When Did We Get So Griefy?

BBC2 is currently part way through a documentary series called Keeping Britain Alive: A Day In The NHS. I haven't seen it but I have seen the trailers. The whole series was filmed in one day with 100 camera crews trying to capture the enormity of what happens in the National Health Service which is, apparently, this nation's biggest institution. In the trails for it, we are told that on any given day 1,300 of us die and 2,000 of us are born.

One thousand, three hundred of us. Daily. That's a lot of dying. For each and every one of those 1,300 deaths someone, somewhere mourns. Or at least I (sort of) hope they do... because to contemplate someone passing away leaving nobody to feel their loss seems bleaker and sadder still.

When someone you love passes it goes without saying that the sadness is deep. And it is deeply individual too. But every day we hear about the deaths of strangers and in comparison it barely registers. Of course it can stir some emotions - but none of us is able to pretend that it compares to the death of a loved one. At times we all read news stories that involve the death of a stranger, tut, feel perhaps a blip of sadness and then turn the page. It doesn't make us unfeeling animals, it makes us human. Grief is not the normal response to the death of a stranger... if it were, we would all be in a permanent state of grief and then none of us would get on with living for all the death that surrounds us. Of course we empathise with those who have lost loved ones, but that's not the same thing. We sometimes raise a glass to those whose lives touched ours from afar. And we contemplate our own mortality when it turns out the pop stars we sang along to in our youth don't actually live forever. But we also turn the page and get on with things.

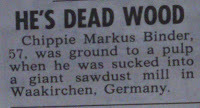

This is a recent story from one of our red top tabloids:

It's not just the opening paragraph... it's the whole story, as reported, in its entirety. What a way to talk about a man's death! What a way to talk about a man's life. Fifty seven years and he gets one cor-blimey-would-you-believe-it! sentence.

What are we supposed to think when we read this story? What, if anything, are we being invited to feel? Sadness? I don't think that's the writer's intention. Amazement? Maybe.

How many people do you think read this? How many of them do you think have given Herr Binder a second thought since?

But it seems that when a celebrity passes, the rules are different. Because we know who they are we feel they are not strangers. But they are. Aren't they? We seem to have become, well, something of a griefy bunch.

Not long after Whitney Houston died I was taken to task by a stranger on Twitter for the insensitive way in which I'd responded to that sad news. Which was odd to me because I hadn't mentioned her passing at all. Not on twitter. Nor anywhere else for that matter. When I read the news, I registered my surprise to a friend and then - rightly, I think - regarded it as nothing-to-do-with-me.

And that was what had upset him. It was, he thought, disrespectful of me to not tweet an RIP message. Things have come to a pretty pass when the absence of mourning is considered an insult.

I don't know when we became so griefy as a nation. (Nor do I know if it is confined to these shores). Is it trite to call it a symptom of our Post-Diana world? It probably is. But that was certainly a time when the failure-to-mourn was seen by some to be an active sign of rebellion rather than, y'know, normal. I think it's connected.

But I think things have been magnified by the growth of the internet in general and of Twitter in particular. In a world where everyone can express every nano-thought in an instant, some people do just that. Because they can. Because it's there. It might be a good reason for climbing Mount Everest but it's a lousy one for tweeting what you had for breakfast.

When Stephen Gately died there was a Twitter campaign to get one of Boyzone's singles to number one "in his honour". I suspect that was in part fuelled by the anger stirred up by Jan Moir's Daily Mail opinion piece on his passing. As insensitive a piece of writing as I can recall. The article had angered me but I couldn't begin to understand the campaign. I was asked to retweet a "let's all buy his single" message and when I didn't do so, one person told me that my failure to get on board meant I was insulting his memory. I wasn't. I just didn't want to own a Boyzone single. That's not an insult to Stephen Gately. More to the point, it's not an insult to his memory.

I am unable to feel true, deep sadness about someone's death unless it is someone I know. Does that make me a bad man? I don't think so. When musicians I admire die, they live on in my record collection. I do not lose them. Their children lose a parent, their parents lose a child and their partners lose a lover and my feelings are only for those people. It seems selfish to me to think otherwise. But if you feel differently - if your connection to a performer feels stronger than that and you feel a deeper sadness, then that's fine by me. But please don't make the assumption that we must all feel the same emotion to the same degree and that anyone not doing so is being rude. That's not fair.

For what it's worth, I can't celebrate a death either. And it probably hasn't escaped your attention that this blog is appearing at a time when many appear to be doing just that. I'm as non-plussed by that as I am by those who want us all to grieve. It's nothing to do with me. But then, in truth, it's nothing to do with most of us and that hasn't stopped people weighing in on both sides.

I suspect it would have happened to some degree no matter what. But I wonder if it would have had the same focus? Some of it feels more reactive than that. Some of it feels like people cocking a snook at those who assumed the whole nation would be plunged into mourning. A sort of, "well, if you're going to demand our reverence, we'll show you just how irreverent we can be", stance. And the louder one side screams that we should all be sad, the louder the others will scream that they're happy. And vice versa.

The magnitude of one's achievements does not, for me, magnify the sadness of one's death. What it magnifies is the font used to report it and the number of column inches given over to it. Most of us will get nothing. Markus Binder got one not particularly reverent sentence. Others get pages 1-14 of every newspaper and "souvenir" pull out sections to boot. That doesn't make their passing sadder. Not really. Not for those of us who didn't know them. Not for me, anyway. It just makes it louder. Bigger. More. And if you amplify the response - you amplify all of it.

One thousand, three hundred of us. Daily. That's a lot of dying. For each and every one of those 1,300 deaths someone, somewhere mourns. Or at least I (sort of) hope they do... because to contemplate someone passing away leaving nobody to feel their loss seems bleaker and sadder still.

When someone you love passes it goes without saying that the sadness is deep. And it is deeply individual too. But every day we hear about the deaths of strangers and in comparison it barely registers. Of course it can stir some emotions - but none of us is able to pretend that it compares to the death of a loved one. At times we all read news stories that involve the death of a stranger, tut, feel perhaps a blip of sadness and then turn the page. It doesn't make us unfeeling animals, it makes us human. Grief is not the normal response to the death of a stranger... if it were, we would all be in a permanent state of grief and then none of us would get on with living for all the death that surrounds us. Of course we empathise with those who have lost loved ones, but that's not the same thing. We sometimes raise a glass to those whose lives touched ours from afar. And we contemplate our own mortality when it turns out the pop stars we sang along to in our youth don't actually live forever. But we also turn the page and get on with things.

This is a recent story from one of our red top tabloids:

It's not just the opening paragraph... it's the whole story, as reported, in its entirety. What a way to talk about a man's death! What a way to talk about a man's life. Fifty seven years and he gets one cor-blimey-would-you-believe-it! sentence.

What are we supposed to think when we read this story? What, if anything, are we being invited to feel? Sadness? I don't think that's the writer's intention. Amazement? Maybe.

How many people do you think read this? How many of them do you think have given Herr Binder a second thought since?

But it seems that when a celebrity passes, the rules are different. Because we know who they are we feel they are not strangers. But they are. Aren't they? We seem to have become, well, something of a griefy bunch.

Not long after Whitney Houston died I was taken to task by a stranger on Twitter for the insensitive way in which I'd responded to that sad news. Which was odd to me because I hadn't mentioned her passing at all. Not on twitter. Nor anywhere else for that matter. When I read the news, I registered my surprise to a friend and then - rightly, I think - regarded it as nothing-to-do-with-me.

And that was what had upset him. It was, he thought, disrespectful of me to not tweet an RIP message. Things have come to a pretty pass when the absence of mourning is considered an insult.

I don't know when we became so griefy as a nation. (Nor do I know if it is confined to these shores). Is it trite to call it a symptom of our Post-Diana world? It probably is. But that was certainly a time when the failure-to-mourn was seen by some to be an active sign of rebellion rather than, y'know, normal. I think it's connected.

But I think things have been magnified by the growth of the internet in general and of Twitter in particular. In a world where everyone can express every nano-thought in an instant, some people do just that. Because they can. Because it's there. It might be a good reason for climbing Mount Everest but it's a lousy one for tweeting what you had for breakfast.

When Stephen Gately died there was a Twitter campaign to get one of Boyzone's singles to number one "in his honour". I suspect that was in part fuelled by the anger stirred up by Jan Moir's Daily Mail opinion piece on his passing. As insensitive a piece of writing as I can recall. The article had angered me but I couldn't begin to understand the campaign. I was asked to retweet a "let's all buy his single" message and when I didn't do so, one person told me that my failure to get on board meant I was insulting his memory. I wasn't. I just didn't want to own a Boyzone single. That's not an insult to Stephen Gately. More to the point, it's not an insult to his memory.

I am unable to feel true, deep sadness about someone's death unless it is someone I know. Does that make me a bad man? I don't think so. When musicians I admire die, they live on in my record collection. I do not lose them. Their children lose a parent, their parents lose a child and their partners lose a lover and my feelings are only for those people. It seems selfish to me to think otherwise. But if you feel differently - if your connection to a performer feels stronger than that and you feel a deeper sadness, then that's fine by me. But please don't make the assumption that we must all feel the same emotion to the same degree and that anyone not doing so is being rude. That's not fair.

For what it's worth, I can't celebrate a death either. And it probably hasn't escaped your attention that this blog is appearing at a time when many appear to be doing just that. I'm as non-plussed by that as I am by those who want us all to grieve. It's nothing to do with me. But then, in truth, it's nothing to do with most of us and that hasn't stopped people weighing in on both sides.

I suspect it would have happened to some degree no matter what. But I wonder if it would have had the same focus? Some of it feels more reactive than that. Some of it feels like people cocking a snook at those who assumed the whole nation would be plunged into mourning. A sort of, "well, if you're going to demand our reverence, we'll show you just how irreverent we can be", stance. And the louder one side screams that we should all be sad, the louder the others will scream that they're happy. And vice versa.

The magnitude of one's achievements does not, for me, magnify the sadness of one's death. What it magnifies is the font used to report it and the number of column inches given over to it. Most of us will get nothing. Markus Binder got one not particularly reverent sentence. Others get pages 1-14 of every newspaper and "souvenir" pull out sections to boot. That doesn't make their passing sadder. Not really. Not for those of us who didn't know them. Not for me, anyway. It just makes it louder. Bigger. More. And if you amplify the response - you amplify all of it.

Published on April 12, 2013 13:13

No comments have been added yet.

Dave Gorman's Blog

- Dave Gorman's profile

- 202 followers

Dave Gorman isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.