The Hardest Book I’ve Ever Written

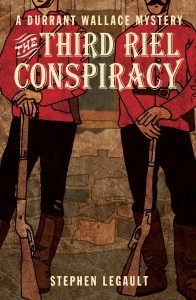

The hardest book I’ve ever written is set to be released in the coming weeks (mid March, 2013). The Third Riel Conspiracy is the second novel in the Durrant Wallace Series of historically themed murder mysteries, and is my seventh published book. It was hard to write in several ways: the research was hard; the writing process was hard; and the editorial process was by far the hardest I’ve gone through.

The hardest book I’ve ever written is set to be released in the coming weeks (mid March, 2013). The Third Riel Conspiracy is the second novel in the Durrant Wallace Series of historically themed murder mysteries, and is my seventh published book. It was hard to write in several ways: the research was hard; the writing process was hard; and the editorial process was by far the hardest I’ve gone through.

The book follows Durrant – the one-legged North West Mounted Policeman – from the newly minted town of Calgary to the battlefield of Batoche at the apex of the Northwest Rebellion. He arrives during the chaos of the final day of the four day battle to find that a man has been murdered in the Zareba, the African inspired fortifications erected by the Northwest field force. A Métis man is in irons for the crime, but Durrant suspects that there is more to the murder than simple revenge.

When I started working on the Durrant Wallace series in 2007 I quickly plotted out the first three or four books in the series. This is how I’ve approached all of my writing projects. I don’t think in terms of single books, but narrative arcs that continue over several volumes. The first book in the series, The End of the Line, was published in the fall of 2011, and by the time it came out I was already neck-deep in the second volume.

That was the first thing that was hard: the research. Writing historical fiction isn’t like penning a regular mystery novel. In addition to mapping out the plot of the story and ensuring that the settings are accurate – something that I think is very important – there is the additional challenge of matching the storyline with the actual events of history.

In the case of The Third Riel Conspiracy, that meant doing a great deal of reading about the Northwest Rebellion and actually visiting many of the places in the book. Starting in the summer of 2009 I began reading dozens of books on the history of this seminal period of Canada’s development. The roots of the second Northwest Rebellion were in the uprising of 1870 in Fort Garry so I had to reach back that far in my research. The conspiracies that form the backbone of the novel’s plot are based on actual political skulduggery at the time so I made a chart of the real life machinations afoot and then changed them to meet my needs. (Interestingly Riel and his colleagues’ sentiment in 1885 was that “the west wants in;” 100 years later the Reform Party would use that same sentiment as a motto but with a much different result.)

I tried my best to understand the various motivations – religious, social and political – for the return of Louis Riel from Sun River, Montana to the Saskatchewan Territory in late 1884 and use those to create suspects for the murder. This gave me the chance to explore each of these themes in turn throughout the novel. In addition, I wanted to tell the story of the Battle of Batoche, a fascinating and often overlooked marker in our nation’s history, but didn’t want to reduce myself to mere exposition. Instead, I selected four key suspects and through Durrant’s interrogation of them revealed the events of the four-day conflagration.

I made dozens of pages of notes and charts and printed maps of the battleground and created a detailed timeline that placed my characters into the context of the real action of the day. As is my custom, I created a thorough outline of the book – what happens in each chapter, and how the characters interact – before I started writing. I made a chart of all the suspects – and there are a fair number in this novel – and then created a list of red-herrings that would be used to distract the reader from the actual killer.

All of this took place in the summer and fall of 2009. It was obvious that I would have to visit Saskatchewan, so instead of taking a trip to Utah to ride our mountain bikes, Jenn and I went on a four- thousand-kilometer road trip from our home in Victoria BC to the battlefields of the Resistance: Fort Pitt, Frenchman’s Butte, Fort Carlton, and finally Batoche National Historic Site. My wife is a good sport.

Photo taken from a grown-over riffle pit on Frenchman's Butte, looking toward the ground held by General Strange during that skirmish.

This on the ground research was vital. While I had a vague sense of the landscape from reading the historical accounts of the conflict, seeing it, feeling it underfoot, breathing in the prairie air, was critical to being able to write about the place, and for understanding the origin of the uprising. It was very much about the land and the Métis and First Nations relationship with these beautiful places.

When we got back from the trip we were distracted by our upcoming move back to the Canadian Rockies (we had bought a house in Canmore on the final leg of the journey) and writing The Third Riel Conspiracy got put on the back-burner. It would be a year before I took it up again.

That was the second thing that made writing this book so difficult: the time lapse between research and writing. I’ve outlined some of these problems in more detail in the section of my blog I call “deconstructing draft one.” The main problem was that my notes, while plentiful, left me guessing in places about what I wanted to happen, to whom, and when. I didn’t have to start over once at the keyboard, but I did have to reconstruct some of the plot.

Reconstructed gate at Fort Pitt.

The next challenge was fitting the actual historical events into the timeline I had constructed for my characters. Durrant Wallace is a sergeant in the Northwest Mounted Police, but because there was no official investigative branch in the NWMP, he operates outside of his jurisdiction. He reports to Sam Steele, who during the period of the Battle of Batoche was more than 300 miles away, tracking the Plains Cree and Big Bear as they fled towards Frenchman’s Butte and Steele’s Narrows. I had a critical exchange that I needed to engineer between the two men, but they couldn’t just text each other; I had to get them in the same place at the same time. Steel stopped at the burned-out Fort Pitt at one point, so that’s where the scene would take place. I had to jimmy dates and Durrant’s progress in the investigation to allow him to arrive at Fort Pitt the same time Steele would. It worked, but it took several tries to get the dates aligned.

Similar challenges occurred with Leif Croizer, who was the Deputy Commissioner of the NWMP at the time. I took some liberties there.

Undoubtedly the greatest challenge with writing the book was how to address Louis Riel. More than one-hundred and twenty-five years after his execution, Riel remains one of the most contentious characters in Canadian history. One possible motivation for the murder in this book was the complex web of politics that surrounded his life, and death. I figured that having Riel as an actual character in the book would be a flashpoint for controversy, but only he could have the critical piece of information that Durrant Wallace would need in order to find the real killer in the novel.

You’ll have to read the book to judge how I handled this challenge.

The cemetery and Mission church at Batoche; the scene of heavy fighting on day one and day four of the battle, and where the Métis killed during the fighting were buried.

The final challenge for this book (so far) occurred when I sent it to my publisher, and the book went through the inevitable story-editing hell. I love my publisher, and I love my editor. We’ve worked together on five books now, including The Third Riel Conspiracy, and the upcoming Glacier Gallows, and without a doubt they have made every single one of those books better. But it isn’t easy. Buy the time I press send on another novel, shipping it off to the publisher, I’ve spent several years with the book. I’ve dreamt about it; I’ve sweated bullets over dialog; I’ve made painful decisions about, as Bob Seger says, “what to leave in and what to leave out.”

So I’m attached. I try not to be, but inevitably when the edits start rolling in, I realize that I am.

The Third Riel edits were very difficult. I’m not going to go into details, because it’s water under the bridge, but suffice to say that for the first time in decades I seriously considered stopping writing. It lasted for a few weeks. On a good day I require a pretty heavy hand when it comes to edits, but The Third Riel was by far the most red ink I’ve ever seen. I plowed my way through, frustrated and a little despondent, wondering how it could be that seven books into my writing career I was still making all the same mistakes. I got through them, and with a pep talk from my publisher, got excited once more about writing. But there were some pretty dark days during the editorial process for this book.

The book should be back from the printer this week, which means soon I’ll get my shipment of complementary copies, and will experience once more the excitement of opening the box, smelling that fresh-printed-ink smell, and get to fondle a copy of The Third Riel Conspiracy for the first time. I know from experience when that happens all the challenges of creating the book will dim and I’ll get to feel the excitement of holding this creation in my hands.

I don’t know if this being the hardest book I’ve ever written will equate to being the best book I’ve written. I’d like to think that’s true for every book I write, which would mean that my writing is always improving. That’s for you to decide.