To fix PME, first we need to fix a national culture that doesn't value critical thinking

By Victor Glover

Best Defense guest columnist

The professional military education

(PME) system may need fixing, but in the service we don't value graduate

education and that needs to be fixed first.

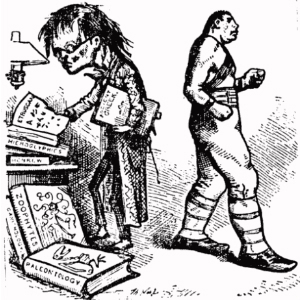

The military is a microcosm of

society and we suffer from the same anti-intellectualism (to borrow from Richard Hofstadter) that plagues

modern society. The military does not

have a critical thinking problem -- the whole country does. While I agree that we need to address the

range of problems with critical thinking (specifically analysis and

communication) I do not agree that the problem is undergraduate education and I take even

greater exception to the notion that technical education is a part of the

problem.

This problem does not begin in the

field-grade military, college, or even high school. We've had a critical down-turn in

junior-high/middle school compared to other developed

nations.

I specifically follow mathematics and science trends, however U.S.

education generally trends the same. If

you want to attack the worthwhile issue of accession quality, you are biting

off the mother lode. The data suggest

that we have to go back to around grade 5 to reach a steady-state

solution. I do work at this task, not

for the military's sake, but for the country's.

However, this is not something we can directly address from inside the

leaning military machine. So what then,

are we studying the wrong things?

History, politics, anthropology,

geography, and diplomacy are indeed pertinent disciplines for the officer of

today. Breadth of education, to include

scientific and technical education, is important for the officer of the

future. The real problems in life don't

come in boxes labeled "physics" or "sociology;" they demand the efforts of the

broadly and deeply educated and trained.

I will borrow from Consilience: the Unity of

Knowledge by the polymathic Edward O. Wilson. I will not try and summarize the wonderfully

complex tome, but please allow a long quotation:

Every

college student should be able to answer the following question: What is the

relation between science and the humanities, and how is it important for human

welfare? Every public intellectual and political leader should be able to

answer that question as well. Already half the legislation coming before the

United States Congress contains important scientific and technological

components. Most of the issues that vex humanity daily -- ethnic conflict, arms

escalation, overpopulation, abortion, environment, endemic poverty, to cite

several most persistently before us -- cannot be solved without integrating

knowledge from the natural sciences with that of the social sciences and

humanities. Only fluency across the boundaries will provide a clear view of the

world as it really is, not as seen through the lens of ideologies and religious

dogmas or commanded by myopic response to immediate need.

Specifically relating to the Treaty

(or Peace) of Westphalia, the impact of this series of treaties on the

relations of sovereign nations is indelible and important for the public

servant. Likewise are the technical and

contractual details of the multibillion (tax-payer) dollar F-35 Lighting II

aircraft program, their impact on the perceived success of the effort, and the

larger logistical and tactical impact of a single-point strike-fighter solution

on our common defense. PME is not just

about history. It is all things

operational and strategic to equip the field grade and above.

We in the military can address and

affect this strategic and operational deficit and the larger PME system. First, we have to understand the problem by

discussing the nature of the issue (as we are).

Then we can manipulate our recruitment, retention, and advancement

systems more effectively.

One of the reasons we do not have the

critical or strategic thinking en masse is that it is not always required. When it is required, we are trying to hone it

from professionals grown in an active warfighting organization, not always

conducive to critical and strategic development. We also live in a "do" oriented country and

are therefore in a "do" oriented military.

What we have to figure out is how to do while finding time to dialogue,

debate, philosophize, analyze, study, think, and sit still. Hopefully the end of this era of war will

encourage us to consider this.

The core of this issue however, is

not education or the availability thereof.

The large animals in the room are personnel management and

advancement. To inculcate critical thinking

across the department will require adjustments to our evaluation and promotion

systems. We in the warfighting

profession do not make up a monolithic bureaucracy. There are many facets to military service,

but we promote as if everyone is striving for the same goal.

We do not highlight the junior

personnel content with middle management as their highest aspiration while

mastering that realm. We also do not

reward the disciplined specialist in the operational force as we all have to be

generalists. In contrast to my earlier

statement about the broadly educated and trained, we focus too much on the

broadly trained and experienced and not enough on the broadly and deeply

educated. Somewhere there is balance we

are failing to strike.

In the Navy F/A-18 community we refer

to our training as being a jack-of-all-trades and master of none. I do not believe the promotion system is

wrong or improper for our mission, just that it is too rigid. Yes we have to cull the field, yet all

enlisted personnel do not want to be the senior enlisted advisor to the chief,

nor all officers the chief. Integrating

career flexibility and educational priority into our personnel system would

have a profound impact and I believe we are trying. If we change the system to value critical

analysis and communication abilities, where then do we attain these?

We are fed from and posses

institutions that can educate broadly and deeply, cultivating critical

thinkers. In my experience, Cal Poly,

the Naval Postgraduate School, and the Air Command and Staff College are among

these institutions possessing great educators.

Professors like Dan Walsh, Jim LoCascio, Gary Langford, Mark Rhoades,

and Jonathan Zartman understand the mission, the pupil, and the material, and

mush them together until they get the learning outcome they want. Put the Peace of Westphalia where it is not,

in the context of the learner, and you will undoubtedly root it in the minds of

your students. A facet of the solution

lies in the hands, heads, and hearts of the academe. Once the services reward rigorous graduate

education, we will also see the professorship, military and civilian, evolve

for the better. We will also see the

opportunities to attend the nations elite institutions grow and expand, also

for the better. In today's fiscally

constraining environment, civilian graduate institutions may serve as a bulwark

in maintaining a professional and educated officer corps.

Another facet of the solution lies

with the individual service member. I am

a carrier-based aviator and test pilot serving as a fellow in the legislative

branch of government. After this stint

in the staff world I hope to return to the operational flying world. I cannot rightly blame the Navy for the

difficulty in training and educating me to think and communicate effectively. What are they to train me for next? At each juncture in my career I didn't know where

I would be next until I got the call to pick up and leave. However, I have always been given what was

required to do my job whether landing on a carrier, evaluating weapon systems,

or supporting the legislative process.

An important part of a servicemember's

critical development is his or her personal and professional duty. We are most useful when equipped to deal with

a range of problems even before we are required to. I want to give my best in service, so I ought

to grasp the opportunities to get better with both hands. My career has given me a context to

appreciate subjects that I did not appreciate when I was a full-time student.

Context has helped me grow concern for the way these subjects affect my life

and service. I would love to go back and

be an undergraduate again but I cannot, so I take every opportunity to learn

while I can. Does our professional

military education system need righting?

Not as much as our understanding of the importance of education within

the military.

Lieutenant Commander Victor Glover (@VicGlover ) is

a graduate of Cal Poly, Officer Candidate School (with distinction), Air

Command and Staff College (with distinction), Air Force Test Pilot School, and

the Naval Postgraduate School. He recently completed a tour as a department

head in a strike-fighter squadron and is currently a legislative fellow in the

United States Senate. The views expressed are his own.

Thomas E. Ricks's Blog

- Thomas E. Ricks's profile

- 436 followers