Giving Back: Interview with Annabel Morgan

A few years ago, before I was published or had an agent, I made the pact that I would donate a chunk of whatever I earned from my writing to charity. I’m a firm believer in giving back, and it gives me great pleasure to be able to present this interview with a performer from this month’s charity (for more information check out my charity link above:

During my time with The Circus Village, I had the opportunity to get to know Annabel, an amazing girl from South Africa who works for a very special relief organization, Clowns Without Borders South Africa (CWBSA). One afternoon, she graciously sat down with me in the cafe tent and allowed me to interview her.

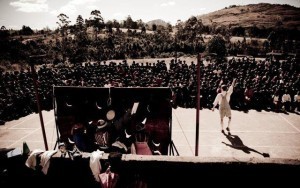

provided by CWBSA

Alex: First off, thanks for talking with me about CWBSA. Could you briefly tell up about the organization and how you became involved?

Annabel: Gladly! CWBSA is a humanitarian organization dedicated to bringing emotional relief through laughter and play to communities in crisis in southern Africa. I was ‘clowning around’ in Swaziland when I heard about CWBSA and I thought it brought together everything that I love; the performance and healing aspects through creative expression, playing, and working with children. I came from a performance background, but it wasn’t enough to just perform onstage. CWBSA was my perfect job. It was very serendipitous; I mentioned to a colleague that I wanted to work with them and he said they were doing an audition the next day. I dropped everything and went—I knew this was the work I was destined to do. This was early 2010, I believe.

Alex: From your experiences, what are the effects CWBSA has on the local communities?

Annabel: It’s hard to measure the effects. You just feel it; when the clowns enter a community to do a show, there is an excitement in the village—it’s a time of celebration. We have to be really organized otherwise it becomes chaos; sometimes we perform for over 2k children. I think the best way to describe the effect it has is to just share a few stories.

There was one show we did in the eastern Cape last year, and there was a routine where we needed a volunteer. I picked an 8y/o boy, and during the routine he was one of those volunteers who really just made us look like clowns. It was fantastic. Afterward, the principal came to talk to us and. He wanted to thank us, not only for relieving the stress of the teachers, but he said that the young boy was HIV positive and suffered from severe headaches. He’d been out of school the last two weeks and showed up to just that day—when the principal asked the boy how he felt after the performance, the kid was all smiles and said he felt amazing.

Those are the kind of stories you hear. Apart from the obvious effect of crowds laughing and jumping off their seats, it’s those individual stories that make you realize you’re just dropping a stone in the water; the ripples are huge. So many of these places are torn apart by poverty or HIV and there is no relief—especially not emotionally. We’re sometimes the only time these people—kids and adults—have to laugh or play or just be happy together.

Sometimes we go back to communities and find out that our songs and skits have spread for kilometers in these rural areas—out there, people don’t have cars, they always walk. It shows our work is really reaching the community in big ways.

Obviously, that’s the performances. When we go back (for ten days in the Njabulo program) we can talk about how things are or are not changing. If they aren’t changing, we problem solve and open up to group discussions so the community can find solutions. For example, one of the most powerful things I’ve heard was a 54 y/old woman caregiver saying ‘ before you came, we thought it was our time to die. Now, we feel alive again.’

provided by CWBSA

Alex: Could you tell us more about the Njabulo Program?

Annabel: It’s an arts-based intervention program. We go to a community for10 days and work in the mornings with the caregivers and the afternoons with the children. We use drama, storytelling, movement, song, play and mindfulness with the main intent to nurture and strengthen the relationship between the guardians and the children. In this instance, caregivers is the term we use for the person responsible for the child—it could be a grandmother (if their parents aren’t alive or they don’t live with their parents), aunt, distant relative, or just someone in the community. Because there’s such a huge crisis of orphans, sometimes a member of the community with no connection has to take them in. Sometimes the guardian might already be looking after 6 or 7 children. It’s a huge responsibility, especially if they’re a grandmother—have aches and pains but still have to look after the kids. There’s no time for play. A caregiver might also be the oldest kid in the family—14 or 15, we call these child-headed households.

For our impact to be the most sustainable, we want to influence that child/caregiver relationship. We don’t say “we’ll teach you how to have a better relationship with your child.” We literally just come to play. That said, there’s always home practice: the real work happens in the evenings of those ten days, when the kids and caregivers start sharing stories or singing songs they’ve learned through us.

With the guardians, we facilitate a lot of discussions about exercises we do and how they might be relevant to their lives; that way they’ll notice changes in their children and their children will notice changes at home.

Exercises might include something we call ‘sculptures,’ where they have to sculpt their partner into an emotion: anger, hope, love, pain etc. From that you can see a lot about the person—those who find it easy to sculpt hate, hard to sculpt love, etc. With the guardians, once they’ve sculpted a picture of anger, we ask them to move around and look at the other sculptures and ask how it makes them feel. From there, it leads into a discussion about feeling unapproachable by their children, feeling like monsters, etc. Another exercise is a flying program—literally being ‘lifted up’ by the community. Again, so often these people feel alone with their struggles; we try to build the feeling of community. They aren’t alone, and that can be a tremendous relief.

Alex: Can you tell us about your skits?

Annabel: Gladly! Our shows are never message based. But we like to create routines that are about everyday life, that are familiar, so often the audience sees a message or gets relief from them. After all, laughter is the best medicine.

Clowning is all about status and relationship. For example, our lunchtime routine: 4 clowns and one lunch bag with one banana and one juice inside. So in that group of 4 clowns, 1 is the highest, 4 is the lowest. So in the skit, the food gets stolen down the line and eaten in funny ways, until clown four gets just the peel. The same happens with the juice. Then a hankie goes down. Often the children find it very funny…because they’re laughing out of identification. They know how it feels to be the last one in the family to get something, or not get something. When we have a clown funeral, although it’s obviously something very prominent in their lives, it’s still somehow cathartic for them to laugh when they see the clowns mourning the death of a balloon.

I read about the CWB expedition to Japan after the tsunami. The clown talked about the laughter, and how it was abnormally loud—it was a real relief for the communities affected by the disaster. It was as if their laughter was so loud not just because it was funny, but because they were using the laughter to release a whole lot of other emotional stuff. It creates big change.

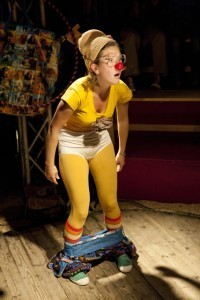

provided by CWBSA

Alex: You said earlier that all the clowns have their own personality. Could you tell us about your character, Banana?

Annabel: *laughs* Oh, Banana. Em, she changes with every costume she gets. Essentially, she’s a really ‘cool clown,’ or at least she thinks she is. And she loves to dance. She’s a magnification of my personality—she’s not something I ‘put on,’ but is something I draw from and magnify. A clown is very honest, and only works when it’s truthful .Clowning is bout constraint and release—moments of extreme doubt and confidence, etc. It’s just the beginning of this clown journey for me. They say you’re only a really good clown if you’re old.

Alex: Thanks so much for sharing all this. Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Annabel: Yes, just one little plug. If you appreciate the work that we do or want to learn more, please donate or check out www.cwbsa.org

A.R. Kahler's Blog

- A.R. Kahler's profile

- 362 followers