The unapologetic Francis Spufford

By RUPERT SHORTT

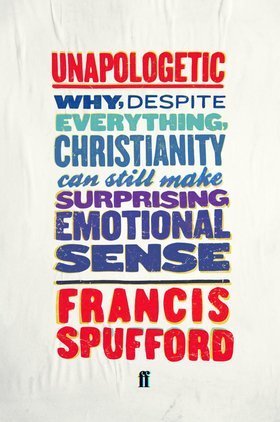

Richard Dawkins’s bestseller The God Delusion (2006) has prompted many pro-religion counterblasts, though none has enjoyed a comparable profile, still less the high priest of atheism’s vast sales figures. Perhaps the situation will change with the publication of Francis Spufford’s Unapologetic, a book written with as much vim and joie de guerre as the works it excoriates.

Spufford, who teaches writing at Goldsmiths College London, knows a thing or two about an arresting opening. “My daughter has just turned six,” he tells us. “Some time over the next year or so, she will discover that her parents are weird. We’re weird because we go to church. This means that as she gets older there’ll be voices telling her what it means, getting louder and louder until by the time she’s a teenager they’ll be shouting right in her ear. It means that we believe in a load of bronze-age absurdities. That we fetishise pain and suffering. That we advocate wishy-washy niceness. That we’re too stupid to understand the irrationality of our creeds. . . That we’re savagely judgemental.” You get the picture.

One function of the rhetorical fireworks is to draw out a point often lost on the forces of militant atheism, namely that religious commitment is a way of life that comes into focus as the believer advances along a spiritual path, not a matter of assenting to 101 incredible propositions before breakfast. Of course a faith such as Christianity makes truth claims, which (among other things) should not be incompatible with modern science. But you don’t think your way into a new way of living: you live your way into a new way of thinking. The emotional and practical elements of faith are indispensable.

Spufford makes a courageous fist of putting his glimpse of the transcendent into words. A pivotal moment came in a cafe one day, when he heard the slow movement of Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto while ruminating on a row with his wife. He describes the music as coming from a world where sorrow is perfectly ordinary, but there is still more to be said. “I had heard [the piece] lots of times, but this time it felt to me like news. It said: everything you fear is true. And yet. And yet. . . The world is wider than you fear it is, wider than the repeating rigmaroles in your mind, and it has this in it, as truly as it contains your unhappiness. . . There is more going on here than you deserve, or don’t deserve.”

He is quick to deny any implied claim that a divine puppet-master was micro-managing his sense of revelation. Mozart created a beautiful and accurate representation of an aspect of reality. And two centuries on, Spufford drew what he sees as a crucial inference from it: “I think that the reason reality is that way – that it is in some ultimate sense merciful as well as being a set of physical processes all running along on their own without hope of appeal, all the way up from quantum mechanics to the relative velocity of galaxies by way of ‘blundering, low and horridly cruel’ biology (Darwin) – is that the universe is sustained by a continual and infinitely patient act of love.”

The clue to Unapologetic lies in the subtitle: Why, despite everything, Christianity can still make surprising emotional sense. The TLS will carry a full-scale review of the book in this week's issue.

Peter Stothard's Blog

- Peter Stothard's profile

- 30 followers