Everything’s Not Alright in the Suburbs…Again.

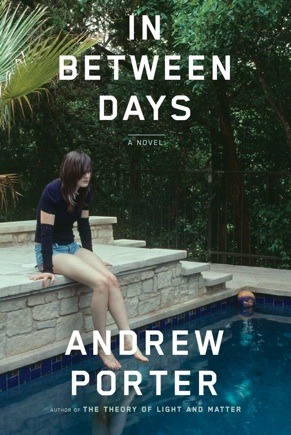

In Between Days by Andrew Porter

I remember this one lit theory course I took in grad school in which someone once argued that John Cheever had established the private-and-more-than-likely-self-induced-problems-of-middle-class-white-Americans-living-in-the-burbs trope as its own sort of fiction subgenre. I’m not sure if this is true or not, if Cheever was ultimately responsible for this, but I think we can all agree that this subgenre does indeed exist and that a lot of writers, both excellent and terrible, have gotten a lot of economy out of it. That’s not to say that this is altogether “bad” territory; it is, after all, the wheelhouse of folks like Phillip Roth and Tom Perrotta. But for a lot of lesser writers, this seems to be a kind of go-to motif, a comfort zone that, because most of their readership would likely live in these placid little worlds, aren’t worth stepping out of.

I remember this one lit theory course I took in grad school in which someone once argued that John Cheever had established the private-and-more-than-likely-self-induced-problems-of-middle-class-white-Americans-living-in-the-burbs trope as its own sort of fiction subgenre. I’m not sure if this is true or not, if Cheever was ultimately responsible for this, but I think we can all agree that this subgenre does indeed exist and that a lot of writers, both excellent and terrible, have gotten a lot of economy out of it. That’s not to say that this is altogether “bad” territory; it is, after all, the wheelhouse of folks like Phillip Roth and Tom Perrotta. But for a lot of lesser writers, this seems to be a kind of go-to motif, a comfort zone that, because most of their readership would likely live in these placid little worlds, aren’t worth stepping out of.

Now, I am reticent to lump Andrew Porter’s In Between Days into this category: I truly did enjoy reading it. Porter’s prose is crisp and controlled, and his devotion to his characters, to giving them each their own unique presence, is admirable if not a little heavy-handed. But these aren’t exactly mold-breaking characters. In a lot of ways, they are dangerously familiar. There’s Elson, a forty-something architect who, having separated from his wife, is now involved in a dubious relationship with a much younger woman. His wife Cadence has also sought out new mates, though we get the sense that, like Elson, these are mostly time-killers, ways of filling some kind of void. Richard, their son, spends his days waiting tables and his nights at ad hoc poetry workshops led by a professor at Rice whose interest in his work is questionable. And then there’s Chloe, the youngest child, who finds herself embroiled in a potentially murderous fiasco while away at college.

The real story begins when Chloe, accompanied by her boyfriend Raja–the supposed perpetrator of the crime in question–returns to Houston, where Richard arranges for the two of them to be smuggled into Mexico. Upon catching wind of their daughter’s return to town and her plans to flee, Elson and Cadence find themselves coming together in hopes of salvaging their family.

The real crux of the book, however, is the way that each character continuously gets in his/her own way, sabotaging his or her own plans, making unforgivably stupid choices. This is In Between Days’ book’s biggest problem, I think, the way it clobbers us over the head with the very notion of character fallibility. Because here’s the thing: there is no reaon for these people be so feckless other than the fact that there would be no story without it. That’s what this particular subgenre does, it reassures us that all those outwardly happy, easily mockable suburbanite families are really just as fucked-up and miserable as the rest of us. Very few–if any–of the problems this family faces are brought about by anything other than their own naivety and/or selfishness. And after a while it gets hard to sympathize.

This is not to say that the obstacles a character faces can never be self-imposed. Hell, look at Hamlet, Willy Loman, or almost anything by Poe. Self-destructive characters can be a lot of fun–when there’s a reason for them to self-destructive, that is. In the case of In Between Days, however, we seem to be reusing a well-worn Desperate Housewives-ish template that assumes characters are only as interesting as the problems they cause for themselves. The book is a good read, maybe even great in some places (the creepy professor character is particularly fun, although this may be the disgruntled MFA grad in me talking), but there is very little to take away, which is a shame because it’s clear from Porter’s prose that he’s capable of so much more.