Why Nomad?

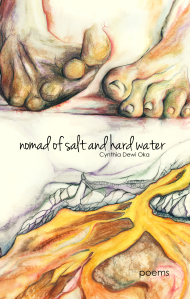

Last week, I had the blessed experience of being interviewed by Alexis Pauline Gumbs, black feminist poet/scholar/priestess extraordinaire, about my book of poems, nomad of salt and hard water. She asked me a few excellent questions – by excellent I mean, they really challenged me to ponder and search before I could articulate a response – among them, why did you decide to delve into the nomad subjectivity? - which I share here because it flowered in me long past the interview.

Initially, it might seem a straightforward enough to assume that the nomad as a controlling (convenient?) metaphor might stem from my experience as an immigrant and descendant in a long line of diasporic/displaced people, not only in North America but in Indonesia, where I was born and lived for the first 10 years of my life. But in the process of writing this book I learned that the nomad for me embodies, not necessarily a category of identity, but a particular tension between a question and a decision about how to be in the world in relation to place and the Other.

The word “nomad” originates from the Greek nomas, which means “roaming, roving, wandering,” originally used in reference to shepherding tribes that move with their flocks to find grazing pastures. So whereas the migrant infers a removal – willing or forced – of a rooted self from a homeland to a foreign space, which even if it were not hostile entails a radical adaptation, the nomad infers routes, paths, crossings that are destinations in and of themselves. The nomad does not so much root herself in place as take with her roots from wherever she finds herself momentarily residing. Further, the idea of root functions for the nomad not so much as an amplifier of authenticity, but as a means to figure out how one needs to and can reinvent oneself at any given moment. Hence why the poem “here”, ends with the definition, “an emphatic form of this: we stay within distance of a breath, self ticking into soil, organs corrupting imperceptibly like the sudden yellow of an album; before the line scatters, only this here, a part kissing time into place” (Oka, p. 65).

Who is the nomad’s Other? I think my answer to that would be whoever belongs to a place, or places. This is not an oppositional relation, however, because the metaphoric nomad of the 21st century – crossing through brilliantly diverse, bureaucratic, massive and fragmented land/oceanscapes separated by vast distances – clearly depends on the Other for orientation, reflection and at times, protection. There is a radical vulnerability inherent to the nomad I encountered while writing this book, because she is after all, a subjectivity, a spirit, invented out of necessity, rather than a member of a physical nomadic community. Speaking to a lover, she laments, “…bandaged in your bed, I found only the most fragile / of relics … / their insides wildfire as they kilned your voice / into an old tree’s remembrances of lightning, that I am here / that my just here-ness counts, and the seas / I have crossed through rain / are not my sole dwelling” (p. 21). I think it is in her relationship with the Other that the tension animating the nomad becomes most apparent. While it is her very constitution to wander, she must ask for land, the warmth of another’s flesh, in which to rest.

So back to the original question – why did I choose the nomad? I think because she is the closest articulation to what I understand the problem of emplacement and embodiment to be for people who are molding a life out of dislocation, violation, disappearance. And not only biological/material life, but a life of “holy things”. A sacred life.

AVAILABLE NOW! www.dinahpress.com.

The nomad is not dealing only with movement in and out of space. She is also negotiating her body as a space to live in and co-exist with. The body not as home, but as tent, hotel room, rented basement with the landlord living upstairs. How does one carry such a body into strange territories? How does one meet, contest or reconcile with places through that body? And how do places enter that body? Ravage it? Sustain it? I think these were the questions that concerned me most. Certainly many concrete aspects of the nomad draw on my personal experiences, but the heart of her, the thing that makes her not necessarily real, but true, is composed of braids of revelation that belong to us all. And one of the most valuable lessons I learned in the writing of this book is that the poetic craft demands us, as poets, to offer our experiences not as truth, but in pursuit of truth. One moment of this in “ode to sambal,” which describes the circumstances and physics of consuming this amazing Indonesian staple: “…our tongues swell and words forsake us / until we are leaves again scraping the blue ends / of God’s feet. for an hour or two / you hack at intestines, burning / thicker than the quiet / we have knotted into bodies” (p. 10).

I believe the nomad has an important role in our world today. A world that is contending with the deepening colonization of indigenous lands; proliferating and unending military occupations; the mass displacement of peoples due to war, famines, political and social persecution; reckless yet brutally calculated destruction of nature, habitats and human communities by the elite capitalist class; the expanding Gargantuan machines of prison, police, detention, torture, surveillance; violence and hatred perpetrated against women, children, indigenous people, people of color, workers, migrants, poor people, disabled people, queer, trans, intersexed people, and so many others whose beauty, voices, pain fall though the cracks of identity politics. And of course, the throbbing, restless life we continue to enact, defend, reach toward – as individuals/families/communities, however make-shift – in spite and because of all of this.

The nomad offers neither anthem nor solution. She offers a kind of spirit that is working at life in these times. While the poems in the book addresses various issues, one persistent area of intervention is around the idea of home. The desire to belong, to be secure (which animates so much of the global symptoms we witness and are complicit in) so easily lends itself to fear and violence, to the directive “I need” / “I am entitled to” rather than “I ask.” I am reminded of a line by Rainer Maria Rilke, “Killing is one form of our wandering sorrow…” (from Sonnets to Orpheus). And I believe the nomad, by virtue of what she is and what she needs to survive, is constantly learning to ask. To combine many roots into a roof, which she counts on rain, or will, to dissemble. Among many things, she is a renouncement of permanence. A song sturdy enough to dwell in.