On masculinity

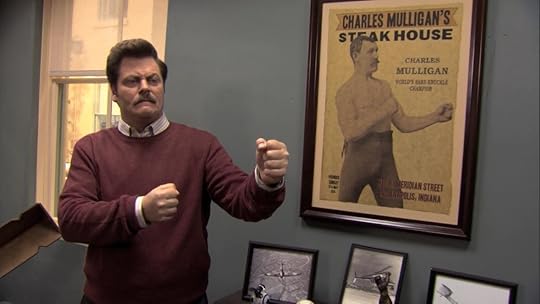

Probably one of the most feverishly adored characters on television right now – among a certain demographic of viewers, including myself – is Ron Fucking Swanson.

Probably one of the most feverishly adored characters on television right now – among a certain demographic of viewers, including myself – is Ron Fucking Swanson.

Why? Because Ron Swanson is old school masculinity to the point of deconstruction. He’s uber-competent. He’s indifferent, and supremely dismissive. He’s self-reliant, and confident. He’s contemptuous of anything emotional or modern. He doesn’t need anything, and he’s definitely not going to ask you for anything. He’s a walking, talking anachronism, an early 20th Century Man (or even 19th Century) living in the 21st Century – without, you know, the racism, sexism, and so on.

A lot of this character’s appeal comes from the brilliant work of Nick Offerman, the actor who plays him. Offerman underplays Swanson to an unbelievable degree, usually donning a dead-eyes scowl and murmuring his lines with a Midwestern nasal growl. And a lot of Swanson is based on Offerman, a Midwesterner, carpenter, and respectful manly man.

A lot of the love for Swanson dovetails with a broader trend for the ornaments of old-school American masculinity: beards, mustaches, pipes, pomade-slick hair, and a lot of dark wood, 19th century interior designs are currently the hippest of hip. This has led some to speculate on the state of masculinity in America: do the progressive, hip men of today adore the men of bygone eras because they know their own testosterone isn’t up to snuff?

To which I respond: eh.

The historical aspect

As Ron Swanson is, in a lot of ways, an amalgam of masculine archetypes from anywhere from the 1890’s to the 1950’s, it’s worth examining those actual historical eras, and what was happening. This nostalgic perception of masculinity didn’t come from nowhere, after all.

In a few broad strokes, from the 30′s to the 60′s, you had around two whole generations of men who had been in overseas combat and had gone to school on the GI Bill. This was probably the largest civic mobilization of a demographic in American history: not only training generations of men to be highly resourceful, self-reliant servants (while also learning to operate within a system – for what bigger system is there than the American military?), but also actually, genuinely teaching them, sending them to school to learn things they never got the chance to before.

And that’s probably a huge factor: the men Ron Swanson seems to reference were likely the very first people in their family’s history to achieve this level of education and success. These people were given incredible opportunities (under incredibly hardships, of course) at a time when America was firing on all cylinders. I sincerely doubt if any large demographic is or could be placed in such a sweet position today.

In addition, it’s worth noting that these opportunities in those eras were only offered to a select few. Women did not get any of those opportunities, so that’s half the population right there that’s not competing. Minority males may have gotten some degree of these opportunities, but I’m willing to bet that whatever they got was a much-reduced package in comparison to what white males received. So you had one specific demographic that essentially got handed the keys to what was, at the time, a brand-new, incredibly nice car, and everyone else got to watch them drive it away.

But things go beyond the historical perspective. Not only do we not have the opportunities that created men who were, to an extent, like Ron Swanson – we also don’t have much need for one of their greatest virtues.

We don’t do that anymore

The appeal of Ron Swanson (and the fundamental appeal of general masculinity, I think) is the concept of resourcefulness. Ron Swanson doesn’t buy a house: he goes out in the woods, chops down 30 trees, and builds one. He doesn’t get his car serviced: he fixes it himself, and if he needs a part he smelts one in his own goddamn smithy.

Not only do I think that, on the whole, that’s not what we’re training or preparing coming generations to be, but I also think that way of life is more or less defunct. We’ve developed our economy and our culture in a manner that it’s easier to buy a new shirt than it is to fix your old one. If your kitchen appliance breaks down, we are not trained to take it apart and fix it – we just go to Target and get a new one. We’re slowly entering a stage of post-scarcity, where we have an abundance of goods, and a better use of your time is not to fix or repair the cheap thing you have, but to get a new one – something the people in the 30′s, 40′s, and 50′s probably thought was unimaginable.

This also extends to cars and computers. Apple specifically makes it so you can’t take Powerbooks apart and noodle with them: they want you coming back to the store. Cars these days are more computers than machinery, and I dread the idea of trying to do work on my Prius. (Cue my wife laughing immensely.)

This isn’t to say that this is a good or a bad thing – it is what it is. This is the world that we’ve chosen. We’ve opted to maximize individual buying power over individual resourcefulness. Ideally, this means we spend less time on the day-to-day minutiae of living – mending clothes, fixing cars, fixing your house – and more time on greater abstracts previous generations didn’t have the time for. (Reality television, pornography, etc.)

We’ve made a trade, in other words, but I think we’re discovering that we valued the pride derived from that resourcefulness more than we thought.

However, it is worth noting that this new economy, driven by extreme quantity, is possibly a creation of another 20th Century masculine archetype.

So what’s a man to do these days?

I think it’s time for a reconceptualization of what we think it is to be a man.

I was thinking of my own ideas about masculinity, which change the older I get. I’m not a kid anymore. I have a wife, a son, and I essentially work two to three jobs. I don’t spend three hours a day at the gym like I used to. I don’t drink beer all the time and I don’t rotate through a series of women. And I don’t especially know a huge amount about home repair or fixing up my car. (Landscaping is another matter, though.)

So what I do I, personally, think of as masculine? Well, I was casting around for an icon manliness that would work in the 21st Century – or indeed any century – and what I came upon was a little less Ron Swanson, and a little more…

Aah, yes. That’s a lot more like it.

The more I think about it, my ideal perception of masculinity has a lot less to do with the material world – what you can do with your hands and your body – and a lot more to do with the moral, abstract one.

So I made a list of qualities I think of as masculine, ones that I feel have a lot more applicability these days.

1. A consciousness of others

A real man puts others ahead of himself. He thinks about what those around him need, about what his community needs, about the larger picture beyond just himself, what he wants, and his own goals. He thinks not only about other people, but about what other people think and how they think it, and he’s willing to change his viewpoint and be persuaded based on these considerations.

2. A devotion to supporting and providing for the family

Here’s what I define as a family: a close-knit group of people that learns from you, while also teaching you plenty of things. Blood or familial relation is not a necessity, at all. And I do think, increasingly, that a willingness to share your life with others is a much better good than complete and utter independence and detachment. And I personally identify a willingness to work, support, teach, and learn from the people you’ve shared your life with as a very masculine quality.

3. A willingness to reconsider and compromise

I think a real man prioritizes, figures out which good things are most important, and is willing to put lesser good things on the line in order to have the best impact for the most amount of people. The ability to be reasoned with and persuaded seems to be a rare thing these days; in fact, the very opposite appears to be considered a masculine quality now: the most stridently belligerent and bull-headed people are usually considered manly men.

And that’s really it. These are the three things I identify as the Atticus Finch Brand of Masculinity.

But once I thought about this, I realized something.

What I’m laying out here isn’t masculinity: these are basic moral tenets. If you reread the three qualities I laid out here, and replace “a real man” with “a good person” and “masculine” with “moral,” then this whole thing still makes perfect sense.

Anyone can have any of these qualities and still be considered whatever the hell you want to be considered as – they’re functionally genderless.

Being a good person is manly. Being a good person is feminine. Being a basically decent person should be, in other words, the centerpiece of any sort of ideal human being, regardless of gender, creed, or nationality – and doing so does not detract from that ideal, only add to it.