Thirteen ‘Twelve

Unfortunately we obediently deposited our camera with the guards at the entrance of the CCP so we weren’t able to take any photos of the works. I think that CCP should allow cameras inside, especially in exhibits of contemporary works, which we all know are difficult to document. All photos here courtesy of Style RPA.

I appreciate how the curator of the 2012 Thirteen Artists exhibit tried to make the show, as well as the works of the individual artists, as accessible to the public as possible. This is achieved by including wall notes that sometimes explain not only the exhibited works, but also each awardee’s background & artistic preoccupations. Exhibited as well are the artists’ studies & proposals, shedding light on their working process. By the entrance to the gallery is a TV monitor where the audience can view a documentary of the artists briefly answering the question: “Why do you make art?” I love how the show makes every effort to reach out to the audience &, with all the flak that CCP has been receiving since last year’s Kulo hullaballoo, seemingly try to justify the existence of the Thirteen Artists institution itself.

I like Walking Suitcases by Marina Cruz because of its simplicity & cohesion. Various objects are collected into photographed sets contained in resin suitcases, helping the viewer figure out a narrative, or write her own, by compartmentalizing the memories that are put in place. The found balustrades that serve as the suitcases’ feet also call to mind old houses, strengthening the idea of family histories. The wooden literal feet that design the balustrades & the green color of the suitcases suggest movement & life to an otherwise static installation.

I also like Riel Hilario’s woodworks. The title, What is essential is invisible, is a reference to the classic children’s story that complements the artist’s recollection of wanting to fly as a child. The title also gives the work a religious sense that is first made felt by the fact that the wood used is the same as that from which santos are carved.

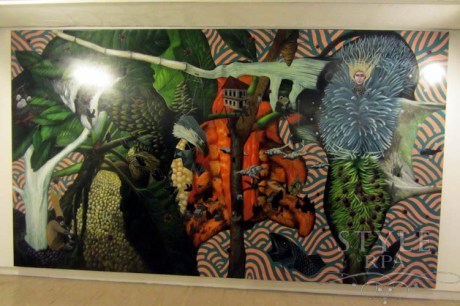

Rodel Tapaya’s painting is like a contemporary epic, or a long-winding riddle. It’s composed of fantastic images like giant birds, Miyazaki-like flying ghosts, suspended diorama-sized houses, &c. These images of different proportions meld with each other, & following each of their movements with the eye is an engaging exercise. The blank space on the adjacent wall makes me wonder, though, if there are supposed to be two paintings, as indicated in the artist’s studies. It would have been an interesting diptych. The narrative or narratives from the universe that Tapaya created could easily extend onto another painting (& a third & a fourth).

I feel that Michael Muñoz’s work is heavy with references, making it difficult to appreciate. Entering the alcove in which the work is installed is like entering a sacrificial room. Kandila & Gregorian chant na lang ang kulang. I feel that there is a continuity of meaning—from the graffiti work of a hooded man on one wall to the indigenous white cloth on the table at the center to the Western, classical religious painting on the parallel wall—that is somehow disrupted, if not lost (or lost on me, at least).

Mark Salvatus’ installation is a pretty straightforward commentary on the frustrations of urban habitation. The block of hollow blocks is as claustrophobic as the looped audio recording on the amenities of urban residences for sale or for rent that issues from it.

The show is teeming with sound, by the way. Kiri Dalena’s work is pure sound—a recording of a storm’s howling wind, playing in the building’s elevator. Would it have been more powerful if the howl—or the roar, depending on how you hear it—could be heard in the whole building? Joey Cobcobo’s printwork of, if I remember right, Jesus Christ on handmade paper is accompanied by a recording of one of our “modern prophets,” those you see standing on the sidewalk or getting on the bus, preaching about how our wayward ways bring us closer to the end of the world. There’s Salvatus’ recording, & also the sounds of the various video clips on war, I think, along with a grand underscore, that make up Renan Ortiz’ Ode to Empire.

& then there’s Kaloy Olavides’ video installation of eight TV monitors that flash different signs using various instruments: the sign language, the Morse code, guitar strums. The work has something to do with decoding art. The message, as I understand it, is simple: If you can’t read signs, if you don’t know the language, you can’t call for help nor respond to one! But it could also mean the opposite: That reading art without knowing the language is ideal. That’s one way, anyway, of knowing if any work has succeeded or not.

Olavides’ installation includes a copy of Sue Grafton’s S is for Silence. It’s a clever reference to detective fiction, which does deal a lot with codes: A knowledge of cryptography has helped Sherlock Holmes solve the case of the dancing men. The book is part of Grafton’s alphabet series, in which each letter of the alphabet stands for a particular criminal case (yes, H is for Homicide). Not knowing the actual message that the whole installation spells out, I as a viewer make do with just experiencing the work visually.

I’ve lost a lot of the meaning, I can imagine! But let’s just hope that’s the point.

Faye Cura's Blog

- Faye Cura's profile

- 5 followers