Goodbye to the Black and White Church. Part 3 of 3.

We’ve been reading a historical document written in 1909. It’s a 100th anniversary retrospective of an old Southern church.

We’ve seen that in referring to the times of slavery, the writer has mentioned “the great interest in the welfare of black brothers manifested by our fathers.” He has assured his audience, “Ample provision was made for the religious instruction of this unfortunate class [the slaves].” We read the church rules for slaves in the last post.

Going further, the records show that before the Civil War this church received 184 colored members “on profession.” And this church was zealous about raising funds for the Southern Board of Foreign Missions. Both these facts suggest, possibly, that this church was not insular–that it was accepting of all people.

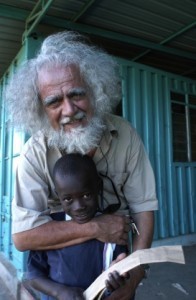

Father Kizito Sesana embraces a child. Father Kizito Comboni is founder of the Koinonia community association that brings together the abandoned children of Kenya. istockphoto.

Then came the Civil War itself. Did that earth-shaking event provoke discussions of the issues of slavery, morality, and religion within this church? After all, the entire nation seemed to be debating the justice or injustice of slavery. What did this church believe?

I found only two glancing references in this historical church document to the Civil War and its aftermath.

Here is the first reference:

“Although the services for the colored people under the shed were discontinued shortly after the war, the records show that quite a number were received into the church as late as 1867, and on the 18th of May of that year 12 were received, and two weeks later 7 others. On the 19th of October two others were received, but the days of Reconstruction had come and there were not more accessions. Indeed a large proportion of the colored members had already forsaken the church, and on the 29th of June, 1869, after having twice cited them to appear and show cause for their protracted absence from the church, the Session dropped from the roll the names of 87 colored members. There were still a number whose name were retained upon the roll, but while we find no record of it, they were in all probability dropped very soon for the same reason.”

This seems to mean that most freed slaves voted with their actions and left this church. Nothing here about the issue of slavery.

The other glancing reference is this passage about how white church members would gather before church services to discuss the progress of the Civil War:

“[To tell] . . . of the tense feeling and blanched faces as little groups gathered together and repeated in whispers the rumors of some great battle, and the loss of friends and loved ones; the intolerable suspense, long drawn out, often ended only by a confirmation of the worst fears. There is no hint of those sage discussions which went on out under the spreading oaks, as the movements of armies were traced, of the tactics of Lee and Jackson criticized: discussions that grew so absorbing at times that even when the strains of music from worshippers within reminded them that the service had begun, it was felt that it was needful to tarry yet a little, until some point which involved the welfare of the country might be settled. After the lapse of nearly half a century, how the scene comes vividly before us! Even now we can see that good old elder as he takes from his vest pocket that snuff box, and tapping the lid, opens and passes it to his neighbors as they stood around, and then after a flourish of the bandanna, and the conventional sneeze, the discussion would begin afresh!”

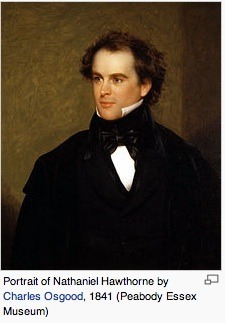

Nothing here about the issue of slavery, either. This scene of the “little groups” of parishioners is full of nostalgia and warm emotion—like a story by Hawthorne, that typical romantic American novelist.

By contrast, the account of the slaves’ disappearance from church seems factual and unemotional.

Portrait of Nathaniel Hawthorne by Charles Osgood, 1841 (Peabody Essex Museum)

On balance, it seems to me that this church history document is virtually silent on the moral or religious questions about slavery.

What does that silence say to you? Interpretations welcome.

[Thought question. No wrong answers.]

Destroyed during the fighting that engulfed Harpers Ferry in West Virginia during the Civil War, the ruins of St. John's Episcopal Church stand high atop the historic town and overlooks the Potomac River. istockphoto.