Doing disruption right

In my previous post, I told a story about doing disruption the wrong way. I violated the principles that make disruptive thinking effective, with disastrous consequences. In this post I’d like to share one time when I really got it right.

In my previous post, I told a story about doing disruption the wrong way. I violated the principles that make disruptive thinking effective, with disastrous consequences. In this post I’d like to share one time when I really got it right.

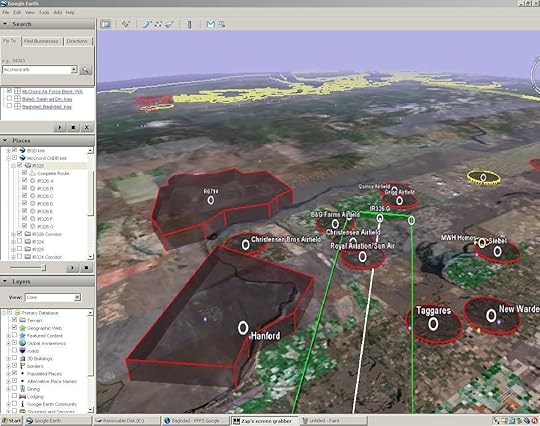

When I was a C-17 copilot, Google Earth was still relatively new and pilots in my squadron were trying to put it to work. It was a great tool for visualizing 3D terrain, especially for airdrop run-ins in Afghanistan’s mountainous terrain. Unfortunately, it wasn’t easy to use; there was no way to link it to the DOD’s mission planning software (PFPS/FalconView), so pilots had to manually enter coordinates for each point. I thought there had to be a better way.

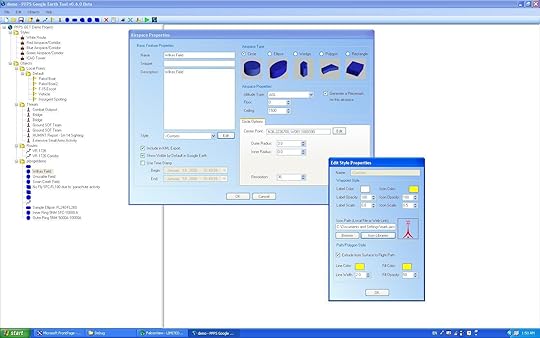

I spent the next year developing a powerful software program that would convert PFPS data into a format readable by Google Earth. By the time I was done, it could map routes, plot threats, and manage large collections of colorful 3D airspace. I was extremely proud of the finished product, and released it through a slick website that included a PowerPoint briefing and capabilities demonstration.

I spent the next year developing a powerful software program that would convert PFPS data into a format readable by Google Earth. By the time I was done, it could map routes, plot threats, and manage large collections of colorful 3D airspace. I was extremely proud of the finished product, and released it through a slick website that included a PowerPoint briefing and capabilities demonstration.

The PFPS Google Earth Tool met a legitimate need, and spread quickly among the crew force. Still, there were obstacles. Google Earth wasn’t authorized on Air Force computers. Most of us got around this by running GE from thumb drives, back when that was allowed (sort of), but it wasn’t an optimum solution. It also wasn’t certified; I couldn’t guarantee the output was 100% accurate. This was a rough tool to assist pilots, but nothing more.

As the tool caught on, I started getting phone calls. A C-130 pilot had used GE to create orientation videos of the drop zone run-ins used by his unit. He sent me a disk. A Pentagon staff officer in charge of procuring geospatial tools wanted to use my work to build his case for procuring Google Earth. A network administrator offered to migrate the tool to SIPRNET, so it could be used for classified missions. The most important call came from a Major at a USAFA think tank known as the Institute for Information Technology Applications. They were developing a suite of mission planning tools called Warfighter’s Edge (WEdge) and were intrigued by my work. They paid for a TDY out ot USAFA, where I hung out with their coders and briefed the retired 4-star who ran the Institute.

Until this point, the software had been my baby. I’d developed it singlehandedly, and was excited to see it take hold around the Air Force. But I also knew that I was hitting the ceiling of my capabilities. The WEdge team offered resources I didn’t have access to: a budget, an entire team of engineers and programmers, access to higher Air Force leadership, and the ability to get software products certified for Air Force use. I made the painful decision to give them all my code, and transfer full responsibility for the product to their office. In the year’s since, WEdge has integrated my work into a tool called WEdge Viewer. It is now Air Force-sanctioned, certified for flight, and in use throughout the Air Force.

This was a success story, and it was a success because I obeyed the principles laid out in my essay. I found allies (or rather, they found me). We were able to persuade higher leaders in the Air Force, because we had an excellent product to “sell” and it was packaged well. We offered something positive and constructive, that could meet legitimate needs. My allies were able to work through difficult challenges, like flight certification and authorization for installation on government computers.

Most importantly (and most painfully) I was willing to share credit. I let others run with my idea, and they made it into something great. I’ll admit this hasn’t been easy. The tool is in use across the Air Force now, but even my own peers now don’t know that I designed the initial application. But hey, I changed something, and that’s pretty awesome. Change in a large institution is always a team sport.