other than the choice architecture (graphics, storytelling, words, music, and so on).

A long time ago, I did a presentation about two models for thinking about narrative in games. One is the impositional narrative, the case where the author is imposing a worldview firmly on the player. The other is the expressive narrative, where the player imposes a worldview on the system, within the system’s limits. We can also think of these as the narrative created a priori and the narrative created post facto, as storytelling versus mythologizing, as plot versus memory. (Later this was developed into a much more robust framework called the storytelling cube; alas, this presentation requires IE to view right now).

I agree with Andrew that games are always statements. But emergence, user-generated content, chaotic systems, and yes, even our universe are also systems, and they are systems rich enough to allow for what I would personally term dialogue within a system – even if those systems are limited in ways that convey a message. I say that based on my experience creating emergent systems in online worlds, where players continually surprised me by responding to and with the system in ways that I certainly did not foresee. In effect, they expanded the boundaries of the system themselves.

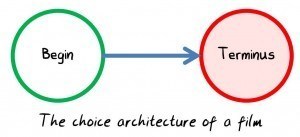

A whirlwind tour of choice architectures might start with a film. The viewer does always have more choice than shown in this diagram, of course; they can get up and leave, they can throw popcorn at the person in front of them, they can shout “fire!” in the theater. But we can think of these as both always-present and un-architected choices. They are all essentially forms of breaking the contract between the viewer and the filmmakers.

Really, what you are “supposed” to do is sit back and absorb. There’s plenty of room for interpretation here, of course, but on a semantic level, not a systemic level. The systemic level does not admit of choices.

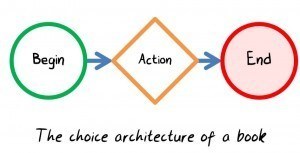

A book is somewhat more interactive. You have to turn a page. But it really doesn’t matter how you turn the page, you’re going to get to the same place. Again, the individual’s experience along the way may be very different thanks to other media, but the systemic artifact itself is very simple, and not particularly open to interpretation.

A book is somewhat more interactive. You have to turn a page. But it really doesn’t matter how you turn the page, you’re going to get to the same place. Again, the individual’s experience along the way may be very different thanks to other media, but the systemic artifact itself is very simple, and not particularly open to interpretation.

There have been efforts to change this. Alain Robbe-Grillet write in an intentionally fractured style. Ezra Pound basically pushed the equivalent of hypertext links on readers of his poetry. Carolivia Herron’s Thereafter Johnnie suggests in its text an alternate order in which to read the book. Julio Cortázar’s novel Rayuela (translated as Hopscotch) plays with the actual form:

An author’s note suggests that the book would best be read in one of two possible ways, either progressively from chapters 1 to 56 or by “hopscotching” through the entire set of 155 chapters according to a “Table of Instructions” designated by the author. Cortazar also leaves the reader the option of choosing his/her own unique path through the narrative.

This is also not dissimilar to the QTE in games; after all, the price of failure on a QTE is generally a sudden death moment, the end of a story. It is a degenerate narrative, one where it is clear that going on is the main current.

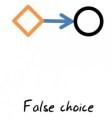

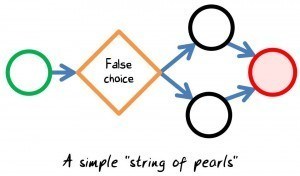

A very common way of dealing with the issue of agency in AAA games is to use the narrative structure termed “string of pearls.” In its simplest form, this is providing the player a number of choices in how to resolve a situation, but collapsing all those choices down to one actual consequence (usually, success in getting past an obstacle). This allows the player to feel real agency moment to moment, while retaining control of the story in authorial hands.

A very common way of dealing with the issue of agency in AAA games is to use the narrative structure termed “string of pearls.” In its simplest form, this is providing the player a number of choices in how to resolve a situation, but collapsing all those choices down to one actual consequence (usually, success in getting past an obstacle). This allows the player to feel real agency moment to moment, while retaining control of the story in authorial hands.

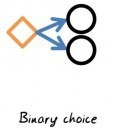

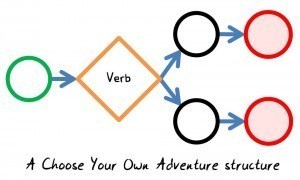

Multiple endings puts a structure in the realm of the Choose Your Own Adventure. Here is the first time we see choices having actual consequences, which also means it is the first time that the author is ceding consequential control to the player. Here for the first time the player constructs not only their own narrative, but their own story. Of course, it is within a rigid structure still, and every possible story has been planned out in advance by the author.

Multiple endings puts a structure in the realm of the Choose Your Own Adventure. Here is the first time we see choices having actual consequences, which also means it is the first time that the author is ceding consequential control to the player. Here for the first time the player constructs not only their own narrative, but their own story. Of course, it is within a rigid structure still, and every possible story has been planned out in advance by the author.

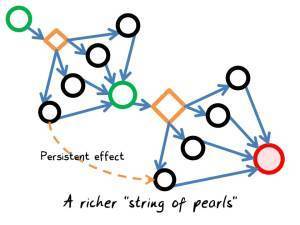

The modern AAA game is actually more a hybrid of “string of pearls” and CYOA. In more complex forms of “string of pearls,” we see that the choices within the “pearl” can be quite rich. But the system still narrows down repeatedly to choke points, where previous choices are shown to have little consequence. In the best games that use this structure, such as Dishonored, there are long-term effects from making choices within the pearl, that manifest as ripple effects as you advance through the game (often presenting the player with multiple endings). But again, at the higher level of structure, the endings are pre-written, and the player is usually being given a binary choice, or perhaps a few choices of endings.

The modern AAA game is actually more a hybrid of “string of pearls” and CYOA. In more complex forms of “string of pearls,” we see that the choices within the “pearl” can be quite rich. But the system still narrows down repeatedly to choke points, where previous choices are shown to have little consequence. In the best games that use this structure, such as Dishonored, there are long-term effects from making choices within the pearl, that manifest as ripple effects as you advance through the game (often presenting the player with multiple endings). But again, at the higher level of structure, the endings are pre-written, and the player is usually being given a binary choice, or perhaps a few choices of endings.

In Colossal Cave there is a famous puzzle where you have to kill a dragon. You try every object you have: a sword, a knife, a bird… nothing works. If you just try KILL DRAGON, the game snarkily replies “With what, your bare hands?”

The answer to the puzzle is, of course, “YES.”

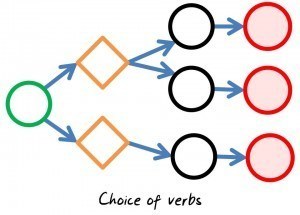

The dividing line between ludic artifact and branching story may lie in the distinction between a choice and a verb. Enabling players to choose not between “means of killing” but between “killing” and “befriending” is where richness really starts to come in, and where the best AAA games operate today. I have to think on this more, but in game grammar terms, a given game atom or ludeme (pick your term!) is recursive, it nests. So something like “kill” is in itself “a game” in the sense that it is a ludic artifact itself, capable of being extracted from the larger system and played on its own.

The dividing line between ludic artifact and branching story may lie in the distinction between a choice and a verb. Enabling players to choose not between “means of killing” but between “killing” and “befriending” is where richness really starts to come in, and where the best AAA games operate today. I have to think on this more, but in game grammar terms, a given game atom or ludeme (pick your term!) is recursive, it nests. So something like “kill” is in itself “a game” in the sense that it is a ludic artifact itself, capable of being extracted from the larger system and played on its own.

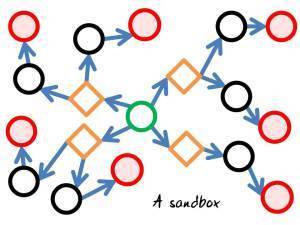

A sandbox game, like The Sims (the original), Grand Theft Auto, Ultima Online, or Minecraft, offers a profusion of verbs at any moment, and has very little authorial push down a single path. Rather than proceed linearly, it sprawls like a jellyfish dropped on concrete (and is often just about as coherent). Players are now much more in the authorial role in that they truly are driving both narrative and story here.

A sandbox game, like The Sims (the original), Grand Theft Auto, Ultima Online, or Minecraft, offers a profusion of verbs at any moment, and has very little authorial push down a single path. Rather than proceed linearly, it sprawls like a jellyfish dropped on concrete (and is often just about as coherent). Players are now much more in the authorial role in that they truly are driving both narrative and story here.

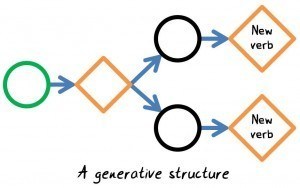

Most importantly, it is at the high end of this structure that we find games like most MMOs, Nomic, Calvinball or Dwarf Fortress, where the actions of players do not just result in the system spitting back a bit of static content, but completely new verbs that exist only because the player put them there. In effect, games where the players create new rules, usually through programmability, emergent behavior, and user-generated content. Now we are in the realm of games where it is the player who makes the art.

Most importantly, it is at the high end of this structure that we find games like most MMOs, Nomic, Calvinball or Dwarf Fortress, where the actions of players do not just result in the system spitting back a bit of static content, but completely new verbs that exist only because the player put them there. In effect, games where the players create new rules, usually through programmability, emergent behavior, and user-generated content. Now we are in the realm of games where it is the player who makes the art.

Now, all the above is excessively reductionist. For example, not all verbs are created equal.

Some verbs are structurally false choices even though they have the trappings of great consequence; a QTE might be one such. We might think of this as the equation “2 = 2.” These sequences evaluate to “true.”

Some verbs are simple binaries, such as the choice to choose a moral path through conversations in an RPG. A great profusion of choices, still narrowed down to a binary outcome. We might think of these as Boolean equations.

Other verbs are applicable to a very wide array of situations and choices. “Kill” in an RPG is one such, and because it is a ludic system in its own right, it operates much like an algorithm into which you can feed different values, sort of a finite state machine.

Given a rich enough possible array of outcomes, the player may perceive this actually finite set of possibilities as infinite. At that point, perceptually, it becomes an analog system, not a digital one. And herein lies ambiguity, interpretability, and so on, because in systemic terms, perceived problem complexity is the path towards fun (cf Games Are Math).

For me, the question of what makes systems richly interpretable – as opposed to their dressing in the form of words, art, and music – is an interesting and important one. We have a lot of history and tradition in making words richly interpretable, music richly interpretable, art richly interpretable. It’s not a solved problem, by any means, but it is relatively solved. On the other hand, we don’t have a lot in terms of systems as constructed ludic artifacts.

One way to think of this is on the scale of representational to abstract; a representational artwork imposes more on the viewer. An abstract one invites the viewer to contribute more. Similarly, different choice architectures invite different sorts of contributions from the player. In a linear work, there is lots of room for the reader to interpret what is there; in a non-linear work, there is more room for the player to interpret simply because of what is not there. In game grammar terms (PDF), a game on the lower end of this choice architecture scale might be very deep (chained sequences of choice) but it is not very broad (branching choices).

It is likely axiomatic that structures on the broad end are going to be where richly interpretable systems lie. In other words, where we reach for ludic art.

Learning about color theory, negative space, and line is a key part of art training.

Learning about rhythm divorced from melody, melody divorced from timbre, timbre divorced from harmony is a key part of music training.

Learning about prosody independent of words, plot apart from character, character separate from description, is a big part of learning to write.

The real question is about how we create ambiguity in our work, and it leads to a very personal aesthetic choice: the prickly question of whether a work that accomplishes its effects through ludic systems rather than other media is “better crafted” as a ludic artifact. This says nothing about its merits as a work in totality, but opens up the same sort of question that we ask when we say that a musical has good songs versus relying on its staging and spectacle, that a song has a good melody and a bad arrangement, or whether good acting is carrying a bad script.

In the end, these tools aren’t about which work is brilliant and which is not; it’s about the ways in which they can be brilliant.