Mountains, the sublime, and where the heck I’ve been lately

So . . . I meant to take a week or so off. I meant, in fact, to post that I meant to take a week or so off. But it didn’t happen that way.

Sorry?

But hey! I’m back, and I’m finally finishing a post I started ages ago.

You see, part of my disappearing act involved a trip to the New Mexico and Colorado mountains. I’m from North Texas, and a summer trip to New Mexico and/or Colorado is practically required. We live in a very flat, very hot land, and there comes a point every summer where if you don’t get away you will have a meltdown in the driveway, by which I mean you will literally melt in your own driveway. The only cool locations within driving distance are Northern New Mexico and Southern Colorado, so everyone packs up the car, has breakfast in Wichita Falls and lunch in Amarillo, and fetches up in Santa Fe about dinner time.

View from Wolf Creek Pass near Pagosa Springs, Eric Voss. Members of my family have been taking variations of this photo for more than 60 years. I found this one online, thus proving other people also find this view irresistible.

This tradition is generations old. In lucky families, an earlier generation invested in a cabin. (No one in my family apparently had that sort of forethought, or perhaps capital.) The result is that Texas families have “their” mountains. Families have “always” gone to Red River, or Eagle’s Nest, or Raton. They go back every year or every few years and develop traditions. It becomes essential that they eat at certain restaurants, visit certain national parks, shop at certain gift shops.

In my family, our mountains are those surrounding Pagosa Springs in southern Colorado. My mom went there as a kid, and my husband and I took our honeymoon there. And this year, for the first time in ages, we got to go back.

It was fantastic. Our first day in Pagosa Springs, we drove out to the National Park and found “our” stream, a rushing mountain rivulet with an island in the middle. As long as I can remember, the mission has been to cross the stream and get on the island. The difficulty of the task changes every time based on the locations of rocks and fallen trees–this time it was a snap, but other years it’s been hair-raising. The first year I took my husband there, he asked “Now why are we crossing this stream?” and I honestly didn’t have a good answer other than that that’s what you do. It was proof that I married the right guy that he accepted this without question and entered into the stream-crossing enterprise with vigor.

My husband in the middle of "our" stream. Yes, he did in fact have a heck of time getting back to dry land.

Once we got onto the mystical island, there’s a spot you can sit with a waterfall in the foreground and towering mountains in the background and rushing water on either side. It’s magnificent. Everything’s pounding and roaring and soaring and it all leaves you breathless.

What does this have to do with art or culture? Well, the sense that I got sitting on that stream is surprisingly historical. It’s not universal but rather cultural.

Prior to the mid-18th century, most people had no appreciation for mountains at all. English writers and artists in particular found mountains nothing more than annoyances, hindrances to agriculture and a barriers to travel. Mountains were described in English literature as barren protuberances, insolent and inhospitable; as blisters, tumors or warts.

To some degree, these attitudes were borrowed by English writers from Roman writings; the Romans seemed to see mountains as inconveniences. For other English writers–particularly earlier ones–the negative view of mountains was largely based on ignorance. Shakespeare, for example, almost never mentions mountains, but then he probably never saw one. England is hilly but not mountainous, and he never ventured to more rugged portions of Wales and Scotland.

By the 17th century, however, many English writers had traveled and seen mountains. And they weren’t impressed. Andrew Marvell called mountains hook-shouldered and unjust, excrescences (love that word) that deform the earth and frighten the heavens.

This attitude started to shift in the 18th century, and by the 19th mountains were a favorite subject for poets and artists alike. So what changed?

What changed was Romanticism, which was more than a poetic movement. Romanticism was a whole worldview that, among other things, saw nature (Romantics would say Nature) as a source of inspiration and wisdom. Critical to all this was the concept of “the sublime,” which describes something vast, mysterious, awesome, terrifying yet wonderful. In other words, mountains.

In a space of a hundred or so years, people went from being annoyed by mountains to near worshipping them. Instead of being inconvenienced by the Alps, which made travel from France to Italy so difficult, people came and marveled at them. Mary Shelley, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron spent a summer near Geneva and went around appreciating the mountains like mad (when they weren’t telling each other ghost stories.) These were the same mountains that Voltaire lived amongst for 20 years and hardly noticed at all. (In his Philosophical Dictionary, the best thing Voltaire could say about mountains is that they were the source of streams and rivers that nourished life in the valleys.)

Wordsworth could hardly see a hill without swooning. Even the sober Jane Austen caught the fever, or at least conveyed it to her heroine Elizabeth Bennet. When Lizzy is invited to tour the Lake District with her aunt and uncle, it evokes a reaction twenty times more effusive even Mr. Darcy’s proposal of marriage:

“Oh, my dear, dear aunt,” she rapturously cried, “what delight! what felicity! You give me fresh life and vigour. Adieu to disappointment and spleen. What are young men to rocks and mountains? Oh! what hours of transport we shall spend! And when we do return, it shall not be like other travellers, without being able to give one accurate idea of anything. We will know where we have gone—we will recollect what we have seen. Lakes, mountains, and rivers shall not be jumbled together in our imaginations; nor when we attempt to describe any particular scene, will we begin quarreling about its relative situation. Let our first effusions be less insupportable than those of the generality of travellers.”

Notice that Lizzy is at pains to explain they will properly appreciate the landscape,unlike the “generality of travellers.” It was felt that most poor souls lacked the refinement to truly grasp the sublime.

Philosophers dwelt at length on the sublime, particularly German philosophers including Kant, Schopenhauer and Hegel. And artists started painting mountains in new ways.

Mountains had appeared in art all along, although usually in the background. Leonardo da Vinci created marvelously mysterious mountains:

Leonardo da Vinci, Detail from "The Virgin of the Rocks" (London version), 1498-1508

But with Romanticism, landscapes became increasingly important–and increasingly dramatic. Previous artists painted domestic scenes of land tamed by agriculture; Romantic artists painted wild, wondrous landscapes of mountains soaring–even erupting:

[image error]

J.M.W. Turner, "The Eruption of the Soufriere Mountains in the Island of St. Vincent, 30th April 1812," 1812

Gerhard von Kügelgen, "Portrait of Caspar David Friedrich," ca. 1810–20

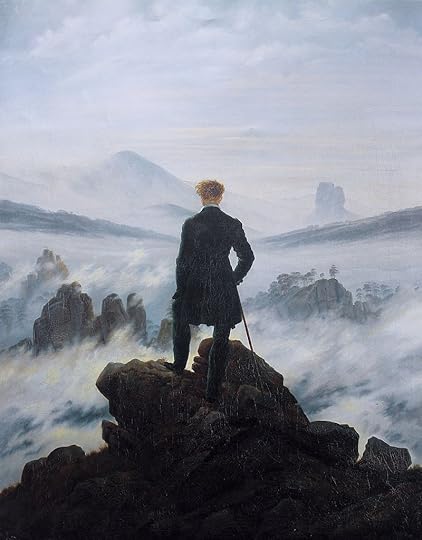

The ultimate Romantic artist was undoubtedly Caspar David Friedrich. (It’s not clear if he really had such a piercing gaze or simply liked to think he did.) Friedrich is all about the subline. He routinely paints dramatic landscapes of mountains, oceans or barren hillsides. Sometimes ancient ruins haunt the scene–the Romantics adored ruins, particularly Gothic ones. (The contemporary idea of being Goth–that is, dark, emo, moody–can be traced directly to the Romantic love of all things Gothic–or Gothick, as the novelists spelled it. Jane Austen would have understood Gothic to mean old, creepy, mysterious, emotional, and dark.)

Against the landscape, one or two human figures stand in contemplation, dwarfed by the scene before them. They are caught in appreciation of the sublime.

Caspar David Friedrich, "Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog," 1817

This is a vast subject, and I’ve only touched on it. American artists, for example, deserve their own discussion of how they painted the landscape of the West. If you’re curious, there’s a classic text on the Romantic discovery of mountains called Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory by Marjorie Hope Nicolson from back in 1959; you can read a large portion of the text online.

The temperatures are falling to reasonable levels here in Texas, and we won’t go back to the mountains until next year. It’s lovely to see traditions continue; my son now has “his” mountains outside of Jemez Springs in Northern New Mexico, where we’ve stayed the last several years with family.

But remember the next time a landscape makes you catch your breath and you stand still in wonder: Voltaire would have walked on by. Thank you, Romantics, for giving us the mountains.