My Back Page(s)

This is an afterword I wrote for Fringe-ology. My editor suggested the story here blunted the ending, so it wasn’t published. But I’m sharing it now, in a slightly revised fashion, because this bit reflects so positively on a claim put forward by Sam Harris, the only major new atheist thinker who allows that “spirituality” and “religion” are not the same thing.

AFTERWORD

As a little boy, my parents led me by the hand, every Sunday, into the hushed, reverential atmosphere of the Catholic Church. These regular trips into a beautiful room where everyone confessed to a belief in the unseen made a huge impression on me. Fact is, I loved those days. But in writing Fringe-ology, I realized how far I’d traveled.

The realization of the distance between that boy and this man hit me most  profoundly when I spent a long day sitting and watching YouTube videos of various talks given by Sam Harris. The subjects he tackled ranged from neuroscience and terrorism policy to the atrocities of religion. In one video, a debate on religion, he put forth the following observation: Come on, he told his opponent. You and I could make the Bible a better book right now.

profoundly when I spent a long day sitting and watching YouTube videos of various talks given by Sam Harris. The subjects he tackled ranged from neuroscience and terrorism policy to the atrocities of religion. In one video, a debate on religion, he put forth the following observation: Come on, he told his opponent. You and I could make the Bible a better book right now.

Harris, one of the most famous atheists on the planet, quickly rattled off some sections he would edit out. And I sat there, thinking, “You’re damn right.”

A moment later I was laughing at the audacity of what I had just thought: Edit the Bible? I had entered into this project with the goal in mind of bringing people together. But editing the Bible would inherently be a divisive exercise, driving away all those who believe every word on every page came straight from God.

As the days passed, however, the idea didn’t leave me alone. And I had to admit: It actually fit with the larger argument I make in Fringe-ology, It reflected my goal of urging people on both sides of the culture war to step back, often, and view the existential questions with which this book opened—Who are we? Why are we here? Are we alone in the universe? Is there a God? And what happens when we die?—for what they are: Open questions. Unanswered questions.

We have our beliefs about what the answers to these questions might be—some based more or less firmly in science. (God knows, I have mine.) But firm knowledge, ultimate knowledge, eludes us. And it’s my position that we need to view our lack of knowledge as important—as meaningful. All over the planet, people choose to honor some particular religious deity or perhaps a materialist, scientific worldview. And so I came to see Harris’s suggestion as an exercise that might actually rally us all a little closer together.

I wonder, if believers read the book in that spirit—that the Bible might be bettered—what (for lack of a better word) revelations might come. I suspect that if believers of various religions each read their sacred texts with a red pen we might quickly find ourselves on a very different planet, one in which words like “love” and “faith” remain in abundance while “vengeance” and “judgment” are winnowed away by many.

I also wonder: If nonbelievers read these books with an eye toward what words to keep, would we be surprised in the end to find so many pages still intact?

There is only one way to find out, of course. But whether people choose to take on this kind of exercise is up to them. As I put the final touches on this manuscript, in the fall of 2010, I am preparing to return to city journalism—crime, courts, politics. I ventured so far from my usual territory because I wondered how standard journalistic practices might perform in answering the most fundamental questions human beings ever face. I wanted to settle the personal business associated with the Family Ghost. And I found the ongoing culture war between science and religion so counter-productive and tedious that I simply could not keep silent. But upon further reflection, I also did it to satisfy the little boy I mentioned above—the little boy who was led into those beautiful, intimidating Catholic churches.

He loved those Sundays. But over time, as his understanding grew, he felt panic-stricken at the Priest’s pronouncement: “We believe in one Church.” He looked at people he saw in the street, the grocery store, school, and wondered if they might burn in hell for not going to the Catholic Church. For a long while, he kept his concern to himself. But finally, the thought of all that suffering was too much for him. And so he went to his father and asked: “Is everyone who doesn’t go to a Catholic church going to hell?”

“No,” his father smiled. “That’s not what we believe.”

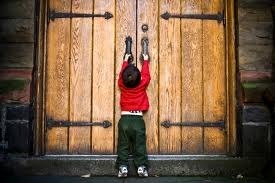

The little boy was raised, then, to question what he heard and read—even in the Bible. And eventually, that little boy stopped going to church altogether. But much of what he heard stayed with him. He held on to lines like “…the kingdom of God is within you,” or those that seem most applicable to a reporter: “seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you.”

In that sense, this entire book was probably just the act of a little boy, knocking. And he is happy to report, so much opened up—doors he hadn’t even suspected were there.

Steve Volk's Blog

- Steve Volk's profile

- 18 followers