Reflections in the Water – A story by David Conway

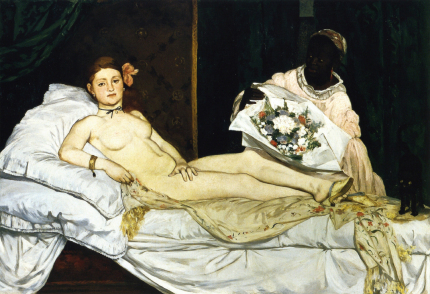

Olympia by Édouard Manet – 1863

In the foreground of the painting a man lounged on a grassy bank while a dog lay sleeping at his feet. He watched a cluster of small boats on a nearby river. The grass was a pale luminous green and the shadows were very clear. Niamh had watched the painter in silence for a while, now she said, ‘The reflections in the water are so gentle, almost imperceptible, but they make the painting true. You don’t have any sketches, how can you do that from memory?’

He did not answer for a while, but continued to paint. Niamh stood behind him and to one side, so that her shadow did not fall across the canvass. It had been a long while since she had come to the Westminster Hotel and spoken to the painters. In the early days she had worked from here herself, and seen them every day. This had been the first idea of hers that had really worked: to hire some of the older rooms to artists at low rentals, or sometimes no rental, and then exhibit their work in the hotel. It had turned the Westminster into an art factory, a place where the guests could see contemporary artists working and interact with them, or buy their work if they want to.

Eventually he said, ‘I do not work from sketches, or photographs, why would I do that?’ He turned and looked at Niamh in a questioning way, and she realised that this was not irony, he was asking innocently, it was the way a child would put a question. He had wide brown eyes that seemed to fill his pale face.

‘You must have an extraordinary visual memory,’ she sad. ‘It’s so complete, so many details.’

His expression did not change. He looked back at his painting, and then he said, ‘I can only paint what I see, but I have to see it for a long time before I start.’

‘When did you see this?’

‘In Ireland, when I was a child.’

‘But you must have been back to this place since?’

‘No, never.’

‘And you can remember it so completely?’

He nodded, as if this was not a remarkable thing.

She said, ‘My name is Niamh Ryan, I bought this hotel a few years ago and renovated it. I always wanted painters to work here, have you been working here for long?’

‘I came here yesterday,’ he said.

‘Well I’m glad you did, how did you hear about us?’

‘I am your cousin.’ Niamh did not react, but noticed that his face remained expressionless. ‘My name is Aaron Ryan. We have the same great grandparents.’

‘If you were my cousin Mr Ryan, or even my second cousin, I would know you.’

He smiled, a gentle reproachful smile, ‘In Ireland, many of us have relations we do not know. There is often a black sheep, someone the family disown.’

‘My grandfather had more than one brother.’

‘That’s right, three to be exact. I am Eamon’s son.’

‘Eamon? But Eamon never told me he had a son.’

‘No, he rarely told anyone about me.’

‘I didn’t see you at his funeral.’

‘No, I wouldn’t have been welcome. My mother didn’t want me there.’

‘I’m stunned, I can hardly believe this. Why did you come here?’

‘A painter can survive in New York a little better than he can in other places.’

‘Did you know that I owned this hotel?’

‘Yes, my father became famous in Ireland when the horses he trained began to win races, and you were his most important owner. Your name is often in the papers.’

‘And that’s why you came here?’

‘No, I came here because I heard that an artist could get a roof and a meal here, and I needed both.’

He turned back to the canvass and began to paint again. He built up colour in tiny dots, gently pricking the canvass with a fine brush.

Niamh said, ‘I thought a great deal of your father, I miss him very much. How did you and he become estranged?’

‘He didn’t want me to be a painter; he wanted me to take over the farm. I was his only son.’

‘But surely that wasn’t a reason for him to disown you?’

‘In his eyes it was a betrayal. He made it clear that if I left home I wasn’t to return.’

‘I can’t believe that.’

‘My father was a more ruthless man than many people realised. His was an iron fist in a velvet glove; I suppose that was why he did so well.’

Niamh met her mother for coffee the next morning. Bridget remembered Aaron, but knew little, ‘Yes, Eamon had a son who left home when he was quite young. Eamon never told us why, it seems there was some kind of argument.’

‘He said it was because he wanted to be a painter.’

‘I don’t know what happened, it just wasn’t talked about.’

‘Has he ever tried to contact you?’

‘No, never. I don’t think he ever tried to contact your father either. Connor never mentioned it.’

‘I wonder why he waited so long to contact me.’

‘From what you tell me, he may not have tried to contact you. It sounds as though he arrived at The Westminster because he wanted to paint there. Perhaps it had nothing to do with you.

‘Perhaps you’re right. Miles is always suspicions of coincidences; he says real ones are rarer than you think.’

‘Where is Miles?’

‘He’s in London, but he’ll be back in New York in a couple of days.’

On the following evening Niamh took Aaron to dinner at l’Atelier, the restaurant of the Westminster Hotel. He ate greedily; like someone who had not had a full meal for several days. He drank a lot too; Niamh ordered a second bottle of wine for him.

‘I can sense you don’t believe I’m your cousin,’ he said. ‘I don’t mind, I am not close to my family.’

‘Why don’t you mind? I can’t imagine anything worse than being rejected by my own family.’

He shrugged, ‘It happened a long time ago, I have learned to live without them.’

‘Do you make money from your paintings?’

‘Sometimes.’

‘You should do, you’re very good. Don’t you have a dealer?’

‘Not anymore. I had one once but he died.’

‘Then we’ll find a dealer for you, and we’ll sell some of your work ourselves.’ He nodded, but made no other reaction. ‘Wouldn’t you like to have a dealer?’ said Niamh.

He nodded again, but in a vague undetermined way. ‘I never get on with dealers,’ he said, ‘I don’t really care about money.’

‘That’s the point of getting you one,’ said Niamh. ‘If you have a god dealer, you won’t have to worry about money, you can just paint.’

Again he nodded and then he said, ‘I want to paint you.’

Niamh smiled, ‘I would like that too, but I’m very busy at the moment. How would you paint me?’

‘I would paint you as Olympia, in the style of Manet.’

Niamh thought for a moment; then she said, ‘But isn’t that painting a nude?’

He nodded, ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘that is how I see you.’

Niamh laughed, ‘Well, I don’t think I’m ready to be painted naked, but I’d like you to paint my portrait. Will you do that for me?’

Miles was sceptical, as Niamh expected. He said, ‘Isn’t there some way you can check, be sure he really is who he says he is?’

‘Not easily, no. Eamon is dead and his wife Cara won’t talk about it. Anyway, I believe him. I can see he is a Ryan, I can see our blood in him.’

‘What does he want from you?’

‘Absolutely nothing, that’s one of the reasons I believe him.’

‘I suppose there’s no harm in him painting your portrait.’

‘No, there isn’t. And stop looking at me as if there is.’

Niamh posed for Aaron sitting in a worn armchair in front of an untidy book case. Aaron painted quickly and said little. She found herself maintaining what was almost a monologue. Then, quite suddenly, he became garrulous.

‘If I had some money I would live by the sea,’ he said, ‘a cottage by the sea, and I would paint the sea in all its moods. If I could do that I would be happy.’

‘Then why don’t you?’ said Niamh. ‘You could make enough money from your paintings to do that.’

He shrugged, ‘Perhaps,’ he said, ‘but I doubt it. I never could before.’

‘But you paint so well.’

He thought for a moment, and then he said, ‘If I could just paint, then perhaps, but to live in such a way that you can paint all the time is a hard thing to do. At least, it always has been for me.’

‘What stops you from painting all the time?’

‘People, problems, sometimes money. All sorts of things. ’

Niamh stood up, put her arms around him and hugged him for a while. Then she said, ‘You are my cousin and I want to help you. We’ll find a cottage for you, close to the sea, and I’ll lend you the money to buy it. You can pay me back when you’ve sold more paintings.’

He pushed her gently away and said, ‘That’s very kind of you, but I can’t let you do that. You hardly know me.’

‘You’re part of our family and that’s good enough for me.’

‘No, a house, that’s too much, I can’t let you do that.’

‘Why not, I insist.’

‘No, it’s too much, but there is something that you could help me with.’

‘What is it?’

‘I owe a man some money, quite a lot of money. I’ve been in debt to him for a while, and he’s pressing me hard. He’s the kind of man who’s difficult to say no to. He’s threatened to hurt me if I don’t pay him back.’

‘Would he really do that?’

‘Yes, I think he would.’

‘How much do you owe him?’

‘A hundred thousand dollars.’

Niamh was silent for a moment, then she said, ‘That’s a great deal of money, how did you get so deeply into debt?’

‘I had a studio for a while, here in New York. He lent me the money to set it up. Things went well at first, but then I got ill and fell behind in the repayments.’

‘Is that all you owe?’

‘Yes, that’s all.’

‘All right, I’ll lend it to you and you can pay me back whenever you want. If you give me your bank details I’ll transfer the money to you tomorrow.’

‘I don’t have a bank account, and anyway, I have to pay him back in cash. He’s not the sort of man who takes cheques.’

‘Cash? Are you sure?’

He nodded, ‘Yes.’

She stood and looked at the painting, which was almost finished. He had caught her likeness perfectly; Niamh’s small round face and bright wide eyes stared back at her like a reflection in a mirror. But there was more, a kind of vitality in the paint, an energy which made you feel that you had been let into a secret. It was as if the painter was showing you something that had always been there but you had never previously seen it.

She said, ‘How long will it take you to finish this?’

‘I need one more sitting, a couple of hours may be.’

‘All right. I’ll come back tomorrow and I’ll bring the money with me.’

Niamh returned the following evening. This time it was she who was quiet. She sat for him in silence, only speaking when he asked her a question, which he did rarely.

When he had finished she stared at the canvass for several minutes, then she said, ‘It’s magnificent. You are a great painter. I’ve had portraits done before, and I may have them done again, but never like this. This painting will stay with me always, for the rest of my life.’

‘Thank you,’ he said, and then he fell silent.

‘I’ll take it with me now,’ said Niamh, ‘I know the paint will take a few days to dry, but I have someone with me to help take it away.’

He looked at her in a questioning, puzzled way.

‘Miles is here to help, he’s my boyfriend and he’s downstairs now. Miles is more cynical than me, he doesn’t always take things at face value; I suppose that’s one of the reasons that I need him, he stops me from following my heart into places I shouldn’t go to. Miles did a lot of checking and found out that you’re not my cousin. The real Aaron lives in Spain, Miles actually found him and called him earlier today, so we’re quite sure. You are a great painter though, perhaps a better painter than you realise yourself. I’ve brought you some money.’ She reached into her bag and brought out an envelope. ‘Ten thousand dollars, which is how much I’m going to pay you for the painting. Please make sure you leave the Westminster by tomorrow, and please don’t contact any member of my family again.’

If you would like to know more about Niamh Ryan you should read the full length novel Cruel Sister

http://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B00BNHPSG0