Stealing and Murder in Picture Books? by Paeony Lewis

Illus by Warwick Goble, 1923I suspect you said, “No way!” But what of picture-book versions of Jack and the Beanstalk? When I was a child I felt sorry for the dead giant. That sympathy remained until I discovered the history behind the story.

Illus by Warwick Goble, 1923I suspect you said, “No way!” But what of picture-book versions of Jack and the Beanstalk? When I was a child I felt sorry for the dead giant. That sympathy remained until I discovered the history behind the story.This got me thinking about popular fairytales and I thought it would be intriguing to take a look at what we’re saying to children when we share modern versions of classic fairytales (whether as picture books or illustrated story books). So here's a peep at the history behind Jack and the Beanstalk and Goldilocks and the Three Bears.

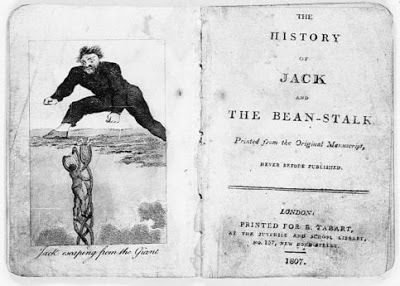

The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk, 1807At the start of the eighteenth century, Benjamin Tabart recorded his version of an oral story that had been told around the fireside for perhaps hundreds of years. In The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk, a poor boy climbs the beanstalk to recover what by rights should belong to him because the giant swindled and murdered his father (a good fairy confirms it is his destiny to avenge his father - this may have been added by Tabart to appease sensibilities).

The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk, 1807At the start of the eighteenth century, Benjamin Tabart recorded his version of an oral story that had been told around the fireside for perhaps hundreds of years. In The History of Jack and the Bean-Stalk, a poor boy climbs the beanstalk to recover what by rights should belong to him because the giant swindled and murdered his father (a good fairy confirms it is his destiny to avenge his father - this may have been added by Tabart to appease sensibilities). Illus by John Batten, from Jacob's

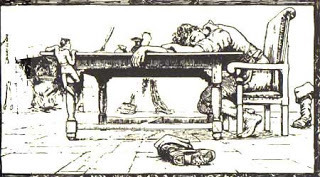

Illus by John Batten, from Jacob's Jack and the Beanstalk, English Fairy TalesOver fifty years later, Joseph Jacobs retold another version of this story, as told to him by his Australian nursemaid when he was a young boy. Jack and the Beanstalk was one of many stories Jacobs included in the popular English Fairy Tales. In this version there is no good fairy and there is no overt moral justification for the robbery of the bag of gold, the hen that lays golden eggs, or the golden harp. Jack is seen as a hero who outwits an evil giant that can smell the blood of Englishmen and wants to eat them. Thus a poor boy outwits the giant and then lives happily ever after (despite chopping down the beanstalk and thereby killing the giant, although we're only told he 'broke his crown').

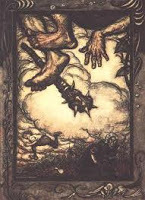

Illus by Arthur RackhamHo hum, when I was a child, this was the version I objected to. A poor boy swaps his cow for three beans, climbs the magic beanstalk, robs the giant three times, and when he’s about to be caught (and eaten!) by the giant, Jack escapes by murdering the giant, and then lives happily on his ill-gotten gains.

Illus by Arthur RackhamHo hum, when I was a child, this was the version I objected to. A poor boy swaps his cow for three beans, climbs the magic beanstalk, robs the giant three times, and when he’s about to be caught (and eaten!) by the giant, Jack escapes by murdering the giant, and then lives happily on his ill-gotten gains. However, if viewed within its original historical context, even the second version becomes more acceptable. Long ago, when told around the fire, the giant is not merely a very large, bone-crunching, blood-sniffing monster. The scary giant who lives up in the clouds in an out-of-reach castle represents somebody who is a ‘giant’ in terms of status and wealth. He’s at the top of the class system – the top of the beanstalk. Perhaps he’s a lord or a prince who has utter control of the lives of the poor who live off his land. Thus, the Jack in the story represents the canny peasants overcoming the tyrant lord and redistributing his gigantic wealth. By not naming the lord and therefore hiding his identity beneath the mask of the ‘giant’, no storytelling peasant could be punished for inciting rebellion. It was a way for the powerless poor to share and vocalise their dreams of overcoming the all-powerful feudal lord.

However, if viewed within its original historical context, even the second version becomes more acceptable. Long ago, when told around the fire, the giant is not merely a very large, bone-crunching, blood-sniffing monster. The scary giant who lives up in the clouds in an out-of-reach castle represents somebody who is a ‘giant’ in terms of status and wealth. He’s at the top of the class system – the top of the beanstalk. Perhaps he’s a lord or a prince who has utter control of the lives of the poor who live off his land. Thus, the Jack in the story represents the canny peasants overcoming the tyrant lord and redistributing his gigantic wealth. By not naming the lord and therefore hiding his identity beneath the mask of the ‘giant’, no storytelling peasant could be punished for inciting rebellion. It was a way for the powerless poor to share and vocalise their dreams of overcoming the all-powerful feudal lord.Nowadays, perhaps the ‘giant’ is a selfish dictator or huge money-obsessed corporation. However, I doubt a child would see it that way and therefore I still have a niggle about promoting robbery and murder, although I now understand why the story was first shared around the fire. Or am I in danger of being too politically correct?

From Robert Southey's The Story of the Three Bears

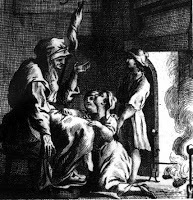

From Robert Southey's The Story of the Three Bears (note the old woman's legs!)Another fairytale favourite that has changed over time, albeit in a different way, is Goldilocks and the Three Bears. In the first half of the eighteenth century, The Story ofthe Three Bears was recorded by two different sources (Robert Southey and Eleanor Mure), and back then there was no golden-haired, cute girl. Instead, the bears were friends or brothers and the intruder was an itinerant, rude old woman who comes to a disagreeable end in Mure's story. Plus a further version existed in which the unwanted visitor was a fox (vixen). All were cautionary and threatening tales about respecting the property of others.

Illus by Margaret Evans Price, 1927Then in 1850 a little girl replaces the silver-haired old woman in the Victorian A Treasury of Pleasure Books, and shortly afterwards the bears morph into a family of father, mother and baby bear. Though it’s not until 1918 that the name Goldilocks appears in Flora Steel’s English Fairy Tales. So over time, the ominous oral tale has developed into what many see as a gentle warning to children of the perils of wandering off and the dangers lurking behind cosy facades.

Illus by Margaret Evans Price, 1927Then in 1850 a little girl replaces the silver-haired old woman in the Victorian A Treasury of Pleasure Books, and shortly afterwards the bears morph into a family of father, mother and baby bear. Though it’s not until 1918 that the name Goldilocks appears in Flora Steel’s English Fairy Tales. So over time, the ominous oral tale has developed into what many see as a gentle warning to children of the perils of wandering off and the dangers lurking behind cosy facades. Once again, as a child I was uncomfortable about Goldilocks and felt the bears has been mistreated (I must have had a strong sense of right and wrong!). Regardless of Goldilocks being a cute wee moppet, I was more in tune with the original interpretation. I don’t think I’m alone as there have been contemporary retellings that cast the bears in a positive light. In particular, one picture book, Beware of the Bears, makes me smile (a naughty smile), as in this book the vengeful bears mistakenly trash Goldilocks home!

Once again, as a child I was uncomfortable about Goldilocks and felt the bears has been mistreated (I must have had a strong sense of right and wrong!). Regardless of Goldilocks being a cute wee moppet, I was more in tune with the original interpretation. I don’t think I’m alone as there have been contemporary retellings that cast the bears in a positive light. In particular, one picture book, Beware of the Bears, makes me smile (a naughty smile), as in this book the vengeful bears mistakenly trash Goldilocks home!So what do you all think about the 'messages' in classic fairytales? Should we leave them as they are, despite social changes? Contemporary stepmothers might have a few thoughts! Or is it a case of being too politically correct, with Victorian sensibilities? And the villains do have all the best lines: Fe fi fo fum, I smell the blood of an Englishman... _______________________________________ Paeony Lewis is a children's author and writing tutor.www.paeonylewis.com

Published on December 10, 2012 00:00

No comments have been added yet.