Occupy Steve: How to Flesh Out Your Characters

Are you revising your novel during our “Now What?” Months? One of the toughest summits to climb can be breathing life into a character; Elizabeth Lyon, a longtime book editor, tells us how to fill their lungs:

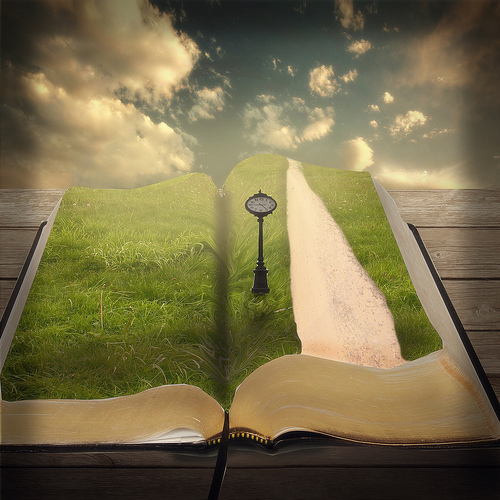

Within the mass of pages you produced, some passages are breathtaking in how well they are written, even more have “potential,” and a number are destined for replacement. The prospect of revision may feel as though you’re anticipating a brutal climb up Mt. Everest without rope, ice axe, or map.

Sherpa guide Elizabeth Lyon at your service. First, breathe. Second, remember that you won’t be facing the terror of the blank page. Third, characterization is everything. Begin revision here. In the beginning, your characters were actors reading their lines. By the end of revision, they must become so real that your readers will love them, or fear to run into them on the street.

Transforming actors into unique and complex characters is the part of writing that most often derails the finished product. Characters with emotions keep readers biting nails, sighing, chortling, wishing, and tweeting, “You gotta read this book.” Chances are your draft is long on action. Hot writing produces pages, not contemplative pauses. So how do you turn your player pieces into three-dimensional “humans”?

Reset your tempo to largo; read page one and let yourself sink into your viewpoint character’s body. What is he or she sensing? Think of the usual: sound, smell, temperature and touch, taste, and sight. Most of us write early drafts visually, seeing the movie in our heads and translating these pictures into words. Fast writing can lead to over-reliance on descriptive sketches that are more camera-like than personal.

Let’s call your character Steve. He’s standing on a side street in downtown Seattle. Where specifically? GPS him. Look around—is he standing on the cracked, uneven sidewalk outside Burger Brothers? Near enough to hear the baritone blasts of the cruise ships at the pier? Or notice the rain pinging off the aluminum awning? Suddenly his attention is grabbed by an old green Pontiac roaring through a curbside puddle sending a spray over his secondhand boots and threadbare jeans. Damn it. The door opens behind him, and Steve’s stomach rumbles as he catches the smell of French fries sizzling in hot oil.

Be specific and the reader will slide right into the body of your character, eager for a vicarious ride.

Okay, we have Occupy Steve. So far so good. What is he feeling and why? Feelings supply motives, and thoughts provide a plan of action. Something is always happening to your characters, and he or she must react. If your character is mad, how mad? Miffed? Homicidal? How would he or she display fury? By kicking the chair over? Every heartbeat like flint on flint sparking a blaze of expletives?

We editors like to advise, “put emotions on the body.” Visceral or physical reaction first, then emotion and thought. After you’ve added reactions appropriate to the action, weave in thoughts—memories, concerns, and decisions—whatever drives your character into the next action. In other words, characterization drives plot.

Let’s revisit poor Steve. The door of the restaurant flies open and a man exiting slams into Steve. Action. The blow knocks the air out of his lungs and throws him hard on his left shoulder, already bruised badly. The pain pulses out blasts of hurt that light a blowtorch of rage. Not even a ‘sorry, mister’. Invisible. Nobody wants to see a homeless vet, or an addict, or a beat-up old man standing in the rain hoping for a handout. Steve struggles to his feet and stares after the well-dressed man. Steve clutches his shoulder and limps down the sidewalk. He’d catch the S.O.B. and make sure one man would never forget him.

Once you have occupied your characters, your reader will. They’ll vicariously experience the visceral and emotional actions and reactions, as well as the driving motives and needs of the characters. You’ve breathed life into the thinly draw actors of your fast draft. The reader now cares about them, and cares to know what happens next.

Read slowly, then stop. Look. Read slowly, then stop. Listen. To revise is to relive your story as Steve, as each and every one of your characters. Moment by moment. To the summit. The finish line.

Elizabeth Lyon has been a book editor since 1988. She is the author of many books for writers including the acclaimed Manuscript Makeover, and a soon-to-be released e-booklet series on writing.

Photo by Flickr user ClaraDon.

Headshot by Eric Griswold.

Chris Baty's Blog

- Chris Baty's profile

- 63 followers