Words? Who needs them? by Gill Robins

Welcome to guest blogger Gill Robins. Gill was a leading English teacher who now reviews for Books for Keeps, is a Senior Editor and a published author, too. The Whoosh Book, an interactive approach to teaching classic and contemporary text through drama, is due for publication in May 2013. Gill was awarded the UKLA John Downing Award for creative and innovative approaches to teaching English. Her thoughtful and insightful blog is at http://teacherturnedwriter.gillrobins.com/

I’ll start this blog with something of a confession, because, as they say, confession is good for the soul. I love reading picture books just as much as I love reading Kafka or Dickens. And therein lies the conflict.

Now I realise that if you’re reading this blog you’re already converts to my cause –in fact, you probably never needed converting. My cause, I hear you ask? Simply this: to persuade parents of the vital importance of picture books and image in the development of their children’s reading. Let me take you on a journey into my world...

Although I’m now a writer and editor, I spent most of my working life as a teacher, for the final ten years leading English in a school and training Primary school teachers to teach the subject rigorously and with passion. I mostly failed, I think, with the passion bit and here’s why. We live in a world where the written word is enshrined as an end goal, where word writers are put on pedestals and our education system is relentlessly geared to the mastery of words as some sort of Holy Grail. I tried to broaden the definition of ‘read’ and it met with deafening disapproval.

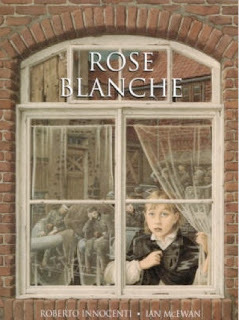

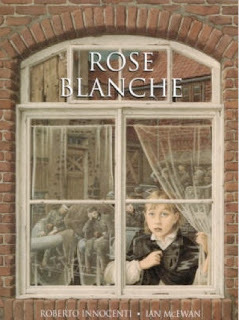

I mostly taught at the top end of Key Stage 2 (9-11 year olds), by which time the majority of pupils could, of course, read fluently. When I (naively as it turned out) introduced a complex picture book into the curriculum (Roberto Innocenti and Ian McEwan's Rose Blanche) several children refused to look at a picture book which was ‘just for babies’. Then the parents joined in the fray. How would their children get Level 5 SATs/A* GCSE English/a place at Oxbridge by reading baby books? What on earth was I thinking? Didn’t I realise how important it was to introduce them to the canon of classic literature as early as possible (preferably in utero) in order to gain advantage?

I define reading much more widely than just the written word and nothing in my experience has yet convinced me otherwise. Babies and toddlers can read gesture and body language fluently; it follows that they can also read image just as effectively. So although the traditional view is that pictures exist in books to entertain toddlers, introduce them to the concept of a book and then clue early readers into text, my view is that this is too limiting a definition of the role of image. I think it can be read as a medium in its own right and therefore is not something that we should train children out of as print starts to predominate.

Ok, so now you’ve kindly read my rant, here are just a few of the picture books that I have found enriching in the experience of the children I have taught. Let’s start with:

Rose Blanche. This tells the story of one little girl who stumbles across a concentration camp on the outskirts of her town during World War II. I provided this without any text as we went on a journey of discovery through the book. Here are some of the comments that children made and the questions they asked, discussed and wrote about:

‘Why have all the grown-ups turned their backs? Why do grown-ups do that?’

‘I can see her feelings in the reflection in the window – like mirrors.’

‘The way that picture bleeds right out to the edges of the page – it makes you realise how many Jews were killed. There was no end to it. It went on for ever.’

‘The buildings are huge and dark. They fill up most of the picture. It makes you realise how frightening the camps were. Like the buildings are big bullies.’

‘I’ve never realised before that a fence can be a barrier.’

As the war comes to an end, Rose stumbles through the forest in thick fog. On the opposing page, a frightened German soldier fires into the fog. In the final image, a flower which she had picked lies dead over a barbed wire fence. On a mound below the fence, new flowers blossom. These final images provoked really intense discussion. If I had ever needed persuading about the power of image in developing skills in inference and deduction, it would have been this experience that would have persuaded.

Some children decided that Rose had abandoned the flower, found her Mum and lived happily ever after. Some children read into the image that she had been shot by the soldier even though she was also German, the mound being her grave. All children discussed new life and its continuation even after the Holocaust. And only image can provide children with the opportunity to discuss intense, emotional issues from within their own understanding. Words have to spell it out too clearly to afford the opportunity for much interpretation. Could ten-year-olds have gained such an in-depth understanding of such a difficult issue from a print book?

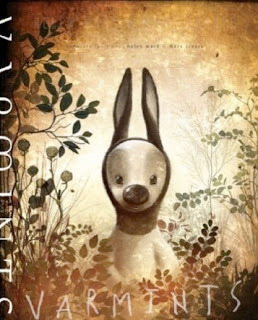

My next ‘favourite’ is Varmints, by Helen Ward and Marc Craste. This is a touching story about the need to make time and space in our modern world. It feels cinematic, with see-through pages that create a soft-focus effect to some of the images. I thought I’d let a nine-year-old comment on this one for you:

‘One page is completely black. Probably the people’s minds were turned off. It doesn’t need words because I can make up my own story. The book goes from light when the Varmint is happy to dark in the middle then light suddenly comes back because the Varmints world has come back. You can read the book backwards because it goes from light to dark to light whichever way you read it. You feel like you’re in a film.’

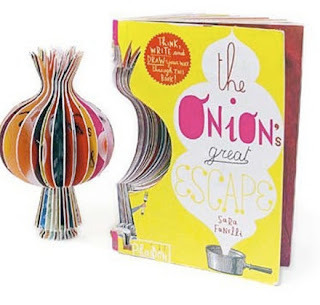

And finally, Sara Fanelli's The Onion’s Great Escape – an amazingly powerful book which engages the reader in philosophical thinking at really deep levels. In case you’ve never read Sara’s books, you tend to form relationships with them rather than read them. This book is part poetry, part narrative and part philosophy. You also create your own new book as you release an onion from confinement. If you want to encourage children to challenge conformity and tradition, this is the book to share with them.

Sara’s work is typified by collage, a medium which she loves and which she feels that children engage with quite naturally. I spent hours when I first read this book gazing at the different collage materials, going off on thought tracks of my own. Then there are the scribbles which you can imagine to be anything... a very personal, visual experience. I haven’t read this book with anyone yet because releasing the onion will be a very special moment, for which I am waiting for a very special child.

So, words, who needs ‘em?

Well, we all do, of course. I’m not arguing for the abandonment of word books, merely an expansion of parental vision to allow for the enrichment of children’s reading experiences. But with the relentless, narrow view of reading and its mastery, which is the Emperor’s current new clothes, I don’t see it coming any time soon.

I’ll start this blog with something of a confession, because, as they say, confession is good for the soul. I love reading picture books just as much as I love reading Kafka or Dickens. And therein lies the conflict.

Now I realise that if you’re reading this blog you’re already converts to my cause –in fact, you probably never needed converting. My cause, I hear you ask? Simply this: to persuade parents of the vital importance of picture books and image in the development of their children’s reading. Let me take you on a journey into my world...

Although I’m now a writer and editor, I spent most of my working life as a teacher, for the final ten years leading English in a school and training Primary school teachers to teach the subject rigorously and with passion. I mostly failed, I think, with the passion bit and here’s why. We live in a world where the written word is enshrined as an end goal, where word writers are put on pedestals and our education system is relentlessly geared to the mastery of words as some sort of Holy Grail. I tried to broaden the definition of ‘read’ and it met with deafening disapproval.

I mostly taught at the top end of Key Stage 2 (9-11 year olds), by which time the majority of pupils could, of course, read fluently. When I (naively as it turned out) introduced a complex picture book into the curriculum (Roberto Innocenti and Ian McEwan's Rose Blanche) several children refused to look at a picture book which was ‘just for babies’. Then the parents joined in the fray. How would their children get Level 5 SATs/A* GCSE English/a place at Oxbridge by reading baby books? What on earth was I thinking? Didn’t I realise how important it was to introduce them to the canon of classic literature as early as possible (preferably in utero) in order to gain advantage?

I define reading much more widely than just the written word and nothing in my experience has yet convinced me otherwise. Babies and toddlers can read gesture and body language fluently; it follows that they can also read image just as effectively. So although the traditional view is that pictures exist in books to entertain toddlers, introduce them to the concept of a book and then clue early readers into text, my view is that this is too limiting a definition of the role of image. I think it can be read as a medium in its own right and therefore is not something that we should train children out of as print starts to predominate.

Ok, so now you’ve kindly read my rant, here are just a few of the picture books that I have found enriching in the experience of the children I have taught. Let’s start with:

Rose Blanche. This tells the story of one little girl who stumbles across a concentration camp on the outskirts of her town during World War II. I provided this without any text as we went on a journey of discovery through the book. Here are some of the comments that children made and the questions they asked, discussed and wrote about:

‘Why have all the grown-ups turned their backs? Why do grown-ups do that?’

‘I can see her feelings in the reflection in the window – like mirrors.’

‘The way that picture bleeds right out to the edges of the page – it makes you realise how many Jews were killed. There was no end to it. It went on for ever.’

‘The buildings are huge and dark. They fill up most of the picture. It makes you realise how frightening the camps were. Like the buildings are big bullies.’

‘I’ve never realised before that a fence can be a barrier.’

As the war comes to an end, Rose stumbles through the forest in thick fog. On the opposing page, a frightened German soldier fires into the fog. In the final image, a flower which she had picked lies dead over a barbed wire fence. On a mound below the fence, new flowers blossom. These final images provoked really intense discussion. If I had ever needed persuading about the power of image in developing skills in inference and deduction, it would have been this experience that would have persuaded.

Some children decided that Rose had abandoned the flower, found her Mum and lived happily ever after. Some children read into the image that she had been shot by the soldier even though she was also German, the mound being her grave. All children discussed new life and its continuation even after the Holocaust. And only image can provide children with the opportunity to discuss intense, emotional issues from within their own understanding. Words have to spell it out too clearly to afford the opportunity for much interpretation. Could ten-year-olds have gained such an in-depth understanding of such a difficult issue from a print book?

My next ‘favourite’ is Varmints, by Helen Ward and Marc Craste. This is a touching story about the need to make time and space in our modern world. It feels cinematic, with see-through pages that create a soft-focus effect to some of the images. I thought I’d let a nine-year-old comment on this one for you:

‘One page is completely black. Probably the people’s minds were turned off. It doesn’t need words because I can make up my own story. The book goes from light when the Varmint is happy to dark in the middle then light suddenly comes back because the Varmints world has come back. You can read the book backwards because it goes from light to dark to light whichever way you read it. You feel like you’re in a film.’

And finally, Sara Fanelli's The Onion’s Great Escape – an amazingly powerful book which engages the reader in philosophical thinking at really deep levels. In case you’ve never read Sara’s books, you tend to form relationships with them rather than read them. This book is part poetry, part narrative and part philosophy. You also create your own new book as you release an onion from confinement. If you want to encourage children to challenge conformity and tradition, this is the book to share with them.

Sara’s work is typified by collage, a medium which she loves and which she feels that children engage with quite naturally. I spent hours when I first read this book gazing at the different collage materials, going off on thought tracks of my own. Then there are the scribbles which you can imagine to be anything... a very personal, visual experience. I haven’t read this book with anyone yet because releasing the onion will be a very special moment, for which I am waiting for a very special child.

So, words, who needs ‘em?

Well, we all do, of course. I’m not arguing for the abandonment of word books, merely an expansion of parental vision to allow for the enrichment of children’s reading experiences. But with the relentless, narrow view of reading and its mastery, which is the Emperor’s current new clothes, I don’t see it coming any time soon.

Published on March 21, 2013 01:00

No comments have been added yet.