A Lynching, an Opera, and a Book

The lynching of ‘Cattle Kate’ is a story most people interested in the history of the west know, yet don’t really know. It’s a story that’s gone through so many permutations, from “Cattle Kate” becoming the name of a western wear company through the all-star, disastrous three and a half hour re-writing of history called “Heaven’s Gate,” that most people nowadays would probably just relegate it to the annals of The Wild West. Basically, the tale as it has stood through the years is that on the morning of July 20, 1889, a vigilante party led by one Albert Bothwell accused Ellen Liddy Watson

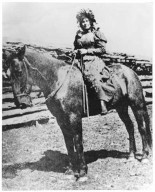

Ellen Liddy Watson, by kind permission of the Wyoming State Archives

and her ‘lover’ James Averell of cattle rustling and branding, and summarily took them out and hung them. Subsequently, Bothwell and his cronies were tried but, being wealthy cattlemen and ranchers, members of the prestigious Wyoming Stockgrowers Association, they were let off. It was left as a shameful episode in the history of Wyoming.

Even as late as 1966, Helen Huntington Smith in her book, The War on Powder River (Univ. of Nebraska Press, Lincoln), was writing from legend rather than fact and calling Watson “ a strumpet with a vocabulary to match.” Huntington Smith was, and is, a respected writer of western lore; her book, We Pointed Them North: the Recollections of E.C. ‘Teddy Blue’ Abbott has gone through numerous printings and is a must-have for any reader of western history. Yet Huntington Smith, while calling the lynching “the most revolting crime in the entire annals of the West,” describes Ella as a “full-bosomed wench” who had “gone west and gone wrong.”

Here is a case of using secondary sources without checking facts. The Cheyenne papers, which Huntington Smith had consulted, were under the thumb of the wealthy ranchers. The stories they had printed regarding this episode were nothing more than yellow journalism at its worst. And the Denver, Chicago and New York papers picked up the sensational stories more or less as written, thereby endowing the account with a prestige and veracity it didn’t deserve. Cheyenne had lifted the soubriquet of ‘Cattle Kate’ from earlier stories regarding a known prostitute who had a reputation as a wild woman who ran a bawdy house and was a known rustler and thief. They pinned the name on Ellen, along with the other woman’s reputation, in order to legitimize the cattle barons’ actions. And that is the way the story stood—until George W. Hufsmith came along.

Hufsmith, who had been born in Nebraska, brought up in Brazil, and gone back to his family’s Wyoming roots to ranch, had studied music and was a part-time composer. He also served for six years in the state’s House of Representatives and was responsible for the formation of both the Wyoming Arts Council and what became the Grand Teton Music Festival in Jackson. To celebrate the country’s Bicentennial, Wyoming commissioned Hufsmith to write its first grand opera—‘The Sweetwater Lynching’—and thereby started Hufsmith on a 15 year journey to uncover the truth about Cattle Kate. The result of his findings became The Wyoming Lynching of Cattle Kate-1889 (High Plains Press, Wyoming).

Hufsmith, who sadly passed away in 2002, did thorough and exhaustive research for fifteen years tracking down records and correspondence and interviewing descendants of the families involved. He discovered that, rather than the hard-bitten cattle rustler and paramour of ‘Cattle Kate’ that legend would have us believe, James Averell was a well-educated former soldier, a postmaster and surveyor and a justice of the peace. Ellen Watson was certainly not a prostitute taking unbranded cattle for her favors, but helped Jim run his store and serve cooked meals. The two were secretly married because the Homestead Act allowed for only one homestead per family. Few couples paid attention to this, and Ella and Jim weren’t an exception; they traveled to Lander to secretly become man and wife, kept it hush, and signed for two homesteads on the Sweetwater. And that led to a problem.

Cattle baron Albert Bothwell had been ranching on the Sweetwater using open range he did not own. When Jim and Ella, combined, applied for homesteads on part of this range, Bothwell lost his water rights. Ella and Jim controlled over a mile of a year-round spring called Horse Creek and, although Jim had sold Bothwell an easement to the Sweetwater, he had also built four miles of irrigation canals. In Wyoming, to this day, water rights mean life or death and cause feuds. Bothwell, an arrogant man full of his own self-importance, was not going to stand for this. And so, on that fateful morning during a round-up, he gathered six of his closest friends, went over to Ella’s homestead and abducted her before continuing on to Averell’s place and forcing him into a wagon. And the couple were lynched.

In Hufsmith’s breezy and, at times, humorous style, he goes on to recount the outlandishness of some of the theories previously put forth. He also shows how witnesses went missing (possibly murdered), how the law was ignored in the case of the six accused, and how history has been hoodwinked by what the press of the day had written. Hufsmith also finishes the story for us: of the six lynch men, four sold up and left Wyoming very soon after being found innocent of the crime. Only Bothwell and his close friend, Tom Sun, stayed on to continue to ranch. In the case of Tom Sun, his family were still there when Hufsmith published the book in 1993. As for Bothwell, he hung on to his ranch on the Sweetwater for twenty-odd years before retiring to California. And then, as legend would have it, he died mad in an institution.

Whatever the truth of the matter, the lynching of Ellen Watson and James Averell proved to be a small battle in a larger war. It was a heinous crime, yes, but it was only the start of what later became the Johnson County War.

**********************************************************************

Nancy Curtis of the esteemed High Plains Press has VERY kindly offered to award one copy of The Wyoming Lynching of Cattle Kate-1889 by George Hufsmith to one lucky reader of this blog who leaves a comment. The winner will be chosen on Sept. 23rd. Or, naturally, you can purchase your won copy here

***********************************************************************

My sincere thanks to the Wyoming State Archives for supplying the above photo, and to Cindy Brown for her help.