Character References: Part Four

So it continues: the second lag of The Rainbow characters and the fourth character reference post overall. Good god. I’m realizing now just how much of my computer is photos of actors/musicians/random models because they just sort-of-almost-kind-of look like one of my characters. I barely even have any photos of myself, but I have so many of characters.

Lydia

As you can see, she is clearly based around Erykah Badu. In the original edition of the story, I even had her name as Erykah for such a long time, then changed it to Lydia because it didn’t feel right at the end. This is how I imagine Lydia, Jasmine’s midwife and political activist/group leader. She is tall, thin, and speaks very deliberately (like Cassandra, she rarely uses contractions). She’s a character that has been with me since the beginning when I first realized in 2008 that I wanted to write this story again. I envisioned her as a black woman from the beginning and this distinction is something that I want to spend more time on.

While it can be easier to represent diversity in media (since it is the body that is on display there), I don’t know if the same can be said for books. Since we read from our own subject positions (and also write from them), we have a tendency to interpret others how we envision ourselves. If race is taken into consideration, this leads to a lot of different interpretations of what a character may look like, unless it is specifically stated in some way. Dominant forms of representation are almost always assumed until otherwise mentioned. I’m thinking specifically of the controversy surrounding Rue in Hunger Games; my boss at the time was ranting about how people didn’t realize she was black until the movie came out, even though it was stated in the book several times. I became aware of this fact with my own writing around the time that I was beginning this book again, and I realized that, aside from sexuality and gender, there was not much diversity at all in my characters. This can happen a lot with fiction or fan-fiction that’s not already minority focused. It’s not explicit racism or an act of deliberate exclusion; it just happens sometimes because of the way the culture already produces media.

Toni Morrison has a really good book about this, where she discusses how creative writing especially can reflect the biases of the author (Playing in the Dark, 1992). Furthermore, the biases of the author are a further reflection of the culture that the author is living in. As soon as this was articulated to me, I began to see evidence of it. At the time, I was in a lot of Women’s Studies classes and reading works by Audre Lorde, bell hooks, and Morrison and it was shaping how I was thinking about things. To a certain degree, university changes the culture that you live in, and so my imagination changed. Lydia and Hilda are some of the many different characters who cropped up and are probably the best examples of this.

I know that calling the book The Rainbow can very easily play into the gay community it’s associated with or to diversity as a whole, but those readings of it have always seemed to hokey and benign to me. Identity politics is, I suppose, the more “academic” way of looking at diversity and most of my undergraduate and graduate time has been spent dealing with identity politics. I feel more comfortable associating some of the story’s goals of representation at including a more diverse field of identity politics, but it’s something that I also just don’t accept unquestioningly. Identity politics are not perfect, and Thomas himself struggles with this especially when applied to queer narratives. He has many confrontations with Lydia and Hilda, in the next chapter and in this section. Identity politics are good for helping to find out who you are and to get a sense of structure to yourself – but as Lydia stresses, it is about a community effort as well. We all have to work together in order to make sure that the other person next to us isn’t feeling left out or offended. It takes talking to people, different people, and to try to inhabit what their life has been like in order to gain a better understanding. But anyway, here are some photos.

Hilda

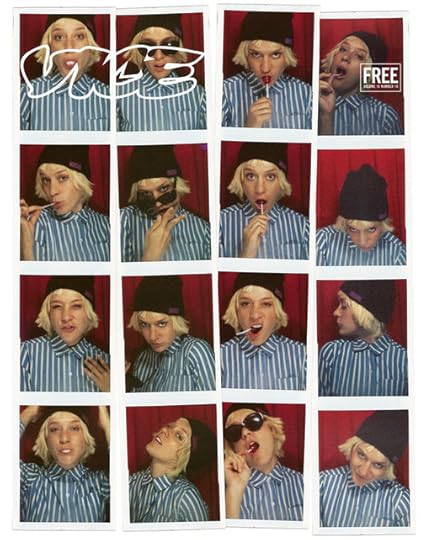

For the most part, Hilda looks like Chloe Sevigny. But this is only half of it.

She has a distinctive facial structure, blondish hair, and the same type of style and dress (playful, queer, and mutable). But she is clearly missing one thing that Hilda does have: fat. Hilda is a larger character. She’s not obese or even really overweight, really. In the story she is pregnant (surrogate, yet another reason why she’s an important character), but it’s not her pregnancy that’s making me view her in my imagination as a larger woman. It’s just how she came to me, but it was something that really stood out as I tried to find a photo that conveyed this physical difference.

A lot of the women in the story, I realize now as well, tend to be on the thinner side. Vivian and Alexa aren’t, but that’s because they’re older (metabolism slows) and have had children. I’m not going to make things too serious with how I’ve bought into ‘ideals of beauty’ or how I’ve internalized the oppression of the strict culture of thinness with my female characters, because I don’t think that’s quite right. But there is something interesting here to think about, that’s been said in a million other feminist texts, about how we envision people before we see them.

Anyway, enough seriousness. I think my initial idea to name the character Hilda (because I wanted someone who had similar origins to Jasmine – so Scandinavian or Norwegian) had struck some old childhood memory as well, because the other person who resembles her character (in physical size and some facial features, too) is Caroline Rhea.

Basically, if Chloe had Caroline’s body and maybe some of her more cheerful features, that would be Hilda. And I really like her. The above image sort of reminds me of how Jasmine and Hilda would look relational to one another. Although Hilda is older than Jasmine, she’s definitely not as old as Caroline Rhea, so that’s something to keep in mind, too.

As much as she adds to the representation in the story of diversity and whatnot, she encounters a lot of problems. In Women’s Studies and Cultural Studies, there is usually a divergent branch of theory called Queer Theory. The name seems like a huge misnomer, because in this theory, two heterosexual people can be queer. Queer doesn’t translate into same-sex action, but to subversive, different, and against the mainstream. Two heterosexual people can be queer if they engage in BDSM or are in an open relationship. If they diverge from that white picket fence mentality, basically. On the other hand, if two gay men get married in a very typical ceremony, they are more ‘straight’ than anything. The dichotomy in this brand of theory becomes queer/straight or queer/normal and it is utterly bad to be normal.

The resistance that Thomas has towards Hilda at first is because she is very queer and embodies a lot of the theories. She is hosting sex workshops, she is talking about fisting, she is basically outrageous. This could be argued as a bit of a caricature but trust me. Most of her dialogue is taken from people I’ve encountered studying what I’ve studied. People have called me “queer” a lot and I’ve never really liked it, like Thomas, because it just didn’t feel right. It feels as if they remove the humanity – the love for the sake of love, not for the sake of it being weird or different – away. The tension between Thomas and Hilda is the tension between two different ways of expressing same sex desire. Hilda and Jasmine’s relationship is there to contrast and display the complex nature behind behind same sex desire. It really isn’t as simple as liking men or women – there are the ways you love someone and the ways in which you think about loving them, too.

There is also a certain tension between private and public. Hilda represents that public side of desire, the declaration, the pride parades and workshops. Thomas is private. He fell in love in secrecy and his first serious relationship had to happen indoors. As much as he wants to go outside with Bernard and have a good life with him, he doesn’t feel the need to declare it. Love for him has always happened behind closed doors, and just because you don’t announce it everywhere you go and don’t come out to every single person you meet does not mean you are ashamed or afraid. It’s simply another way.

I tend to resist a lot of the “coming out” narratives now that crop up within books or even in real life. As Bernard has said before in January, the onus is not on the perverts to come out and be wonderfully accepted as “okay.” The onus is on the society to change so the coming out isn’t even needed.

I think I may probably end up writing an entry, similar to Essays on Art, and list a lot of books and materials that have been helpful to talk of these distinctions, especially since I just rambled in a post that was supposed to be for character pictures. Soon, maybe.

Evelyn Deshane's Blog

- Evelyn Deshane's profile

- 46 followers