Morris Award Finalist Interview: emily m. danforth

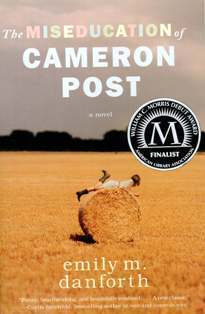

The Miseducation of Cameron Post written by emily m. danforth, published by Balzer + Bray, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

The lowdown on tMoCP:

When 12-year-old Cam learns that her parents have died in a car accident, her first reaction is relief that they will never know that just hours before she was kissing her best friend, Irene. Shortly after the funeral, her conservative aunt moves to Miles City, MN, to help Cam’s grandmother with the caregiving, but all the churchgoing and discipline they can marshal throughout Cam’s teen years can’t prevent her from exploring her sexuality further, finally falling for Coley Taylor, a “straight” girl who wants to experiment. When they eventually get caught, Coley tells all, blaming everything on Cam, and Aunt Ruth sends her niece off to God’s Promise, a conversion therapy school and camp. It is here that Cam meets gay teens like herself, and she begins to deal with the guilt and trauma of her adolescence, not through the pious teachings of the camp but through the love of her friends.

Because of my past relationship with the Morris Award, I was recently allowed to barrage my friend emily m. danforth through email and text message to obtain the following interview. If you don’t already love her, you soon will.

You can stalk her here: @emdanforth

Here: http://www.emdanforth.com

Or here: http://somuchflotsam.tumblr.com

Enjoy!

1.) We all know that The Miseducation of Cameron Post is your debut novel, but was it the first novel you’d ever written? How would you describe the experience of writing it? (Do you feel it came naturally to you, or did you struggle/were you accustomed to other types of writing?).

First things first, JC-dubs, thank you for interviewing me here as part of this very fun Morris Nom tradition. I’m tickled to be participating in it. I only wish that it also came with some sort of creepy induction ceremony that takes place at night on an ivy-swathed brick and stone college campus somewhere here in the northeast, a ceremony that involves blindfolds and drinking strange substances from a communal cup and possibly group tattoo and Pacey Witter from Dawson’s Creek …Or wait: does it potentially include those things and I just can’t know about them yet? Don’t tell me. I can wait.

tMoCP is both my debut novel and my first-novel-ever: the first I wrote or attempted to write. Working in the novel form felt pretty much like coming home, really, even early on in the drafting process, before I necessarily knew what I was doing or where the book was going. I was a student in a couple of grad programs (focused on creative writing) while working on tMoCP, and because of my enrollment in the workshop portions of those programs, I’d become accustomed to writing, for years, really, short stories. This was true in the undergraduate creative writing classes I took, too. For all kinds of reasons it’s just easier to workshop a 15-page short story than a chapter or scenes toward a novel. And writing short fiction also seemed really productive, at the time, because the idea was to write, workshop, and revise those stories and then send them out for publication in various literary magazines, hopefully building substantial pub creds that way. And lots of my fellow graduate students were very adept at this process. The thing is: I was never very good at writing short stories. I just don’t think that form suits me particularly well, and it certainly doesn’t speak to the reasons that I wanted to study (and write) fiction in the first place, which have absolutely everything to do with novels—usually fairly long ones. I love to read short stories, but personally I think that I’ve only ever written 3 that are any good at all (and one of those is maybe only 65% good.) And those stories came to me almost fully formed at their inception: I saw the whole story, how it would work in terms of approach, content, style, and I just sat down and wrote it and it basically ended up working as a story (with very minor revision). But, I mean, that’s true of only 3 (2.65, really) stories out of the dozens and dozens and dozens I’ve made attempts at over the years. Not such an impressive record.

Anyway, while all of that work writing shorter forms of fiction was ultimately a very good thing for me in terms of developing technique and learning to read like a writer, to recognize craft and its various usages in a piece of fiction, it never inspired me the way that working on a novel does. So while I wouldn’t say that tMoCP came easily, necessarily (there were plenty of stops and starts and things to fiddle with along the way), it did feel like it was absolutely the book, the story, that I needed to be writing, that I most wanted to be writing—and I recognized that early on. I think most of my general approaches to storytelling are just best served by the novel form.

2.) What is it about coming-of-age stories that intrigues you? Do you think you’ll always be interested in this kind of story, in one way or another?

I think if you’re not coming-of-age in some way, always, then you’re stalled—stagnate. It’s tempting to try to say something pithy, here, like: In the end, every story is a coming-of-age story—but that’s pretty simplistic and not all that interesting, either. I know I have a more expansive “take” on coming-of-age than lit purists or scholars of the bildungsroman allow for, but so, so many novels that I admire, novels that made me want to be a novelist, can, I think, be read in satisfying ways as coming-of-age stories. Sure, usually when people use that term they’re talking about transitions that move a character, a person, from childhood/adolescence to adulthood (this is almost always true when we talk about YA), but that doesn’t mean that coming-of-age can’t speak effectively to lots of other scenarios, other kinds of narratives. One of the things that lots of fiction does, particularly character-driven fiction, is chronicle an extensive process of change that occurs in the novel’s main character. Traditionally, the coming-of-age novel just happens to do that with younger characters who are awakening to a certain level of maturation or self-awareness or identity-formation and then either embracing or fighting against those changes (or, often, both: fighting against and embracing). And everything about these processes is naturally heightened for teenagers because they’re completely new and therefore so often feel fraught. So, to answer your question: I absolutely wanted tMoCP to be, at its core, a great big coming of age (or coming of GAYge, as I’ve joked before) novel. I wanted it to follow this character, Cameron Post, for several years of early and mid-adolescence as she settles into herself, figures out what that it even means to be Cameron Post—what are the options, who is that person, or who might she be? And, most importantly, I wanted my novel to work within this first-person literary tradition, one that offers a chronicle of a character’s experiences with certain rites of passage typically unique to adolescence.

And yes, I will always be interested in reading coming-of-age novels—particularly given, again, that I think pretty expansively about just what that means. And thematically, sure, I’m certain I’ll explore some of these same themes in my future novels, but I don’t know that I’ll again write a book that’s framed so specifically as a capital C Coming-of-Age story. I feel like I’ve done that already, and have done it in a way that, for now, I’m really satisfied with. There are countless other approaches to writing fiction about adolescence (and adolescents)— particularly in terms of thinking about how to structure a novel—that I want to tackle now.

3.) You’ve said before, in previous interviews, that your major goal when writing Cameron Post was to “honestly portray [your] character’s experiences with as much nuance and depth as possible.” Do you feel like you told the story the way you wanted to tell it? Would you do anything differently, having lived with the novel for so long now?

Did I really say that was my “major goal” in writing the novel? Did I use that phrase—major goal? I believe you—I believe that I did, I just feel pretty sad/cringe-y about it now. I think I had lots of goals when writing this novel. Wait, I don’t even like the word goals when it comes to my novel and what I was or wasn’t attempting to get at with it. What gives, JC-dubs—why you trying to set me up for failure, here? Am I soccer player or a novelist? (But then there’s the sweet fact that I’ll always love you JCW. You know it’s true.) I think, I hope, what I was talking about in whatever interview you’re quoting me from, is just what I think all character-driven, representationally-realistic fiction does or attempts to do—and no doubt tMoCP is character-driven, representationally realistic fiction—and that’s make the characters feel as fully imbued with all their humanity as is possible on the page. I don’t know if I succeeded at that completely (maybe not with Aunt Ruth, say, or Lydia from God’s Promise), but I sure tried to revise my way to that place. I want readers to feel like these are walking, talking people—not props, not puppets for the plot or some didactic agenda, certainly not one-dimensional cut-outs for me to manipulate in scene. But there are more elements than just character development bound-up in making all of that happen, of course—the idea is creating a complete and convincing world on the page and then, you know, making shit happen within that world. I mean, I was absolutely as concerned with developing sense of time and place in tMoCP as I was with getting the characters inhabiting that time and place to feel authentic. I don’t know how to remove one from the other, or to prioritize one over the other—those things have to work in concert.

As for changing things—shoot: I’ll always want to do that, I think. I’m just one of those writers. I can’t point to a specific scene for you—not right at the moment, anyway—but sometimes when I’m giving a reading, say, I’ll think about how I might have worked a sentence or a moment differently, or added this character detail, finessed this line of dialogue, whatever. The other thing is that there’s so much of Cam’s story (written, I mean—pages of it) that’s not in this book. I suppose that sounds incredible to people who look at its current 500 page heft and want to hit me with a stick (or maybe just with the book), but it’s true. I know where Cam goes immediately after the novel’s closing scene, and what’s more: I know where she goes after that scene, and the next. And a lot of that material is already written and revised (though not quite all of it). Maybe someday it will be published, but I don’t think I’d ever want it as a separate book 2. It’s not its own novel is the thing. In my dream scenario, instead what would happen is they’d reissue this novel, tMoCP, but it would have like 300 pages more than the version people have now. That’s all. It would be the super-sized version—that’s what it would be.

4.) Since its release, your novel has been met with much critical acclaim. Can you speak a bit about how it feels to be recognized so publicly for something like writing, which is, in my opinion, such a personal, private thing?

Well, you know, it feels both wonderful and also too public sometimes, too exposed, which has been an uneasy combination for me to settle into, but it’s likely one that doesn’t really go away. It’s a combination that speaks to the differences between being a writer (private) and an author (public)—and whether you like it or not, once you publish your book, you’re definitely both of those—both hats are hanging there on your coat trees, my friends, and you’re expected to put one or the other on at various times. (Though not usually both at once). It’s not that I don’t like that public side of things (I teach, after all, and that’s certainly part performance), but it doesn’t come as naturally to me as the writing part, and I still wonder, all the time—am I doing this “author” thing right? How might I do it better? It really is wonderful to have anyone, anywhere, involved with my novel—reading it, thinking about it, saying something to someone about it. It’s still, in some ways, something I have a hard time quite fathoming, even. It all still feels very new in that way, which I love, the newness of it—I do—but that also means that so much of the process is unexpected, and so it sort of gets at what I was saying when I was talking about coming-of-age as an adolescent—simply the continued newness of this process, if you’re a debut novelist, the unexpectedness, it can feel kind of fraught, I guess—even if it shouldn’t, or if it’s not reasonable for it to feel that way. Does that make sense? Maybe it’s a little like waiting for the other shoe to drop or something. Or maybe it’s just, again, the combination of these two very disparate states of being—wholly private, plopped down at a computer, muttering about scenes for days on end; and then tweeting, and giving readings and blogging and out there being an “author.” Other people manage the two with a kind of elegance and ease (or it seems that way) that I envy no end. I just putter about between them like an old woman without her glasses who’s looking for her cat in her neighbor’s rose garden, bumping into the wheelbarrow occasionally, stepping backward and mashing the prized Damask on the trellis. It’s mostly a pleasant sort of bumping-about, but it’s not very graceful.

Lightning Round: Answer in as few or many words as you like. Who needs rules?

-What’s your favorite song? Can you sing it well?

Does anyone really have just one favorite song? I’m impressed by that. I do not. I have favorite songs on certain days or for certain occasions—I have lists of favorite songs by artist or genre or theme, year, certainly, but no singular, favorite song. However, I sing Bonnie Raitt’s portion of the live, acoustic version of her very sad duet with John Prine, “Angel From Montgomery,” pretty well, I think: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1T5NuI6Ai-o. (On certain days.) And I can do a mean “Sandra Dee” (from Grease) at Karaoke. But then, I suppose, so can most everyone else.

-If you could have written anyone else’s book, which book would it be and why?

Michael Cunnigham’s novel The Hours. For me, it’s a perfect novel, and if I’d written it I think I might have just ended things there and said, Done, suckers: I am done. You see this thing I just wrote? Yeah? Well that’s it. There it is and you’re welcome. (Of course, lucky for all of us, Michael Cunnigham, is not a total tool bag and so he has not acted this way and continues to write other beautiful books.)

-You’re an Assistant Professor of English at Rhode Island College. So, tell me, do you think you’re better than me?

This is how you’re going to end this interview, JCW? Really? This is the note of your choosing? Fine. I mean, my options here, clearly, are to respond with one of the following answers to your horrible question:

1. No I do not, but your inferiority complex is showing.

2. Yes I do, of course, but not for the reason you mentioned.

3. What did the people of Rhode Island College ever do to you? You gotta problem with all Rhode Islanders, JCW, or just the people who work at or attend one of its public institutions of higher education?

However, I won’t do that. I won’t stoop to that level. I’m ashamed of you, JC-dubs. I thought we’d declared a truce of our great literary feud to conduct this interview, but it seems that I am mistaken.

All literary feuds aside, emily m. danforth is about as awesome as they come and so is her beautiful novel. So, good luck to her and her fellow finalists!

-C.

John Corey Whaley's Blog

- John Corey Whaley's profile

- 903 followers