Rust Never Sleeps

On the day that Margaret Thatcher left office–on the day she was driven from office, bundled into a car and carried away from Downing Street, sobbing–I was living in Bournemouth, working off my student debt. I bumped into a work colleague, who told me the news. We found a pub, and cheerfully toasted the fall of an enemy.

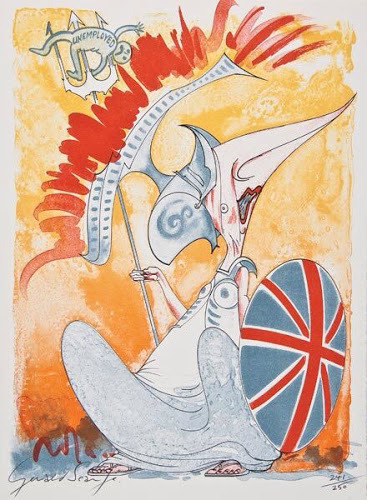

Now, many years later, as I find my newsfeeds swelling with the news that a rogue circuit in her head has finally popped and switched her off for good, I wonder whether celebration is appropriate. She was, after all, a dim shade of the warrior queen that bestrode the affairs of the nation, wild-eyed, her bared teeth set against her many foes. A sick old woman, her past victories no defence against the simple passage of time. For a generation born into Blair's Britain, she means nothing. That's something of a victory in itself.

If only she could be forgotten. The papers and TV have her face on permanent rotation, grinning like a basilisk from every screen and front page. There is a wild scramble to eulogise, to praise her many accomplishments, to gloss over her failings in the misguided notion that it isn't done to speak ill of the dead.

I”m afraid I have no such compuction, and I'm not in the mood to be polite.

When I think of Thatcher, all I can think of are the bad things. The destruction of working communties, the dismantling of our manufacturing base, the sell-off of our rail network, our utilities. Ultimately, the commodification of our very souls. Under Thatcher, we became a meaner, crueller, less unified nation. The collapse of the safeguards which were put in place as we stepped away from the horrors of World War 2 and realised that actually, it's not such a bad idea to look after each other, all of that started on her watch. I'm not alone in thinking that she held on just long enough to see the dismantling of the NHS and the welfare state, just enough to be able to gloat at the culmination of all her dark ambitions in her shadow-barred suite at The Ritz.

There is a school of thought that we should seperate the woman from her deeds, that we should remember her grieving family and show a little respect. Fair enough. Let's show her the same respect she showed to the miners of Wales and the Midlands, to the people she stigmatised under Section 28, to everyone who showed weakness, or dared to ask for a little help. She hated the working class, seeing in them the roots of a past she wanted to erase. She had no time for women, the poor, the dispossessed, the vulnerable. You can't seperate the woman from her actions. Her actions defined her.

Do I sound angry? Too bloody right. Every time I look at a picture of the woman, I feel a little sick. I couldn't go near the recent revisionist biopic of her life. It was like a horror movie to me. Even the trailer gave me the shudders. I lived with her cruel, divisive policies through my teenage years, and her poisonous legacy lives on today like a toxic fog hanging over us. She spawned Blair and the ConDemNation. Her creatures stain our lives to this day, her economic strategies of benefit only to those she sought to emulate. Her presence has been a chip of cold black glass in my eye for decades, and I mark its removal with a single twinge of regret; that it should ever have been there in the first place.

Do I hate? Yes, I hate. But in the face of evil, hate is often the only appropriate response. Thatcher was a supporter of apartheid, dismissing Mandela as a terrorist. She was a friend to the mass-murdering Chilean dictator Pinochet. She stood against everything that a reasonable society, aware of the responsibility to its population, should embrace. Indeed, her repudiation of the very idea of society, embracing instead a power-crazed free-for-all that tramples our most needy and vulnerable underfoot tells you everything you should know about the woman. She took charge of a sickened country and gave it medicine that was closer to poison than potion. Putting this woman in charge of Britain was like putting your hand in a threshing machine when you needed a manicure.

So, will I celebrate? In my way, yes. There will be no bunting, no popping of corks. But I will tilt a glass, feeling in my heart and guts that little bit lighter, as if a twenty-year-old hangover has lifted. Her children still stalk our land, despoiling as they go. But they mourn tonight, and that brings me strength. These are dark times, but the passing of an enemy can always lift your spirits.

If only they'd play this at St. Paul's when they put her in the ground.