I attended an interrogation course.

A few weeks ago, for research, I attended a law-enforcement course about interviews and interrogations. Several people asked me what happened there.

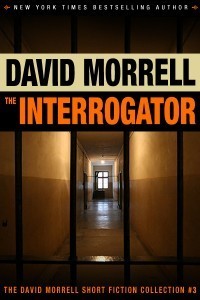

“Interrogation” has violent connotations. We think of people being beaten with rubber hoses etc. in scenes from old gangster films. Or else we think of the water boarding and sensory-deprivation techniques that I describe in my espionage story, “The Interrogator” (available as an e-story with a detailed introduction about my spy training).

But not in American law enforcement. An “interview” is a conversation with someone (a witness, for example) who has information that a police officer needs whereas an “interrogation” is a heightened, persistent conversation with a suspect for the purpose of obtaining a confession.

The idea is to appear to be sympathetic and “to sell that person a prison sentence” our FBI instructor explained. “The best interrogations end when the suspect hugs you out of gratitude because you persuaded the suspect to confess.”

How do you accomplish that? With rapport. When I was a student at the G. Gordon Liddy Academy of Corporate Security years ago, I first learned about neuro-linguistic programming and became fascinated enough that I took an NLP course and became a certified practitioner.

In simple terms, it works like this. People tend to be sight, sound, or touch oriented. Sight-oriented people say things like “I see what you’re getting at.” They look up when they’re remembering something or generating a thought.

Sound-oriented people say things like “I hear you.” They look to the side in the general direction of one ear or another when they’re remembering something or generating a thought.

Touch-oriented people say things like “I don’t feel comfortable with what you’re saying.” They look down toward the floor when they’re remembering something or generating a thought.

People who understand NLP can identify the type of person they’re dealing with and match their vocabulary and body movements in what’s called “mirroring” in order to establish rapport. Think of it in the reverse. If someone keeps using metaphors of sight such as “I don’t see what you’re getting at,” how much rapport will you establish if you reply, “Don’t you hear what I’m saying?” The disjunct is considerable. (Some marriages have been saved by NLP counseling, helping sight-oriented people learn how to get along with sound-oriented spouses. These marriages are literally mixed metaphors.)

The CIA teaches many of its field operatives about NLP because the skill is useful in recruiting and debriefing. Also, a careful observer can even determine whether people are lying on the basis of which way they move their eyes, left or right. Fascinating stuff.

Next time you’re with caring spouses or two good friends, watch the way they unconsciously mirror each other’s movements. One friend crosses her arms. A few seconds later, her friend does the same. Two people are in chairs across from each other. One crosses his legs. Soon the other does. Friends and lovers match each other. A skilled interrogator will study a suspect and begin to mirror that person. Done properly, the suspect doesn’t realize what’s happening, but the effect is to make the suspect feel that he’s been on good terms with the interrogator for a long time. “Do you see what I’m saying?” the suspect asks. “I get the picture,” the interrogator responds, supplying a sight metaphor in response. In a way, it’s like hypnotizing a suspect into confessing.

For several days, this is the sort of material that the instructor explained. I enjoy doing research of this sort and believe readers feel the authenticity when I put details like this in my fiction (again, my e-story ″The Interrogator″ is a good example).

There was one element of violence, however. The instructor showed us a videotape, with the caution that it’s important to be prepared for an interview/interrogation. In the case of the tape we were shown, the officers were far from prepared. They brought in a suspect, put him on a chair in an interview room, and went to get him a bottle of water. Alone, he pulled a pistol from beneath his shirt and blew his brains out.

On camera. Seriously. The officers hadn’t searched him before starting the interrogation. Blood flew out of his mouth. One of his eyes popped out. He slumped. After about fifteen seconds, the gun fell out of his hand. His head sagged. But he remained sitting in the chair. No flying across the room. It ain’t like in the movies. And in this case, it was a reminder that in law enforcement, every conversation, interview, or interrogation has the potential to be deadly.

CLICK HERE FOR MORE INFORMATION