Werewolves in Medieval History

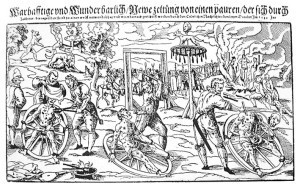

A print from 1589 shows the story of a witch/werewolf, Peter Stumpf (shown in wolf form attacking a child in upper left) who is caught and punished as shown.

Whether you’re more Team Jacob or “Werewolves of London” you know that werewolves are hot right now (both in sales, and apparently, in sex appeal). But their prevalence in the Urban Fantasy genre might obscure their long history. My eyes were opened to this history by a talk at the International Congress on Medieval Studies a few years ago, in a session promisingly titled “Hybrids and Monsters.”Gerald of Wales, in a 12th century geography of Ireland, tells the tale of a devoted and devout werewolf couple living like wolves, but with the hearts of Christians. When the wife is dying, the husband goes out at great risk to bring back a priest to administer the last rites. Some of my favorite quotes from this moving scene are when “the wolf said some things about God which seemed reasonable” and the wolf’s first words to the priest: “Do not fear.” These are also the first words spoken by the archangel Gabriel to Mary during the Annunciation, when he reveals that she will bear a miraculous child. So even then, werewolves were given a sympathetic nature.

This stands in apparent contrast to earlier views of such transformations in which the wolf represents the bestiality of the man. In the Medieval conception, the victim could become a wolf, but retain the reason and emotion of a man. The speaker, Jeff Massey, drew a parallel between hypostatis (the idea of God residing in man) with that of the werewolf (wolf residing in man). I dunno about that, but it’s interesting to think about.

The outstanding medieval werewolf appears in the Lais of Marie de France (another 12th century source) in the character of Bisclavret, a nobleman who is transformed into a wolf for three days every week. He is force to reveal this to his wife, who has her lover steal her husband’s clothes so he can’t transform back into a man. But even in his wolf form, he retains his loyalty to the king and behaves so graciously, that the king brings him back to court. After the gentle wolf attacks his disloyal wife (the first sign of violence in the beast), the truth is revealed, and Bisclavret is brough clothes so he can become a man once more.

In both of these cases, we don’t know how the good people were afflicted with their fate, but other period tales and superstitions suggest the opposite of Bisclavret’s solution: it’s not the clothes that make the man, but the skin that makes the wolf. In these cases, the werewolf, often a witch, dons a wolfhide in order to deliberately become a wolf and go about ravaging the countryside. In most cases, this results in the witch/wolf eventually being hunted down and slain in wolf form, and thereupon, transforming back. The contrast between this behavior, and that of the good wolves, who apparently succumb through no fault of their own, suggests that the beast resides within us all–and can be managed if you retain your reason. If, however, you revel in the beast, a sorry doom awaits. Wikipedia has a nice selection of methods by which men become wolves in superstitions of different lands.

I recently found a reference to werewolves in the Volsungasaga of 13th century Iceland. Also heard of an Arthurian story about a former werewolf called “Gorligon.” Do you have some good references for early werewolves? Please pass them on!