Is an Embryo Like a Bean?

The New Yorker‘s Adam Gopnik, critiquing the metaphysics of a nickname used by Paul Ryan in talking about human life:

The New Yorker‘s Adam Gopnik, critiquing the metaphysics of a nickname used by Paul Ryan in talking about human life:

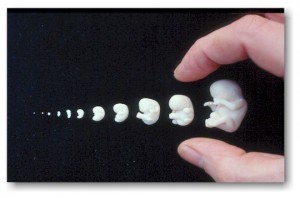

Ryan then went on to say something oddly disarming in its inherent lack of self-awareness. He talked about how, looking at a first sonogram of his daughter, he was thrilled by the beating heart in the tiny “bean” on the image, so much that he and his wife still call that child “Bean.”

As someone who is not often accused of being indifferent to the joys of fatherhood, I recognize the moment—and in fact still have that same early ultrasound picture, two of them. But Ryan’s moral intuition that something was indeed wonderful here was undercut, tellingly, by a failure to recognize accurately what that wonderful thing was, even as he named it: a bean is exactly what the photograph shows—a seed, a potential, a thing that might yet grow into something greater, just as a seed has the potential to become a tree. A bean is not a baby.

Ross Douthat responds with a model of how to cut through bad logic:

Gopnik is taking the congressman’s nickname for his unborn child and literalizing it—not, as he thinks, in the service of delivering some hard facts about the nature of life in utero, but in the service of obscuring those facts in the service of the pro-choice cause. On the one hand, calling an embryo a “bean” makes embryonic human life sound like a form of vegetative life — not an uncommon rhetorical move in these debates, but also one that collapses on the barest scrutiny. A bean is not remotely like a baby, certainly, but neither is a baby remotely like a full-grown bean plant, and that difference has a more obvious bearing on the debate over embryonic and fetal rights than the facile comparison between plant embryos and human ones. Outside of the world of level five veganism, neither the bean nor the plant have a strong moral claim on us, and it’s their essence as vegetables, rather than their level of development, that makes all the moral difference. Not even the most ardent enthusiast for the idea that ontology-recapitulates-phylogeny has ever argued that developing human life passes through a vegetablephase on its path toward full adulthood. Biologically speaking, we begin as we end up — which is one reason why any normal person would be rightly horrified to find the beans switched out for human embryos in their favorite cassoulet.

What’s more, even as a more indirect analogy the “bean” line is misleading, because it invites the reader to imagine the embryo in a kind of stasis — like a kidney bean in your cupboard or an acorn on the ground, awaiting favorable conditions to actually crack its shell and grow. It’s an image that evokes the old folk wisdom about “quickening,” which informed English common law on abortion in days before we knew much about what actually happens inside the womb. But if there’s anything that ultrasound technology has demonstrated beyond a shadow of a doubt, it’s that an embryo is “quick” long before the mother feels its movements. What Ryan saw on in the ultrasound photo is rather obviously a growing life—a shoot or a sapling, if you insist on pushing the tree analogy further, which doesn’t just have the “potential” to “grow into something greater.” No less than a newborn or a teenager, albeit at a much earlier stage, it is already in the process of growing into full maturity, and that process will necessarily continue unless someone intervenes to put a stop to it.

The rest of Gopnik’s piece offers a variation on the conventional pro-choice argument about the impossibility of knowing when a human life is finally “fully grown and when it isn’t”—or phrased more philosophically, when “the formed consciousness that distinguishes human life from bean life arises”—and why this uncertainty requires us to err on the side of (his words, not mine) “every woman for herself.” The broader argument-from-uncertainty is less implausible than the direct comparison of embryo to an acorn, but for a supposed champion of enlightenment the combination is still a strange one. In the name of science and progress, Gopnik is offering dubious embryology plus a view of human rights that’s essentially mysterian—abstracted from biological identity, agnostic about its own parameters, more comfortable evoking folk wisdom than reckoning with the science that’s replaced it. He’s draping himself the mantle of secular reason even as he talks misleadingly about biology and declares that some of the most crucial questions about justice, the law and human rights are eternally inaccessible to reason.

You can read the whole post here, which also gets into issues of the relationship between church and state, belief and policy.

Justin Taylor's Blog

- Justin Taylor's profile

- 44 followers