Being Seen

I read a poem this morning, the first of the poems that will be published on Tor.com as part of Poetry Month. It’s by Neil Gaiman, and it’s called “House.” It starts like this:

“Sometimes I think it’s like I live in a big giant head on a hilltop

made of papier mache, a big giant head of my own head.”

The poem describes how the man lives in a house shaped like his own giant head, cleaning the windows (which are the eyes), mowing the grass around it. And people drive past, waving not to him, but to the giant head, because “they think the house is me.” It isn’t, of course.

What it is, is a metaphor. I suppose a giant house shaped like a head would have to be!

The most important lines of the poem, to me anyway, are these:

“I’ll be sleeping there, or polishing the eyes, or weeding the lawn,

but no-one will see me, no-one would look.”

There’s a sense in which this is a poem about being someone like Neil Gaiman, someone so famous that he is no longer seen as a person. People no longer see him. They see the giant Neil Gaiman head. But it’s also a metaphor for how we experience other people in general: we so often don’t see them, and they so often don’t feel seen. Instead, we see who we think they are, the giant heads of themselves. The houses they inhabit, not the selves that are the inhabitants.

Strangely enough, some of the most authentic people I’ve met have been people who are famous. It’s as though they insist on authenticity — they insist on being themselves, specifically because they feel as though they are being made artificial. They know that people don’t see them, and so whenever they can, they insist on being seen as they are, even if that image is not particularly flattering. They take actions or express opinions that may be controversial, that may cause debate, but reflect what they think and feel. They want, so much, to be seen not as constructs, but as people.

It’s uncomfortable, not being seen as a person.

But we all get that to a certain extent: the giant heads we live in are constructed partially by us, but also partially by others, by who they think we are. And if we are writers or artists, there’s an assumption that we are our writing, our art.

There’s something I’ve learned about writing these posts, which is that when they become hard to write, when the sentences feel like snakes twisting around in my hands, it’s because the subject it too personal. It hits too close to the giant head that is my home. And this subject is personal, I think. Because we all get this, and I get it too: the sense of living in an artificial construct that is perceived as my self, that is addressed instead of me. The value of friends is that they see you, the real you: they automatically look through the windows and know you’re in there. One of the saddest thing, I think, is meeting someone you would like to be a friend who doesn’t do that, who can’t seem to see the person in the construct.

There is a particular pain in not being seen. In not being perceived as a person.

A friend of mine and I were talking about this last summer, sitting in my grandmother’s apartment in Budapest: two women who write fantasy, discussing how easy it seems for people to confuse the writer with the work, or even simply with an image online.

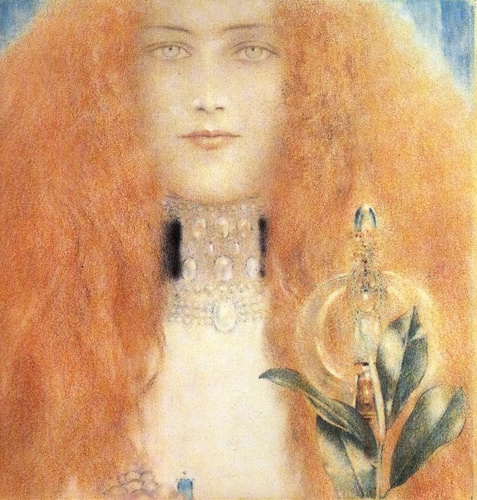

As my illustration for this post, I’ve chosen A Woman’s Head by Fernand Khnopff. She’s beautiful, isn’t she? Iconic, almost. But she must have been a real woman who modeled for the artist. I wonder who she was, and what she was like as a person . . .