A round-up, a recap, a review, another reading, and a random search term

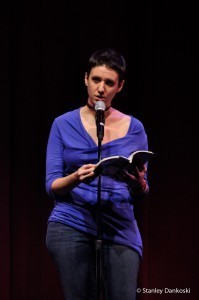

Photo credit: Stanley Dankoski

First, the recap.

Last Wednesday, I had the pleasure of reading at Literary Death Match. I should start by mentioning that my introduction to LDM was through Karyn Polewaczyk. It was October, 2010, and Karyn had just read at Literary Firsts. She e-mailed Adrian Todd Zuniga, host of LDM, and said, “You and Carissa should probably know each other.” So I tried to make the next Boston LDM. It was sold out. I tried to make the one after that–something came up. My schedule stood in the way of every single reading that came to Boston, including one wherein I knew several people reading.

NOTE: The implicit message here is that I am not only busy, but also a bad friend.

So, finally, when my schedule is at its most insane, but when everything on my plate has to do with promoting one book or writing another, I get an e-mail from Kirsten Sims, Boston LDM producer, asking if I’d like to read.

So I read. And it was an incredibly good time. Every photo on the LDM site that doesn’t depict me reading shows me laughing (and subsequently, those photos should be destroyed). But honestly, Literary Death Match is a great series because it doesn’t take itself (or its readers) so seriously. Next time it’s in a city near you, just go. Regardless of what else you’re doing. Go.

That said, just in case you missed last week’s Literary Death Match and now you’re sad because I just told you what a good time it was, you have another chance to hear me read (this time, alongside Randolph Pfaff and Lesley Mahoney). Tomorrow night, I’ll be at the Hallway Gallery in JP and I’ll be reading my short story, “1964, Berkeley,” which appeared in Consequence earlier this year and is the second section of a three-part story (the beginning of which will be in The Massachusetts Review this fall and the end of which can be read here). Details can be found on Facebook, but you don’t have to book your face to attend. Just show up and I’ll read right to you. I promise.

On to the round-up. I got a note on Twitter this morning that the online journal, Instafiction–which, per their site, “provides one quality short story each weekday morning, formatted in a single page, for ease of use with services like Instapaper“–had reposted the excerpt from Mere which ran at The Good Men Project a few months ago. Oddly enough, I also found out that they picked up a short story back in March which I had at the dearly departed > kill author last August. So, thanks, Instafiction. I feel loved. And if not loved, then respected in a way that tells me you want me for my mind.

Which reminds me: the review. In the latest edition of The Critical Flame, Sean Campbell has reviewed The Mere Weight of Words. In it, he made some very fair points about things in the book which don’t necessarily work. But he also caught so many of the book’s subtleties, the book’s pacing/format among them. The movement is meant to imitate memory, not just Mere’s, but her perception of her father’s. Also, Campbell had a great, astute reading of the passage wherein Mere becomes paralyzed:

The best scene in the novella is located at its center. While living and teaching in China, long before her father’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, Meredith awakes to find her face ravished by Bell’s Palsy. Her gradual realization of this is visceral, even frightening. The reader feels her first impressions through this wonderful simile: “My voice was a foreigner: an ugly term, but well-suited to the situation.” It isn’t until much later, when she meets her friend Agatha in America, that the words “Bell’s Palsy” are even used. Instead, we’re left only with her frightened impressions. As she enters a hospital:

“I imagine that the disdain I felt was similar to a xenophobe’s feelings about the non-native’s tongue. Yet my voice’s pronunciation belonged to no ethnic group. Rather, it was beholden to the makeshift, bastardized whims of my stiff jaw and dead lip.”

These arresting metaphors are perfectly allied with the character’s passions: of course a linguist (a phonetician at that) would consider the symptoms through its impact on her voice, her pronunciations, her phonemes. But it also ties in with her relation to her father’s overpowering voice, and in her desire to escape that influence.

On the days when I feel like I’m just writing for myself, when I worry that the scenes which collect in my head will only ever make sense to me, it’s reassuring to get a review like this one.

And now, surely the moment you’ve been patiently anticipating–the random search term which brought someone to my site yesterday: slaughterhouse 5 interpretation of sex scene

Kids, the sex scene is easy–it’s the biggest clue that it’s a fantasy, that Billy’s replacing that which he’d rather not see with that which he wishes were true. But that’s not the scene you need to examine. Look at the death of Billy’s wife, her crazy deathgrin frozen onto her mouth. Why kill her that way? Consider, for a minute, the line wherein Vonnegut reinserts himself into the text after so long an absence (“That was I. That was me. That was the author of this book.”). Interpret his decision to make his presence known at that moment, in that manner. Ask why. Always ask why.