The two-term era

When Barack Obama won re-election last week, he became the third consecutive president to win a second term. The last time that happened was at the beginning of the 19th century, when Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and James Monroe benefited from Democratic-Republican dominance at the presidential level. Indeed, by the time Monroe ran for re-election in 1820, the opposition Federalist Party had collapsed. No incumbent enjoys the same advantage in the current political environment; there will always be a well-organized, well-funded partisan foe.

Tracing the current pattern back in time a bit further, Obama is the fourth president in the last five to win re-election. Only George H.W. Bush in 1992 failed in his quest to secure a second term. Two terms has become the new normal for American presidents.

Tracing the current pattern back in time a bit further, Obama is the fourth president in the last five to win re-election. Only George H.W. Bush in 1992 failed in his quest to secure a second term. Two terms has become the new normal for American presidents.

Contrast this pattern with what preceded it: between 1960 and 1980, only Richard Nixon won reelection (and, of course, he did not manage to complete his second term). John F. Kennedy might have won in 1964 had he lived. But Lyndon Johnson decided not to seek a second term, and both Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter were defeated in their bid for re-election.

This striking reversal of fortune for sitting president calls for analysis. Several factors may be at work, but one stands out. Most recent incumbent presidents have enjoyed the advantage of early, unified support from their own party.

Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama faced no challenge when they decided to seek renomination. Certainly they had their critics within their own party, especially the Democratic incumbents. Both Clinton and Obama faced murmurings of liberal discontent. But it did not suffice to propel a challenger to enter the fray.

On the other side, George H.W. Bush encountered sharp conservative opposition from Pat Buchanan. Although Buchanan never represented a serious threat for the nomination, he did pressure Bush 41 from the right. Bush’s situation paralleled that of Johnson, Ford, and Carter, each of whom did battle with a popular rival in his own party (Eugene McCarthy, Ronald Reagan, and Ted Kennedy).

With no competition for the nomination, a sitting president does not have to engage in one of the familiar exercises of American electoral politics in the modern era — repositioning himself between the primary season and the general election campaign. Mitt Romney’s attempt to redefine himself in the final months of the campaign, to shake the “etch-a-sketch” once he sewed up the nomination, is a necessary move given the sharp difference between the primary and general electorates.

Dedicated Republican voters today skew far to the right of the population as a whole. This gives a boost to idiosyncratic ideologues (libertarian Ron Paul) or fire-breathing social conservatives (Rick Santorum), who stand no chance of winning in a general election. The make-up of the Republican primary electorate, weighted heavily toward (or, more accurately, weighed down by) Tea Party activists, also forces more moderate or malleable candidates to market themselves as, in Romney’s words, “severely conservative.”

Much the same situation applies in the Democratic Party, with the activists and party-linked interests tilted well to the left. In 2008, Democratic aspirants for the presidential nomination elbowed each other aside in their eagerness to call for the quickest end to the war in Iraq or the most comprehensive version of universal health insurance. Fortunately for the Democrats, their primary electorate makes its peace more readily with the need to line up behind a relatively moderate candidate who can win a general election. Nevertheless, the leftward tug can leave a Democratic nominee with some baggage entering the general campaign.

To secure a nomination by acclamation, as most recent incumbent presidents have done, confers an extraordinary advantage on a candidate. He has the luxury of positioning himself in the political center from the outset. He does not face accusations that he is feckless and unprincipled. He need not worry that any position he takes will alienate either those in his party who supported him during the primaries or middle-of-the-road voters. In an evenly split polity, where campaigns vie for the finicky affections of the independents between the two camps, the incumbent president begins with an important head start.

If this pattern holds in the future, the stakes rise in the next presidential election. With no incumbent on the ballot, we will not be choosing a president for four years, but very likely for eight.

Andrew Polsky is Professor of Political Science at Hunter College and the CUNY Graduate Center. A former editor of the journal Polity, his most recent book is Elusive Victories: The American Presidency at War. ReadAndrew Polsky’s previous blog posts.

Subscribe to the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only law and politics articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

Subscribe to only American history articles on the OUPblog via email or RSS.

View more about this book on the

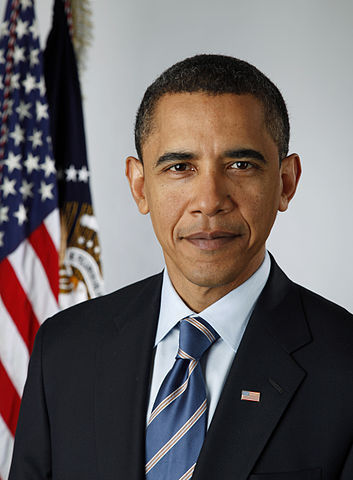

Image credit: Official photographic portrait of US President Barack Obama. US government photo.

Oxford University Press's Blog

- Oxford University Press's profile

- 238 followers