Meeting Hawaii’s Next Generation Authors? (…and How I Handle Criticism)

A young man sitting in the back row tentatively raised his hand. I was talking to a group of history students and their teachers at Kamehameha School last week about my book, Lost Kingdom: Hawaii’s Last Queen, the Sugar Kings, and America’s First Imperial Adventure, published by Atlantic Monthly Press earlier this year. “How do you deal with criticism as an author?” he asked.

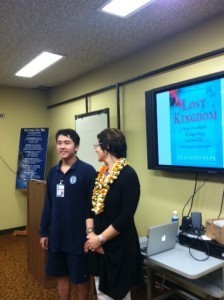

Meeting with Hawaiian language immersion students at Ke Kula Kaiapuni o Anuenue

That was a very good question. Lost Kingdom has gotten good reviews in the New York Times Sunday Book Review, the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and elsewhere. There are 57 reader reviews on Amazon and the vast majority of the reviewers gave it four or five stars.

But one reviewer – the author of a book on hula who is herself from the mainland – criticized it in her Amazon reader review on many levels, suggesting that an outsider couldn’t possibly write a sensitive or intelligent book about the islands. Other Hawaiian scholars have criticized me for not having used more Hawaiian-language source materials. Their basic argument is that someone who can’t read the Hawaiian language newspapers of the 19th century can’t write a thorough history of the kingdom.

So how do I handle criticism? In answering the student that day, I started off by joking that after nearly three decades as a reporter, writing for the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, and BusinessWeek magazine, my skin had grown pretty thick and that helped me separate professional criticism from my personal feelings. I also told him that I care very deeply about getting things right. That’s one of the reasons why I’ve enlisted the help of scholars and friends to help me make corrections for the paperback version of Lost Kingdom, which will be out at the end of the year.

That was one of the first lessons I learned as a new fact-checker at the American Lawyer magazine, straight out of college. If there’s a mistake, own up to it and make sure it gets fixed. The story and both your and the publication’s reputation are more important than a dented ego. In terms of Hawaiian cultural values, the goal is to be pono – which, roughly translated, means do the right thing. That’s why I’m taking so much care in correcting and updating the new edition of the book. Most of the changes are very small, but it’s important to make them.

Later that same da y, I got an earful from a University of Hawai’i scholar at an event at the Bishop Museum. She pointed out things she didn’t like about it – ranging from my description of a Hawaiian laborer in a sugar mill (she thought I had sexualized him) to her contention that human sacrifices were never made to the goddess Pele. I’m checking out what she said and will fix what’s wrong. But I think she didn’t understand that my goal was never to write an academic history: my goal was to write a book for people who knew little to nothing about the history of the Hawaiian islands. And the reason I included more than 800 endnotes, documenting my source materials, was that so that others could come along and build on my work – telling the story from their own perspectives.

y, I got an earful from a University of Hawai’i scholar at an event at the Bishop Museum. She pointed out things she didn’t like about it – ranging from my description of a Hawaiian laborer in a sugar mill (she thought I had sexualized him) to her contention that human sacrifices were never made to the goddess Pele. I’m checking out what she said and will fix what’s wrong. But I think she didn’t understand that my goal was never to write an academic history: my goal was to write a book for people who knew little to nothing about the history of the Hawaiian islands. And the reason I included more than 800 endnotes, documenting my source materials, was that so that others could come along and build on my work – telling the story from their own perspectives.

Maybe some of the students I spoke to last week might some day write their own histories of Hawaii. And because of efforts such as Awaiaulu Project, led by University of Hawaii Professor Puakea Nogelmeier, they’ll have more source materials to work with through the Hawaiian language newspapers now being translated.

I felt lucky to be able to have so many interesting conversations last week. I was visiting Kamehameha Schools as part of a community dialogue set up by Jamie Conway, founder of the Distinctive Women inHawaiian History program, a wonderful event which took place on Saturday, September 15th, at Mission Memorial Auditorium in downtown Honolulu. I am very grateful to Jamie for arranging what turned out to be a truly unforgettable series of events, taking me places that I’d otherwise probably never have gone on my own.

Nalei Akina of the Lunalilo Home, author Julia Flynn Siler, and Jamie Conway of Distinctive Women in Hawaiian History

I went to the Lunalilo Home, the Bishop Museum (in conversation with “Uncle Ish” Ishmael Stanger, who has a new book out about Hula Kumu (hula teachers,) Kapi’olani Community College, and, most memorably, 150 students and teachers from the Kula Kaiapuni ‘o Ānuenue, a Hawaiian Language Immersion School in Honolulu’s Palolo Valley. These were all volunteer efforts on my part—my small attempt to give back to the community.

Have I planted any seeds? Might any of those kids think more seriously about becoming a writer or a historian, so they can tell stories from their own perspectives, using the newspapers that only now are being translated into English? I do hope so. As I learned from the kids at the immersion school, a key value in Hawaiian culture is Ke Kuleana (to take responsibility.) That’s what I’m doing by making corrections to the new version of my book. Mahalo to all the teachers who are helping me with this task – and also to the teachers such as Thelma Kan, who invited me to join her at dawn for a Hiuwai Ceremony on Sunday morning.

Here’s the chant that Thelma led us in, by Edith Kanakaole

E Ho Mai

E ho mai ka ike mai luna mai e

O na mea huna no’eau o na mele e

E ho mai, e ho mai, e ho mai e

Give forth knowledge from above

Every little bit of wisdom contained in song

Give forth, give forth, do give forth