Turn, Turn, Turn

I’ve just been thinking about all the technical “revolutions” I’ve lived through and, indeed, had an active part in.

The first was the personal computer revolution. This happened – to me – in the late 1970s. As a psychology undergrad, I studied computing, just for fun. I learned programming in PDP8 assembler then went on to learn FORTRAN and Algol68. Computers really did fill a room in those days, even the small ones. I programmed an analysis of covariance to do the stats on my final year project in Algol68 on an Elliott 905. This beast had its own room. It had a massive 12k of memory and, to make it run, you had to feed punched tapes by hand through its optical reader; first a boot tape; then the language compiler; then the program you’d written and, finally, the data you wanted analysing. You generated these tapes on a teletype machine, which also typed the results when you fed the computer’s output tape into its reader.

The first was the personal computer revolution. This happened – to me – in the late 1970s. As a psychology undergrad, I studied computing, just for fun. I learned programming in PDP8 assembler then went on to learn FORTRAN and Algol68. Computers really did fill a room in those days, even the small ones. I programmed an analysis of covariance to do the stats on my final year project in Algol68 on an Elliott 905. This beast had its own room. It had a massive 12k of memory and, to make it run, you had to feed punched tapes by hand through its optical reader; first a boot tape; then the language compiler; then the program you’d written and, finally, the data you wanted analysing. You generated these tapes on a teletype machine, which also typed the results when you fed the computer’s output tape into its reader.

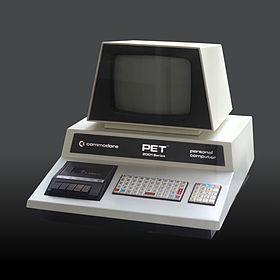

I bore you with all this detail because, mere months later, I’d joined a new psych department to do my PhD research and they’d just bought a Commodore PET 64 microcomputer that no-one had a clue how to use. The size of a typewriter, with a teensy TV on top, this little beauty had 8k of memory and used a really cool programming language called BASIC. I grabbed the machine, taught myself BASIC and started earning money writing statistical analysis software for the psych department. A year later, I got hold of a really hot piece of kit – an Apple II – and used it as the workhorse in all my experimental work, creating and displaying visual stimuli, controlling experiments with microsecond precision, and analysing the results. I loved that machine and it almost never had its lid on, I was so often interfacing new hardware to it. With a friend, I began selling my PC skills on the open market, building software for big companies like IBM, providing easily-accessible and user-friendly interfaces to their mainframe data and turning around projects in a small fraction of the time and cost that their internal programmers could achieve.

Those were heady, exciting times and, for those of us up to our elbows in silicon, we really did feel as if we were changing everything. But the next wave was already building. By the end of the 70s, the Internet had arrived and in the early 80s, I was working on hypertext systems and full of the excitement of designing arbitrarily complex, linked data structures for knowledge management and text retrieval. I remember having an email account in 1980 and having no-one to send an email to! A decade later, I had a similar problem when I got my first WAIS client and couldn’t do anything interesting with it. But, shortly afterwards, came Mosaic (later to become Netscape) and, when DEC’s Alta Vista search engine arrived in about 1995, the world just opened up. Oddly, it wasn’t until 1996 that I built my first personal websites but, within two years of that I was running the Asia Pacific Multimedia Centre for a large multinational IT company and building (more accurately, directing the building of) major corporate web businesses all over the region.

Those were heady, exciting times and, for those of us up to our elbows in silicon, we really did feel as if we were changing everything. But the next wave was already building. By the end of the 70s, the Internet had arrived and in the early 80s, I was working on hypertext systems and full of the excitement of designing arbitrarily complex, linked data structures for knowledge management and text retrieval. I remember having an email account in 1980 and having no-one to send an email to! A decade later, I had a similar problem when I got my first WAIS client and couldn’t do anything interesting with it. But, shortly afterwards, came Mosaic (later to become Netscape) and, when DEC’s Alta Vista search engine arrived in about 1995, the world just opened up. Oddly, it wasn’t until 1996 that I built my first personal websites but, within two years of that I was running the Asia Pacific Multimedia Centre for a large multinational IT company and building (more accurately, directing the building of) major corporate web businesses all over the region.

Corporate and Government Web apps saw me through to the end of my IT career – to the point where I gave it all up and became a writer. I wasn’t involved much with the mobile revolution that was taking off just as I was packing it all in, so the Web was probably the last big technology revolution I will actively participate in. Or so I thought.

By comparison to all that world-changing frenzy, becoming a writer has been quite a change of pace. Yes, I have deadlines still, now and then, and I still work, occasionally, with other people – editors and publishers – but, mostly, I sit alone and ponder. I’m not sure, but I may even be typing less now than when I was bashing out technical papers, project reports, quarterly reports, proposals, design documents, and so on, at a frantic rate, day in, day out. And yet I am still taking part in a world-changing technical revolution, albeit one that is meandering along at a rather leisurely pace. I’ve been involved with the rise of ebooks.

Back in the 70s, when I wrote prolifically on computing topics such as programming, artificial intelligence and communications, and the sale of such articles (along with my programming jobs) kept the wolf from the door while I was a postgrad, publishing was a dismally manual industry. I wrote on a computer from about 1978 onwards, first with Latex on a Prime mainframe, then using a word processor (WordStar on CP/M) but, to get my work to a publisher, I had to print it and post the paper to them. Not even the computer magazines could accept tapes or discs. It wasn’t until I was working with Macmillan in the mid-1980s that I could actually email manuscripts to my editor. Although, at work, we were doing research on knowledge-based hypertexts (including marked up video), the publishing world at large was stuck in the age of typewriters and telephones.

In 1988, I was a contributor to the 8th Edition of the Hutchinson Encyclopedia (I did all the computer and programming entries). This was published in a few formats, including an electronic version on LaserDisc. For those of you of tender years, LaserDisc was the forerunner of the CD. Imagine a 30cm CD that could play both sides and you’ve got the idea. (Don’t laugh, you’ll sound just as silly explaining flash drives as big as your thumb to your grandkids.) At the time, I was told that the LaserDisc version of this encyclopedia was the first commercially-published ebook. That may or may not be true, but it was certainly one of the first. And I was a contributor.

In 1988, I was a contributor to the 8th Edition of the Hutchinson Encyclopedia (I did all the computer and programming entries). This was published in a few formats, including an electronic version on LaserDisc. For those of you of tender years, LaserDisc was the forerunner of the CD. Imagine a 30cm CD that could play both sides and you’ve got the idea. (Don’t laugh, you’ll sound just as silly explaining flash drives as big as your thumb to your grandkids.) At the time, I was told that the LaserDisc version of this encyclopedia was the first commercially-published ebook. That may or may not be true, but it was certainly one of the first. And I was a contributor.

I pretty much gave up on publishing for the next 20 years. I almost completely gave up on my dream of writing fiction and focused on other things. I still published a lot of academic and technical papers but I stopped trying to get fiction published (except for the rare, disheartening foray) until I had an epiphany in 2008. About a year after that, I signed a deal with a New York small press to publish my novel Timesplash. It was a digital-only deal. When it came out as an ebook in Feb 2010, ebook sales were just 3% of the book market (by volume – not even by revenue) and this was a big, bold step, but I liked the idea of breaking new ground (new, even though my previous ebook had been published 22 years earlier!)

And I still do. That publisher was all wrong for my book and I soon persuaded them to give me my rights back. I then embarked on a new adventure of self-publishing and did pretty well at it. Meanwhile, I found an agent and tried to find a big however-many-are-left publisher. What she found was a new digital-only imprint of Pan Macmillan called Momentum, who were very enthusiastic about re-publishing Timesplash and its then-unwritten sequel. This is all very cool for all kinds of reasons (not least because Macmillan published my very first book – a kid’s science book about sensory psychology – all those years ago). And I still like the idea that I’m breaking new ground – this time in a wave of digital-only imprints from major publishing houses that I very much suspect could be the transitional phase for these houses to a completely digital world.

And it just dawned on me that this is my new tech revolution and I’ve been at the bleeding edge of it for over two decades as the major publishers slowly discovered the Internet, the Web, and the ebook. The difference is that I’m not making the technology for them this time, I’m putting my content out there on the front line, feeding it into the new platforms and experimental business models as a way of learning about and exploiting the changes afoot. It has something of the excitement of the earlier tech revolutions but the differences are everything, especially the difference in positioning relative to the mechanisms of change. I can’t wait to see how it all plays out.