Law Letters posted an entry

For many years I have been hoping for the TV Western to make a comeback, and the deeper I got into my writing career, and watching the market for Westerns fade to a fraction of those glory days, I wondered if it wasn’t a hopeless dream. Thanks to AMC, and their latest endeavor, “Hell on Wheels,” which just started its second season, is on the right track (pardon the pun) to defining the Western for the 21st century.

This is not the first Western series in the past decade or so to start its second season. “The Magnificent Seven,” which started in 1998, ran for three seasons. The controversial HBO series “Deadwood” also ran for three seasons. TNT tried to tone things down a bit with Steven Speilberg’s “Into the West,” which took a fascinating look at the settlement of the American West from the perspective of both the Native American’s and the Anglo settlers, but it aired only one season. From my perspective, it seemed to me that the TV industry was trying too hard to reinvent the wheel when what they needed to do was reinvent the Western for modern audiences.

To understand where I’m coming from you’ll need to acknowledge that TV shows, like movies, are no different than Western novels—they are stories that all require a hungry audience. In his memoir Education of a Wandering Man, Louis L’Amour talked about the market for Westerns in the late 1940s and 1950s, when he wrote for the pulp magazines, being mostly concerned with the action, and less with the characters or even the plot, because from one to the other they were largely the same.

L’Amour was one of the authors that helped build the bridge toward this character driven story, and in the golden age of the TV Western the recurring characters became the draw. We grew to love the Cartwrights, the Barkleys, and Marshal Dillon and Festus. “Bonanza” ran for fifteen seasons, and “Gunsmoke” ran for twenty seasons, the longest running Western TV series ever. And I attribute that to the great writing that wove strong characters and stories together.

L’Amour also had a great deal to do with the incorporation of actual history into the stories. It was more than just a Hollywood studio set when the pilot of “Little House on the Prairie” first aired in 1975 (the year “Gunsmoke” went off the air). Though it still had the TV drama style, historical events and sequencing played a huge part in creating the storyline, which was based strongly on the series of novels from Laura Ingalls Wilder. After nine seasons, ending in 1983, this would be the beginning of the near end of the series Western in the twentieth century.

Where Hollywood failed is in their lack of recognizing the changing trends and the evolution of the Western. We went from action, to character, to historical. But then what? The changes were largely due to the culture of competition for entertainment and delivery, from TV networks to Cable TV and multiple channels. The only successful TV Western in the 1990s was “Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman” which ran for six seasons, and followed the adventures of a female frontier doctor. This may have been largely due to the cinema success of “Dances With Wolves” in 1990, which found unplowed ground playing on the sympathies of the Native Americans, or, in other words, being politically correct. “Dr. Quinn” was not your grandpa’s Western, but more like your grandma’s historical romance.

This plays into the same theory, which goes back to 1969, where some blame the film “Easy Rider” for the fall of the Western. It’s not so much a change in genre preference as it is a change in attitudes, when the youth of that era began to challenge authority and the culture where it was bred. The values of the Greatest Generation were under fire, and even John Wayne spoke publically of how much he despised “Easy Rider” which did nothing more than fan the flames.

We have to remember, too, that John Wayne made a mark on the traditional character Western that will never be duplicated. Louis L’Amour did the same for novels, being a phenomenon in an era that eventually faded away. The great Western novelist Elmer Kelton, whose own novel The Good Old Boys was made into a TV movie on TNT in 1995, also wrote for the pulps, but made a niche for himself writing about less boastful characters and weaving them into actual historical events.

This was all starting to come together for the three of them when John Wayne’s last role in “The Shootist” (1976) was the type of nontraditional character that could easily be seen as the next generation Western archetype. Louis L’Amour, a few years before his passing in 1988, was starting to write a different range of fiction, historical and contemporary, specifically The Walking Drum, The Haunted Mesa, and Last of the Breed.

L’Amour was editing his memoir Education of a Wandering Man when he died, and in that book he spoke of his interest in writing science fiction as well, which was evidence that he was evolving as the audience evolved. Elmer Kelton, who was still writing when he died in 2009, made it very clear that the heroes in his Western stories were average Joes that were not “six-foot-five and bullet proof, but five-foot-eight and nervous,” which were more identifiable by the reader. This follows the theory that the reader was maturing, and the macho types of the previous generations no longer had the same appeal.

If this is true, then what is the next generation of Western story? “The Magnificent Seven” of the late 90s, which was based, of course, on the original 1960 movie, fell short after three seasons. This was an example of what I and many others refer to as the missing ambitions of Hollywood, unwilling to take chances on new turf, yet reinvent what has already been done. The “Deadwood” series may have been a bit ahead of it’s time, then again it’s not network TV, and not something you would want to watch with the whole family. “Into the West” was a terrific series, but it may have been too spaced out, covering too much history in too short of time, to ever succeed as a running series.

The most important discovery was AMC’s Emmy-winning mini-series, “Broken Trail,” in 2006. Here is a perfect example of “unplowed ground.” It was an original, unique storyline, that catered to a mainstream audience. AMC has had a long string of success stories with original series programming, such as “Mad Men,” “Breaking Bad,” and “The Walking Dead,” so naturally it took another stab at a series Western. I had to admit, though, when I first learned of the upcoming “Hell on Wheels” series I was a bit skeptical.

What I did like was how it followed one historical event—the building of the Transcontinental Railroad. I have often wondered why there wasn’t more about this critical piece of history, so it was a good choice. It wasn’t a large span of time, either. It was an event that could easily be spaced out and made to last. My concern, however, was the trite genre references and characterizations, a bow to political correctness, as well as overly macho roles that did nothing for the desires of mainstream audiences.

What we got was the best of both worlds. There is Western action, characters we are drawn to, historical following, and compelling storylines. There is political correctness, but there are also the hard historical realities. There are trite occurrences— the cliché of the confederate soldier coming home to a dead family, the military abuse of Indians, the greedy railroad tycoon, and I don’t know how many times over the years I’ve heard, or read, the Revelation quote, “Behold a pale horse…” For some reason writers think that Bible quote is as iconic to the West as boots and spurs.

Like “Deadwood” there is the modern attraction to the graphic violence, the blood and gore, sexual content, and fairly explicit language. But in “Deadwood” it seemed to be added for superficial reasons rather than something true to the character and situation. In one of the newer episodes, I was a bit surprised when they showed the actual butchering of a hog. Graphic as it was, it was certainly a fair sampling of something one would have encountered in that period and place, and it was certainly not politically correct.

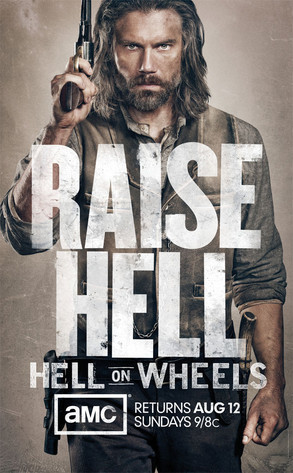

The key lead character, played by Anson Mount, is one of the most rugged original characters I’ve ever seen on TV. He is a product of the times, molded to ride the bloody edges of hell in a corrupt and lawless situation. He is far from friendly, polite, and controlled by his desire for revenge, yet we know that deep inside he searches for peace, even if it’s through death, and despite of how many times he falls.

My next major compliment is the costume and staging. Rarely do you see anyone clean, nor were the streets around them neat and tidy. The mud, and the blood, are a vivid reality. The way they authentically created the tent cities, plank floors, and the commerce that provided the necessities, is to be commended. There is something very real about watching a woman walk across camp in a fancy dress and the edges of her petticoat all muddy.

I also enjoy the dialogue exchanges, among all the characters, which has a nice original, almost modern feel to it, yet mostly correct for the times. The situations among all the people in the camp, from the prostitutes to the Christian crusader, from the immigrant diversity to the racial epithets, have the essence of reality and originality. Along with these things and the compelling storylines, I do believe, all will be the reason it succeeds. Just how long is hard to tell. Regardless, it has my support, and I find myself anxiously awaiting the next episode. That hasn’t happened to me in decades.

P.S. to those of you who have Dish Network, you have my sympathies. :)

Steven Law is the author of Yuma Gold (Berkley, 2011) and The True Father (Goldminds, 2008). Visit his website at www.stevenlaw.com.