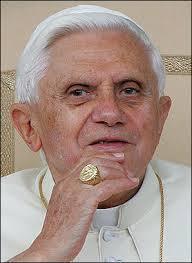

Pope Benedict brings it up again: a world political authority

“Political Authority and Universal Jurisdiction” is the topic being addressed this week by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, in a 3-day plenary session that opened today. The theme gave Pope Benedict a chance, in his address to the group, to reiterate yet again the Catholic Church’s longtime support for some form of global political authority.

“Political Authority and Universal Jurisdiction” is the topic being addressed this week by the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, in a 3-day plenary session that opened today. The theme gave Pope Benedict a chance, in his address to the group, to reiterate yet again the Catholic Church’s longtime support for some form of global political authority.

Though the Catholic News Agency article reporting the talk refers to this controversial idea as one “envisioned by two popes” (making reference to Blessed Pope John XXIII alongside Benedict himself), this is understating the case. Besides John XXIII and Benedict XVI, Blessed Pope John Paul II and Pope Paul VI also supported the idea prominently. So that’s four popes who have pushed it — every pope of the past half century, in fact (other than the one who only reigned for a month in 1978).

One reason this is especially worth pointing out is that it highlights the way that the Catholic idea of subsidiarity has been distorted and misrepresented for political ends lately. Recent vice-presidential candidate Paul Ryan, often referred to as the intellectual leader of the Republican party, made much of his Catholic faith during 2012 and cited it, and in particular the Catholic moral principle of subsidiary, in support of his economic policy proposals.

Ryan, however, presented subsidiarity as an anti-big government principle, as almost a Catholic endorsement of a “government is the problem” approach. It is “really federalism,” he said, and insisted that it supports “not having big government crowd out civic society.”

While subsidiarity certainly can and does mean that many problems should be addressed at local levels by local organizations and governments, it is far from being ”anti-big government.” Subsidiarity says social problems are best addressed and most effectively solved at the lowest level possible and at the highest level necessary. Thus it recognizes that sometimes bigger is better, too. Sometimes, in fact, bigger is essential.

That this more complete understanding of subsidiarity is the authentic (and authentically Catholic) one is made obvious by the fact that the very same popes who have been strident in their support of Catholic social teaching (which includes subsidiarity as an important aspect) and made many strong contributions to its dissemination and development have also been vocal supporters of the development of some form of world political authority.

Their thinking has been that in modern society, which is marked by so many elements that are absolutely global in scope, there will always be some issues that a global political authority can address most effectively. (It was just over a year ago, for example, that the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace called for some form of global financial authority to adequately address the circumstances created by today’s global financial markets.)

This is precisely the point that Pope John XXIII made in his 1963 encyclical letter, Pacem in Terris. If subsidiarity were fundamentally opposed to “big government,” what sense would it make for this pope — who produced two landmark soclal encyclicals during a 4-and-a-half-year pontificate — to write (in section 137):

This is precisely the point that Pope John XXIII made in his 1963 encyclical letter, Pacem in Terris. If subsidiarity were fundamentally opposed to “big government,” what sense would it make for this pope — who produced two landmark soclal encyclicals during a 4-and-a-half-year pontificate — to write (in section 137):

“Today the universal common good presents us with problems which are world-wide in their dimensions; problems, therefore, which cannot be solved except by a public authority with power, organization and means co-extensive with these problems, and with a world-wide sphere of activity. Consequently the moral order itself demands the establishment of some such general form of public authority.”

Here, in fact, Good Pope John supported this broader form of government idea specifically in terms of subsidiarity. Pope Paul VI repeated the idea in his 1967 encyclical Populorum Progressio (section 78). Pope John Paul II did it in his Message for the World Day of Peace in 2003. And Pope Benedict XVI did it in his 2009 encyclical Caritas in Veritate (section 67).

(Note that in every case but one here, the teaching is offered not in a relatively obscure Wednesday audience address or homily at Sunday Mass, but in the context of a papal encyclical. When an idea shows up in one of those, it doesn’t get there by accident.)

So it’s not surprising that Pope Benedict once again today put papal support behind the idea.